There was a man on the Radio today talking about great crested newts, and that got me listening carefully, because for many years I had an eventful relationship with these fascinating creatures; which might sound odd, but not entirely ridiculous considering that this was the first animal I filmed for prime time television, and the fact that I was suddenly earning a living from what most regarded as a pointless childhood interest at least impressed my father.

My parents were tolerant of my preoccupation with all things amphibian, even allowing me to keep a tank of salamanders in their bedroom – suitable because it was north facing and cool during the summer months; but at the time there was no indication the little creatures that arrived as a gift, would be around for more than 25 years and produce quite so many offspring.

Although I wasn’t obsessive about keeping amphibians, their behaviour fascinated me. My introduction came through a neighbour when I was about eight years old; she worked in a plant nursery and noticed a pond where large numbers of newts were engaged in courtship. She offered to bring some home for me to observe, and I didn’t need to be asked twice, quickly organising an old fish tank to house them, and a regular supply of earthworms to keep them fed.

I couldn’t believe my luck when they arrived – newts are nothing much to look at on land, but as soon as they enter water, their transformation is extraordinary – and I was surprised how much there was to learnt by simply watching them: I noticed for example, that an amorous male would delay coming up for air when he was busy flickering his tail at a potential mate, but if she remained indifferent, he would eventually have to break away and rocket to the surface for a gulp of air, then quickly return before another male could engage her.

At their best amphibians are quite beautiful and they have uncomplicated lifestyles that can be easily analysed – which makes for an entrancing combination. Not so much for my grandfather though who said he wouldn’t visit again until I ditched ‘the dreadful creatures’. Needless to say I didn’t see him again until early summer when the newts had finished their reproductive phase and left the water; they were then transferred to an overgrown part of the garden from where they would eventually find their way to our fish pond each spring to reproduce; and, if the pond still exists, their descendants will still be doing that.

In North America newts are referred to as salamanders, but in Europe the name is restricted to the really colourful ones that dress as court jesters – usually in black and yellow – essentially a warning that say’s ‘Don’t eat me, or l’ll make you vomit’. This colour combination is a worldwide warning displayed by many small animals likely to make a potential lunch for hungry predators: spiders, bees, wasps, beetles and others all make use of this contrasting colour combo, and although many predators don’t see in colour in the same way that we do, it is a defence mechanism that seems to work.

Imagine you’re a peasant living in central Europe long before the internet, television, or even the radio – infact so long ago candles are the latest thing. It’s a cold winter’s night and you throw a log on the fire, and pretty soon, in the flickering light of the rekindled embers, a strange creature walks out onto the hearth. It’s no more than a salamander rudely awoken from a peaceful winter’s slumber, but you don’t know that because science hasn’t been invented yet, or at least it hasn’t where you live – halfway up a mountain somewhere at the back end of Austria. You’re naturally terrified because you still organise your life around the time-honoured habit of superstition, and on seeing the creature, you know you’ve been stricken by a curse. Months later a very old man dies in the village, or perhaps a crop fails… it doesn’t matter… bad things happen because this is the Middle Ages, and everything can be traced back to that fateful encounter with the devil’s fire creature. If only you could have looked it up on the internet, but no… just like my grandfather, you were living in the past and totally ignorant of just how interesting a salamander can be. Today, this rubbery little animal seems far less terrifying, but is still sometimes referred to as a fire salamander.

Britain has only three native species of newt

and none are court jesters. It isn’t so much that newts lack colour, but rather that a great many restrict bright colouration to their bellies. Once again black and yellow or black and orange are colours that might be flashed as a warning and as an opulent display might also be helpful during courtship, but colour can also be a bit of a giveaway, which has led to many species retaining muted upper-sides, to reduce predatory attacks from above.

Sadly, most people dismiss newts as rather boring, probably because they are only noticed when they come to breeding ponds during the spring. Water is necessary during reproduction, but outside of that many will remain land based, hiding away during the day under logs, in crevices, or in the soil, venturing out only on damp nights to feed.

