A Scottish wildlife organisation recently took a picture that might help save the planet – well, the Highlands of Scotland at least. It was on one of those automatic cameras used to monitor animals – and triggered on 17th March 2016 by a Procyon lotor – that’s a raccoon for those of us who don’t have the Latin – standing on it’s hind feet it looked as if it was feeding on some form of bait attached to a post: www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-35942952 The image is technically limited and in contrasty black and white, but there is no doubting this is a raccoon. Baiting certainly works when it comes to attracting raccoons to cameras, but this shouldn’t be possible in the U.K. where they are not supposed to be, and catching one on camera is a real surprise when what you’re really expecting to see is a badger.

Failing a deliberate release, this Highland raccoon must have escaped from captivity, but that’s not exactly an environmental disaster, providing it’s not a pregnant female, or has the opportunity to meet up with a raccoon of the opposite sex… And what are the chances of that? Well, surprisingly good it seems, because a week earlier, on the 11th March, a raccoon was recorded on video just thirty miles away. The same raccoon perhaps? Well possibly, but that’s a bit of a hike for a raccoon in just a week; although when food is in short supply a healthy animal might range that distance, especially if it is a recent roaming escapee that has not yet found a favourable place to set up home. If it turns out there are two raccoons however, this could be the start of a much bigger problem.

I saw my first raccoon as a child – it was perched upon Davey Crockett’s head in a mid 1950s movie that made the most famous backwoodsman of all time a huge box office success in Britain – there was also a popular song that kept ‘The King of the Wild Frontier’ popular for a time – although I’m not sure how long – when you’re small things seem to go on forever. It lasted until the Lone Ranger and Tonto showed up on our T.V. screens to replace him. And surprisingly the Lone Ranger would continue with Crockett’s raccoon theme. More than half a century separated the two characters (and quite bit of fiction); the raccoon hat had been replaced by a white stetson, with the raccoon identity slipping down onto the rangers face in the form of a raccoon mask – this along with an outfit rather too tight for general ‘lone ranging’ comfort, made the character somewhat laughable even to a child. It seemed that back in the old days whether, ‘way down South’ or out there in ‘the wild west’ you were never far from a raccoon, or at least a reference to one, and today this remains pretty much the case right across North America and there is a suggestion that in some states there are more raccoons around today than there were during the 19th Century when fur trapping was hugely consequential.

Raccoons are generalists: if they can find food, they will usually adapt to their surroundings and live almost anywhere. In their native land they avoid only the extreme cold of the frozen north and have managed to become one of the most successful mammals ever to have lived on the continent. In urban situations they have become equally successful, and often considered pests because of their habit of competing with humans.

I must admit, I don’t feel too much competition from the large individual that walks the fence-line around our garden. My family and I live in the Vancouver area of British Columbia where raccoons are commonplace – and not only is this individual a real beauty, it is also one of the largest racoons I have ever seen. Certainly in the northwest racoons can grow to about as big as this species will get. Further south where winters are warmer and summers hotter – in Florida and Mexico for example – a large body mass isn’t so important for retaining body heat and individuals are usually smaller.

Raccoons are mostly active during the night and our local animals will occasionally dig up the garden for grubs, but I don’t mind that. My habit of leaving the garage door open will have to stop though. I accidentally shut a domestic cat into my garage one night when living in the U.K. – the cat wasn’t bothered, and apart from a slight smell of cat the garage was fine, the same thing happened with an owl when living in New Zealand – again no problem – although the cat smell was replaced by a pile of poo under the roost were the bird had chosen to spend the night. All well and good, but if I accidentally shut a raccoon into my garage overnight in Canada, I might just as well opened up the place up to a marauding bear.

I loved the suggestion from a spokesman for the attempted capture of the photogenic Scottish raccoon, that, if it could be achieved without personal risk, it would be great if somebody simply contained the creature in a shed or outbuilding. Now, containing a raccoon is a novel idea – but the last shed I walked through that might adequately ‘contain’ a raccoon was on the island of Alcatraz – maybe Scottish sheds are a cut above the sheds I got used to when living in the South of England as a child; back then you had to turf the wildlife out before you could put the garden tools away; and the door was always left open during the summer months because robins were busy rearing young in an old teapot on a shelf at the back.

A spokesman also said that their organisation had set a humane trap to catch the Highland raccoon… but there had been no sign of it yet, and that’s not a huge surprise. All too frequently raccoons are caught and held by unpleasant limb holding traps, but getting a raccoon secure in an humane alternative isn’t quite so easy: if you don’t capture your raccoon first time around you may not get a second chance – raccoons clearly didn’t spread across a whole continent because they were stupid.

Over the years I’ve photographed, filmed and videod raccoons in many different situations, both captive and wild and there was rarely a moment when they weren’t attempting the impossible.

When filming cheetahs, you can spend days sitting around waiting for them to move, and you’re thinking ‘Just do something interesting… Something I can film… Anything other than just gazing into the far distance!’. Then after a couple of days they will get up and go for a mobile lunch and you can hardly keep up, even in a Land Rover. Raccoons on the other hand are the exact opposite, when they are awake, they never stop moving – sure they rest up, but if a raccoon isn’t hidden away having a kip, it will usually be ambling along doing something interesting, and providing you aren’t hassling the creature, you can usually keep pace on foot.

A raccoon is an inquisitive creature – brighter than a rat, a cat, or a dog, they have a never say die attitude that provides an easy fit for those who think they’re a little bit like us… and in some ways, perhaps they are. It doesn’t make sense zoologically, but it’s fun to think of the raccoon species as evolving along a different route to create a creature that ostensibly does things the way we do, but without the advantage of starting from a primate.

