‘How’s Southampton Pier’ I asked my father on the phone today. ‘Mostly boarded up.’ he said, ‘and I miss it… I used to enjoy going down there and playing in the penny arcade.’ I presume he meant when he was a child, because I couldn’t imagine him doing that today. Maybe it’s genetic; my son would have done exactly the same – he’s into arcade games, although now they are electronic and rather more sophisticated.

This interest must have skipped a generation because when I was a child I hated them. Like fairgrounds these were grubby places and I didn’t want to touch the machines let alone play on them. I hated everything about a decrepit British seaside town and at top of the list was the scruffy Victorian pier.

In the 1950s a pier visit was a common Sunday afternoon outing and for me it was a bit of a downer – there would be couples promenading along the decking – men in gabardine macs with women at their sides clutching their coats to their throats as the wind tried to blow them into the sea whilst rain threatened from the leaden sky above. Older people too frail to face the conditions sat on seats protected by glazed windbreaks on every side but the front, and dozed or peered out to sea as they waited for a change in the weather so they could get home for their tea.

Once you were at the end of the pier there was the reward of watching a group of fishermen quietly standing with their thick rods lent against the rail. And on the way back those terrible arcades would be rattling away as pennies entered slots, or mechanically flicked ballbearings whizzed around a curved metal track before they ran out of energy and dropped towards a central row of reward slots where they would bounce for a while before dropping again to the gloom of the no win hole. It was so depressing. Most visitors would have paid to get onto the pier and now some machine was eating their money… The long walk back would be wet, windy and miserable. and this was supposed to be fun!

But let’s be fair this was the 1950s – a time when many adults were still traumatised by a war that had ended years earlier; buttoned up with no idea of how to enjoy themselves they came to the pier to break the monotony of everyday life only to discover that their leisure time was no less monotonous than the rest of their existence. The main thing was to keep smiling… to just get out there and make the best of things – above all else you were supposed to stay cheerful in the face of insurmountable dullness. I didn’t know it then, but I was just waiting for the 1960s to arrive, and that didn’t happen in Britain until 1963.

I enjoy looking through old black and white photogaph albums, and usually it isn’t long before you come aross a picture of a pier. Back then they even put piers on postcards – an unintentional warning that at the seaside this was about as interesting as things were going to get?

So, what’s the up side? Well, perhaps we should consider the seaside pier as the most ingenious method that our species has contrived to invade the tidal zone. Maybe you have to think beyond all the fun and just consider these giants as magnificent achievements of heavy engineering – like somebody taking the Eiffel Tower and laying it on its side – then pushing it out to sea – would it make the structure any less extraordinary? O.K. it was a nice try, but I’m not convinced either.

It all started in 1814 when the first pleasure pier opened at Ryde on the Isle of Wight, but promenading wouldn’t reach its heyday for another fifty years when in the mid to late Victorian era piers become fashionable places to walk rather than just somewhere to park a boat in deeper water. Leisure time had just been invented and initially pier activities were a peculiarly British thing. There is nowhere in Britain that is far from the coast; it was as if Victorian engineers felt obliged to do something interesting along the island’s coastline, allowing promenaders to defy reality, caught as they were in this magical world between the land and the sea – try it on a foggy day and you’ll know what I mean. But this notion would wane during the 20th Century as the thrill of walking along a pier became progressively degraded by familiarity, to the point where in the end it became just another trip down the uneven boards to candyfloss-land.

My childhood caught the seedy end of this mundane amusement at around the same time as many of the grand old Victorian structures started falling into the sea. About fifty-five cast iron piers are all that remain standing now and many of these are in poor repair, a far cry from the time when there were more than a hundred such structures dotted around Britain’s coastline, and no seaside town worth its salt was complete without one.

During my childhood I would go with my parents to see summer shows in theatres at the ends of piers, which for a small boy was a pleasantly unsophisticated entertainment. We often visited Bournemouth Pier which was close to home, and this one at least, is still going strong.

Vaudeville though is dead, as are many of the piers that kept it alive. A few have been restored and weathered the storm of social change, but many others have simply rusted away and fallen into the sea. Film director Ken Russell symbolically brought a well publised finale to ‘the end of the pier’ era when Southsea’s South Parade Pier caught fire during the making the rock opera film ‘Tommy’. The blaze could be seen for miles down the coast, and for me this seemed a fitting end to these old fashioned monsters that belonged to a bygone era.

But this was by no means the first time that South Parade Pier has been in flames – it has happened on several occasions – most notably in 1904 when it was completely destroyed and was then rebuilt. Fire is a hazard that has plagued many old piers over the years, and a cynic might suggest that this is another good reason to avoid them.

Graham Green features Brighton Pier in his novel ‘Brighton Rock’: the book is set in the run down seediness of 1930s Brighton, and is very much in line with the way I viewed them during my early childhood in the 1950s. There were once two piers on the front, only one of which remains. Iron, salt water and oxygen are not a good mix unless rust is regarded as a great success and this may be the case for those with an appreciation of patina, but there is a certain point beyond which this appeal is lost to structural engineers, and with this in mind it is little wonder that so may Victorian Piers have been lost to the sea.