The second species I came into contact with in my childhood was the palmate newt, so named because courting males develop a sooty black webbing between the toes of their hind-feet. Palmates are the smallest of the three British species and I first noticed them in water filled tyre ruts when out picnicking with my parents in the New Forest, where heathland soils provide an acidic environment that the palmates seem well adapted to.

Nerdy information on Identification which some may choose to skip:

during spring, smooth newt males develop a complete crest along the back and tail; palmate males do not, they have a small crest along the tail; but nothing along the back, instead there are two small ridges that run along the upper sides of the body producing a rather boxy shape in cross-section, this in contrast to the rounded curves of smooth newt males and the females of all the other British species. Palmate males have a strong black bar marking running through the eye and a little black pointer that develops at the tip of of the tail. Smooth newts may also have an eye bar, but this is often less pronounced.

The black hind feet and the tail pointer in palmate males makes identification easy, but the females are less easily differentiated from smooth newt females; I remember trying to explain the key differences to an expert just before he was about to give a broadcast on the subject, but for the most part it is a question of experience. The female palmate, just like the male, has a pinkish tinge down the centre of the tail bordered above and below by a darker, often jagged line – but this feature can be very subtle. Outside of the breeding season newts become solitary and maintaining these visual signals is no longer necessary and they become muted or disappear altogether.

The largest of the three British species is the great crested newt,

which has become one of Britain’s most controversial animals; the reason for this relates almost entirely to politics and money, but more about that later. Identifying a great crested from a smooth or palmate is easy – because a mature great crested newt is about twice the size of the other two and reaches about 16 cm in length. The upper body is dark and warty with spots that are darker still – these continue to the orange underside where they make a striking combination. There are sometimes white speckles on the face and along the lower sides of the body, and the male has a white bar that runs along the centre of the tail during courtship and the body crest is clearly serrated – all features that make identification a doddle.

In the mid-1970s the Sunday Times published an article I submitted on the status of great crested newts in Britain. It ended with an informal survey, asking readers to give details of any great crested ponds they knew of in their area.

The response went well beyond expectation – it seemed that great crested newts were more widely distributed than had been previously thought – it really was great crested news! That was until I travelled to look into some of the ponds that readers had mentioned, only to discover that in many cases smooth newts were being misidentified as great crested newts, which seemed impossible to me, if only because of the clear size difference, the warts and the obvious crest serrations that smooth newt males clearly don’t have. Disappointingly, far too many observations were unreliable and I began to think that some people would have had trouble differentiating a big newt from a baby crocodile, and there were a few who would have been pushed to make a reliable I.D. against a hippopotamus. Even today the great crested newt’s status in Britain is in question, which is an unusual situation for a species that many consider to be in need of protection.

Back in the 1970s making a film wasn’t something that many people could afford to do. Between 1974 and 1977 I managed to put together a couple of movies which proved both time consuming and expensive. Today, working on video would have made the process far easier – even a phone can turn out some pretty impressive results, but back then, getting hold of a 16mm film camera (for broadcast quality), and buying filmstock, was a money pit .Half my monthly income was going towards buying just ten minutes of film running time, and it would take several years to shoot a movie devoted entirely to British reptiles and amphibians… How stupid was that? Working on a subject with such limited appeal seemed foolish… but then I got lucky.

The B.B.C. Natural History Unit became involved in a series that David Attenborough had been wanting to make for some time – a television presenter during the 1950s and early 60s, he’d moved into management but now wished to return to the subject that interested him most. The result would emerge in 1979 as ‘Life on Earth’. and it was my good fortune that the series included a film dedicated entirely to amphibians. The producer of the programme, Richard Brock, was brave enough to allow me to film the British amphibians that were to be included, and in the grand scheme of things my contribution would be small, but my sequences would nevertheless involve months of work.