Their little paws are superficially hand-like and with great sensitivity can manipulate objects – in particular food, and their alert little brains will get them into just about everything, which helps them survive in all manner of circumstances. It all sounds familiar – especially the little brains!… We can anthropomorphise them to our hearts content and that’s certainly the reason they make such good cartoon characters… we relate to them, and their little bandit masks in particular trigger our imaginations. They appear to us as devilish little bandits behaving without restraint, which is exactly the mindset of any raccoon worth its salt – as anybody who has ever tried to keep one will tell you.

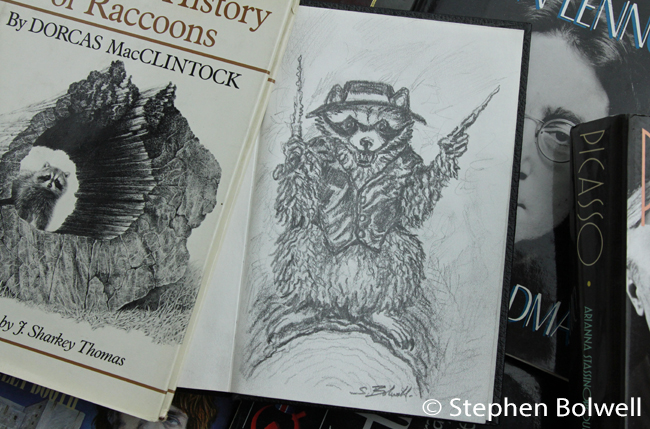

If you’re thinking that keeping a raccoon should be on your bucket list… forget it! It takes a very forgiving nature to become a raccoon’s best buddy. There are however people – like Dorcas MacClintock, who have managed to do so successfully, and on numerous occasions. In the mid-1980s Dorcas became my mentor in all things raccoon related; somehow she managed to bridge the gap between art and science; as both an award winning sculptor, and a respected mammalogist she had moved beyond the simplistic recording and analysis of racoons as living organisms to see the bigger picture. Dorcas also has a sense of humour which is not only helpful, but an absolute necessity when dealing with raccoons. David Niven once said of his friend Errol Flynn, that you always knew where you were with Flynn because he would always let you down – and that’s more or less the way it is with raccoons – you can’t just turn your back and expect them to sit quietly – they’re going to get into mischief.

Dorcas taught me how best to understand what a raccoon will do next, which is essential when trying to film them. I learnt how to second guess their behaviour and anything Dorcas had forgotten to tell me, she had already written down in a book which she gave me. I learnt for example that you don’t try to stop raccoons from doing just about anything they want, instead you divert their attention with something more interesting and usually, that something is food.

The truth is, I usually leave the captive raccoon diverting to somebody else because it’s a full time job and I just do my best to record the action. Working with a wild raccoon is pretty much the same – you grab what you can, because if a raccoon is doing anything, it’s most definitely worth running the camera.

With a racoon in the wild there is no doubting that the setting is natural, but with a captive animal, which parts of the process touch base with reality? Well, whatever a raccoon does is his or her own reality… because they will never do anything that they don’t want to, or anything that doesn’t come naturally. So, if the intention is to demonstrate some aspect of behaviour, I don’t think filming a captive raccoon is a major deceit, but if you are supposedly telling the life story of a wild animal and filming most of it on a set, essentially what you have is a soap opera, which is fine, but of no particular interest to me.

The thing about filming natural activity is that unless you plan to make a twelve hour nature film, there has to be some editing, and I’m more worried about that than many other aspects of the process. One very good reason for editing your own material is that there is a better chance of telling the truth, simply because you were there. The alternative and often preferential route is to put a story together from bits and pieces filmed over a period of time, and some professional film makers might say that it will be a dull story if it isn’t done in this way. Which might be the case, but I think it far more interesting and informative to watch things the way they really happened. There is however compromise to any edit – it might be necessary for example to drop a close up in to move the action along, and so keeping the flow authentic is a constant challenge.

The viewer is always in the hands of the movie-maker, who has the option to tell it as it is, or alternatively, make a story up, and to a point there is always a degree of manipulation. Secondly, nature isn’t simply about getting bloody in tooth and and claw – animals attacking has become fashionable on both television and the internet, but watching animals going about their daily lives demonstrates that there is a lot more going on. Just as with us, everyday activities may not be quite as exciting as a battle, but raccoons tend to do things with more gusto than most and their behaviour is often comic, a combination that will always provide cinematographic value.

This YouTube of a raccoon dabbling is captivating, but clearly not of a captive animal – without edits the action retains a feeling of authenticity. You might not want to watch the same behaviour for an hour, but a short clip like this is absorbing, and you learn something about the habits of a wild animal: raccoon dabbling. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W0lI3ub3DI8

Whether in captivity or in the wild raccoons appear delighted to have something to do – it is simply in their nature. Out in the wild, much of what they attempt seems destructive to us, but really they are just making a living much the same as we do when going about our business, except that we trash quite a bit more of the environment than they do in the process. I understand why many people view them as a nuisance, nevertheless it is ironic that as we start to move into their world they have a habit of pushing back, and at some level, you have to admire that.

In all honesty, if you take a picture of a raccoon in its native country you probably won’t contribute very much to saving the planet, but if you live outside of North America and get a shot of one in the wild, it might prove very important to conservation. Certainly if this species takes off in Britain – a place where raccoons really don’t belong – they would undoubtedly compete with native species that are already under pressure and their presence create environmental havoc. If a raccoon really did think and behave exactly the way that we do, he’d probably be saying ‘ Nice one… Bring it On!’ But in truth, Rocky is just doing what all raccoons naturally do… and he doesn’t have an opinion one way or the other.