Brighton is about 70 miles east of Southampton

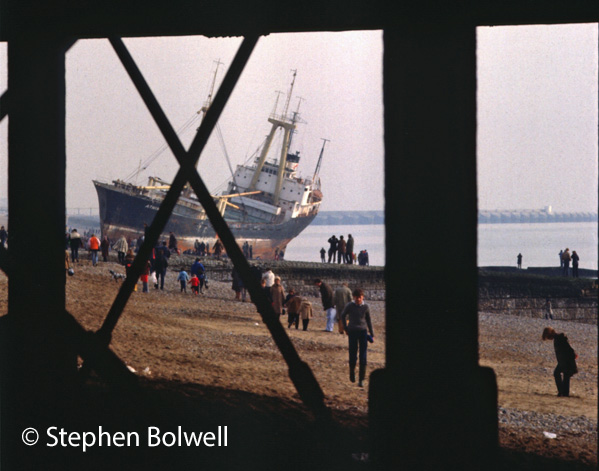

and in 1980 it took about two hours to get there when one Sunday afternoon I drove a girlfriend out along the coastal road to see something that back then passed for an interesting day out. It was the Athina-B, a 3,500 ton merchant ship that had been driven onto the shore by gale force winds. Left high and dry on Brighton’s shingle beach, it narrowly missed taking out the Palace Pier as waves just carried it past during a storm.

When a boat like this ends up on a beach it is impossible to disregard the dangers that can so easily come to the tidal zone. If a vessel this size breaks up and releases oil it would be a disaster, but nothing in comparison to the devastation that might occur if an oil taker did something similar. Considering the number of oil tankers carrying crude oil around the world on the high seas at any one time, it is remarkable how few spills there have been.

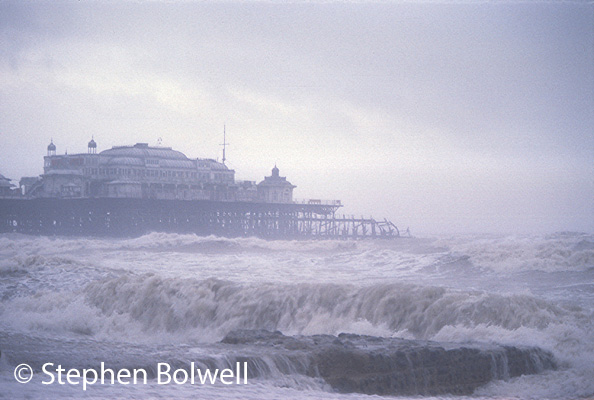

If you’ve ever walked down an old pier during a storm then you’ll have gained a better understanding of the power of the sea, even at low tide this remains the most ferocious strip of the natural world that most of us are ever likely to walk across. Without a pier we simply couldn’t exist in such a place, and that’s great for nature… because with or without a pier, it mostly can.

I recently visited Santa Monica Pier with my wife and daughter, which might seem a world away from Britain’s Victorian piers – in reality as the crow flies it is about one fifth of the world away – and there are surprising similarities. Age for a start; Santa Monica’s is more than a hundred years old and it certainly looks its age, but I prefer it to any of the British piers that I am more familiar with, and this probably has a lot to do with the L.A. climate. People always moan about the weather in the U.K., but really it isn’t so bad until you try walking down a long pier in really bad weather. The other thing is atmosphere and Sanata Monica Pier has that in spades – it is a far cry from anything I remember from the British piers of my youth, and it just seems a far more comfortable place to be amused.

The pier was once just a long narrow Municipal pier that was built in 1909 for the sole purpose of getting sewage out beyond the breakers – there were no amenities to go and see back then, which under the circumstance seems hardly surprising.

The adjoining pleasure pier is the reason most people take a walk down the old wooden boards today and on a Saturday evening things are very busy – there are cafes and other attractions, and the most popular of all is Pacific Park.

It is perhaps surprising to find the pier still standing because over the years it has had to weather more than just the Pacific breakers: threatened during the 1930s by lack of use during the depression it almost went the way of many other failing concerns but managed to survive. Demolition seemed likely on a number of occasions and a couple of major storms during the 1980s, took a terrible toll, but local enthusiasm and funding have enabled essential renovations to keep the old structure going. To an outsider it is unimaginable that Santa Monica could exist without its famous pier.

Nearby, Hollywood has added to the mystique by featuring this old and well loved structure in an ‘awful lot of movies’… or should that be ‘a lot of awful movies’. On balance, the first description is the fairest. In the real world this pier has a laid back west coast charm that you won’t find anywhere else, although when we visited on the evening of the 7th November 2016 a UFO appeared in the sky not long after sunset and almost everybody looked up to see it. Later, we discovered that an unarmed nuclear missile had been tested along the L.A. costline, fired from a navy submarine. What a shame… the story was so much more interesting when there was a chance that E.T. was making a return visit to Hollywood.