I had been in the right place at the right time and fortunately, the amphibians programme was selected to represent the series for publicity purposes. These cold-blooded animals had turned out to be rather more interesting than most people had thought possibe and the programme won a number of awards, but by that time I was too busy filming other projects to look back, although I fully appreciated that for me, amphibians had been an unlikely but useful start.

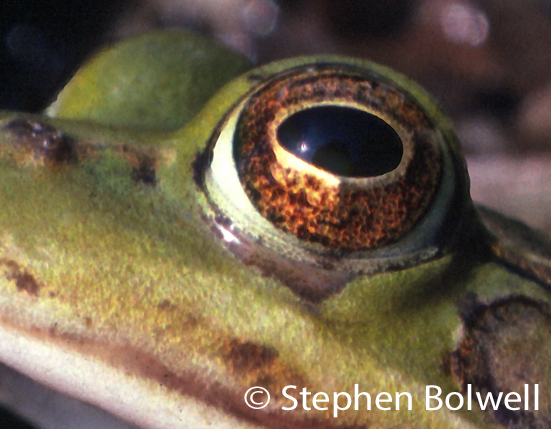

When I first met Richard Brock he told me all about ‘Frogs Law’ a term that had come to signify one of the biggest problems to be faced when filming amphibians – they are essentially unpredictable and usually move only after the camera has stopped runnning; there is not a glimmer in an amphibian eye that will tell you they are going to do something before they do. Animals further up the food chain usually give themselves away somewhere around the eyes, but a frog or salamander will give you nothing, and it isn’t as if they have the flat dead eyes of a shark – quite the opposite – amphibians display some of the most beautiful eyes in the animal world. The truth of the matter is, that if you spend hundreds of hours watching any animal, you eventually learn to pick up on something and run the camera appropriately. Good to know then that all those hours of watching during childhood, weren’t entirely wasted.

Sometimes a male newt displays to a female and she isn’t responsive to his love dance. Perhaps the male doesn’t suit her, or maybe she just isn’t ready, in which case she will usually break away, but often she will just hang around; there is something almost imperceptible about her body language that tells you there is no chance of getting the shot today… maybe tomorrow… and this understanding saves both time and money. Certainly you can’t afford to miss the action, but on the other hand, you can’t watch newts 24 hours a day, because down that road lies only madness.

If you fail to recognise when the female becomes receptive you won’t catch the moment when the male releases his little packet of sperm, after which he will back away still displaying as the female moves forward to pick up the packet on her cloaca. The male knows exactly when to make his release, and if you can’t pre-judge his behaviour and run the camera appropriately, you’re pretty soon looking for another job. And there’s another problem – amphibians respond to chemical signals – pheremones that have been released into the water, but you have only newt body language and the clock to go on – usually when one thing happens, something else will follow. Newts are little reproductive computing machines that with careful observation, are not beyond our understanding.

I filmed my first T.V. newt on 12th February 1977 before filling in the details on a dope sheet wondering if ‘dope’ specifically applied to me – fortunately, it did not. I labelled the roll, ‘Test. Great Crested Newt. Daylight.’ and sent it off to the lab for processing – my wildlife filming career had started.

So, back to the man on the radio – he’s outlining the fact that great crested newts are less common in some parts of Europe than they are in the U.K. and consequently may not require as much protection as they presently receive from European law. For some time great cresteds have been protected under British law, but since the late 1980s they’ve also received an extra layer of care from Brussels due to a policy known as ‘The Habitats Directive’. Under this ruling, 18% of natural habitats in European countries are now under protection. The question is – if Britain opts out of the European Community, will great crested newts suffer because the European Directive no longer applies to them?

I don’t know enough about environmental policy to be certain either way, but clearly the man on the radio was being reasonable. His company built a reservoir, in an area where several ponds had existed that at one time had probably been visited by great crested newts. Under ‘The European Directive’ these ponds had to be monitored, and if great crested newts were found present, these would have to be relocated. The whole process took a couple of years to complete and in the end only 10 great crested newts were found – the conclusion was that the cost of conserving each newt was six thousand five hundred pounds, but the company representative wasn’t making a fuss about that; instead he focused his attention on the newt habitat that had been created and on the whole his attitude was commendable.