It is practical piers that work best for me –

like this one just a stone’s throw from my fathers home in Hythe. The piers main function is to get pedestrians out to deeper water so that they can take a ferry across Southampton Water to the City.

The nearest pier to where I live now is in the city of White Rock on B.C.’s Lower Mainland. The word ‘city’ is stretching it a bit though because this is a pleasant seaside town and one that is easy to find – just head south down the B.C. coastline, and when you find yourself at the U. S border – you’ve gone too far. White Rock is as far south as you can go in Canada if all you want to do is promenade along a traditional old pier – and this one is a good one. The shore doesn’t run out over a classic sandy beach, although there is certainly enough here to build a sandcastle. The tidal region is a bit weedy and that’s fine, but you need to cross a railway line to get onto both the beach and the pier.

The advantage of this pier is that it is a great base from which to observe wildlife:

effectively you can walk across the tidal zone and look down from above as the shoreline changes across its full range.

I have watched salmon pass under White Rock pier as they make for one of the many inlets along the coastline to swim up river and spawn; and I recently tried to get a close-up of a seal – it watched me for a while, then dived and moved parallel to the pier before passing under the structure some 20 metres from where I was standing, so I missed the shot. But sometimes you get lucky and find yourself closer to animals than you might expect; and you are standing on a more stable platform than a boat can provide. A pier is then an ideal place for taking pictures, although you sometimes have to wait for walkers to pass to minimize the bounce of the boardwalk, especially if you are making a long exposure.

When I first arrived in B.C. six years ago I would regularly photograph the many purple ochre stars that lived in the tidal zone – you are not supposed to call them starfish any more, presumably so as not to confuse the sort of person who might think a sea horse could win a race.

When I visited the pier in late 2013 the stars had all gone. I asked several locals if they knew why, but surprisingly few had even noticed their disappearance. Many animal populations fluctuate in cycles that run over several years; usually this is part of a war game played out between predators and their prey, and these strategies can sometimes take millions of years to refine. But the sudden disappearance of the stars seemed rather more ominous and might instead be related to increasing water temperatures, pollution, or a combination of other factors induced by human activity. The truth is nobody really knows, and that’s a real worry.

The disappearance has occured over a wide area, but the sea is a vast interconnected environment and hopefully recolonization will happen at sometime in the near future because population crashes of this kind have happened before – there are however still no purple ochre stars to be seen at the time of posting this article in March 2016.

This disappearance of the purple ochre stars is a good example of how taking a picture can provide precise information about a species before a sudden and unexpected decline. Not many people bother to photograph everything around them on the off chance one image might be useful, but there are enough people taking pictures now, that between us we are unwittingly capturing important changes in the natural world, and if the ‘when’ and ‘where’ are verifiably recorded these pictures could in future provide useful scientific information. Sometimes it is as if we are photographing a crime scene without really knowing that we are doing so – just like photographing the purple ochre stars when I had no idea that they were about to quite literally start falling apart.

Wouldn’t it be great if we threw away our selfie sticks and instead become more engaged with photographing our rapidly changing world. Not everything is about us, and perhaps we should take fewer pictures of our favourite subject and more of what nature has to offer. In future such visual records might in some small way help save the planet, even if most of the time, all we end up with, is an interesting picture of some little creature living at the end of the pier.

You eloquent description reminds me about two piers I used visit as a kid . The first is Cleveland Pier in Somerset. I remember begging my parents to take me there fishing. That’s before it fell into disrepair. After years of fundraising and millions of pounds later I think it has now been repaired and open to the public again. It’s where the Bristol Channel becomes brackish rather than true ocean. I never caught anything but the Victorian architecture reminded me of sepia days long past.

The other was Weymouth Pier with its tacky vaudeville side. It was the year the Beatles released Yellow submarine so it has more of a psychedelic tinge in my mind. I think the needle was stuck on Yellow Submarine, the tune was playing from morning until night. Add the hum of slot and pinball machines and you have the sounds of another bygone era, unless of course you go the Mabletherpe or Skegness in Lincolnshire where time seems to have stood still. Back in Weymouth, mum and dad let me go fishing all day. One night on the way back to the hotel the police running along the beach next to the pier rounding up thirty of forty buck naked hippies who had decided to go skinny dipping. I still the remember the gawking holiday makers tut tutting. It was like a Monty Python sketch.

Great story, it deserves a wider audience, even a film documentary. It sure dredged up some old memories, Thanks

John

Thanks for the comment John, Your memories were just a little later than mine and from the 1960s at a time when I was a teenager and didn’t go near a pier, but I guess as a teenager it might have been more fun visiting them without your parents. Weymouth is certainly a bit more up market than the seaside towns I was thinking of. I remember my wife and I taking my children for a summer visit there when they were small and the beach was teeming with holiday makers. Not long after we were living in New Zealand where if you saw six people on a mile of sandy shore it was a really busy day, and I rather liked that. I intend at some stage to write about beaches and I’ll talk more about such places then. Thanks again, Stephen.