There are however issues concerning the relocation of species that are troubling.

Newts aren’t like higher mammals, which might sound obvious, but what is relevant in this case is how their populations are maintained. If only 10 newts are found in a habitat, and say only four of them are females, between them these individuals might lay around 1,200 eggs during a single spring. Certainly predation will take a toll, but amphibian populations often bounce back very quickly – it’s a numbers game; and not withstanding the problems that a reduction in the gene pool may cause, amphibians have a better chance of surviving a decline to very low numbers than do animals with much lower reproduction rates, and so protecting 10 newts as opposed to 10 bears or 10 tigers, may result in a much more successful outcome. The truth is, the success of a species that has suffered massive decline depends to a large extent on what that species is.

In Britain I was fortunate enough to have great crested newts in my garden and know how difficult they are to find. Clearly the best time to move them successfully is when they have returned to the pond during the spring, although this species may remain in the water for extended periods throughout the year. There will however always be immature individuals not yet ready to visit the pond and these are always difficult to locate. Away from water newts are masters of hiding – on occasions I’ve found great cresteds a foot down under soil and one perfectly healthy individual was discovered living five feet down a drain. Even when captive in a tank of moss and soil newts are difficult to find and care must be taken to avoid physical damage when searching them out. In an expansive natural habitat locating every individual is impossible to achieve and the loss of a great many immatures will adversely affect the population in years to come. I know from experience that relocation works, but it should perhaps be regarded as a last resort rather than accepted as a matter of course. As a conservation tool, it is simply better than doing nothing at all.

The presence of a wild animal should on occasions be enough to keep an environment intact and perhaps we shouldn’t move into every location available to us, just because we feel the need to expand – there is a strange arrogance in thinking that the whole planet is there for us to colonies and trash as we please. Great crested newts are just one small part of a complex natural ecosystem and the idea that we should move them or their environment any time that suits us is flawed. Creating habitats for plant and animal populations to expand into can work very well, but moving the complxity of the natural world around like some giant game of musical chairs lacks forethought – ultimately the only species left with a seat might be us and our attendant parasites, thus limiting the sort of games we might be left to play in future.

It may be that great crested newts are not endangered to the point of extinction in Britain, but there can be no arguing that along with their ponds and surrounding habitat this species has been in steady decline for decades.

The common response, ‘It is happening everywhere. What can you do?’ won’t solve the problem, and neither will our expansion into every natural space that is available. It isn’t in our longterm best interest, let alone the many other species we are pushing out as we do so. In many cases we are simply following the money, and then building arguments to justify our actions – ultimately another generation will have to face the consequences, because we did not tread lightly and leave things as we found them.

It is of course ridiculous to think that we can save every newt or salamander from disturbance, but at the very least it makes sense to move beyond the point where we regard protecting other species as a benevolent eccentricity. So, if you uncover something as seemingly insignificant as a newt, or other small creature that you’ve never seen before, then record the time and the place, and always take a photograph to dispel doubt in others. Be proactive – take a picture and maybe in some small way you might help save the planet, even if only by increasing awareness in others.

All the underwater photographs above were taken in tanks using natural light. Please be aware that permits may we required to keep some amphibians in captivity and this should not be attempted without a full understaning of lifestyles requirements.

Dedicated to eight year old Nolan Gagnon who recently donated his birthday money to ‘The Burns Bog Conservation Foundation’. This 3,000 hectare bog is recognised as the largest raised peat bog remaining on the west coast of North America and one of the last major undeveloped natural habitats in lower mainland B.C.. The bog’s survival is down to the persistence and hard work of local people and needless to say, is busy with salamanders and other amphibians which are the key indicators to the health of life on planet Earth.