For most of my life I lived close by the New Forest in Hampshire and have always considered it special, because although busy with visitors during summer, it has remained an important haven for wildlife as the surrounding countryside has steadily urbanised.

The New Forest looks natural, but in reality it is heavily managed, and with increasing pressures from both inside and out, some say that it is no longer the place that it once was – but people have been saying that for generations. A more considered analysis suggests, that it is just a question of how far back you want to go before you start moaning about what you think has changed.

In many ways this is a notoriously conservative area, stuck architecturally somewhere between the Middle Ages and the early 20th Century. The Forest certainly isn’t noted for its modern energy saving buildings and panoramic views across the heath, because few such places exist.

There has been very little movement beyond Edwardian times, apart that is, from the traffic – almost everything else appears to have stalled around 1910, and ‘being there’ sometimes feels more like a museum or theme park experience than any modern reality… and this is unlikely to change now that the New Forest has become a National Park because Britain’s National Parks seem habitually locked into some imaginary idyl of the past. But then that’s essentially what us Brits do best – don’t you know? We look back fondly and say, ‘things were better back then’ – which of course is little more than delightful delusion.

I once considered buying a house in the Forest, but was put off by the crumbling mud wall of an outbuilding that had to remain exactly as it was for historical reasons, along with a rusting tin roof that on no account could be replaced by something more appropriate; such exacting attention to detail can only have heighten my appreciation that the Forest is at least genuinely old.

A Brief History of The New Forest.

In the past the Forest was often referred to as ‘a furzey waste’ (meaning gorse covered) a term that goes back well before 1079 – the year the New Forest was designated a royal hunting ground, primarily to provide Norman kings with somewhere to pursue and kill deer which appears to have been their favoured leisure activity. Having fun was often unsophisticated and violent; and back then, the notion of ‘fun’ didn’t feature in many people’s lives. If for example you were a peasant trying to make a meagre living off of the Forest, and got caught killing a deer to feed your family, the penalty could be the loss of a hand, and in a worse case scenario, an unpleasant hanging.

Even kings didn’t have it all their own way. On 22nd of August 1100 King William (Rufus) – the son of William Conqueror – was hit in the chest by an arrow and killed outright. There is a stone to commemorate the event, although even the briefest of research indicates that this was no more than an 18th Century vanity project, and the original site remains to this day, uncertain.

So, a peasant called Purkis slung the king’s body onto a cart and transported it to nearby Winchester – those were the days! The Normans reigned through a time when history was really happening in the area, much of it of their own making. To have a king shot more or less on your doorstep must have been quite something, but when all the excitement died down, the Forest subsided back into its usual state of Snoozeville and nothing much else happened over the centuries until the arrival of the M27. However, if you had been a biologist back at the time when the New Forest was founded (admittedly long before biologists existed) and could magically have lived for a thousand years, you’d certainly have noticed a great many changes in the formation of the landscape we see today.

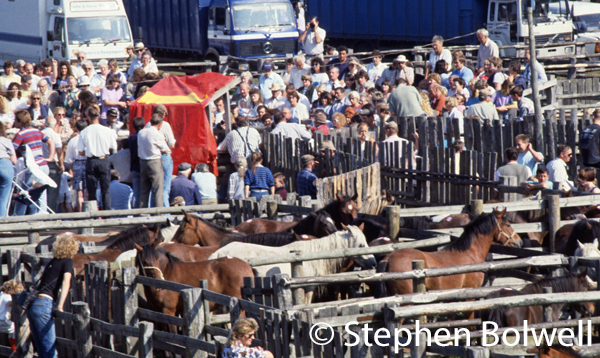

When I was a child this agreeable place was crown-land managed by the Forestry Commission and that’s the way things would remain until 1st March 2005 when the Forest transitioned into the smallest National Park in the country, a status initially unpopular with many locals, but under different management livestock grazing became a priority (not that it was’t a major consideration before); this would be of great benefit to the commoners (the locals who live here) who for centuries have exercised their right to graze stock on the open forest.

When kings began to find more interesting things to do than take pot shots at deer, forestry quickly became the key activity and the woodlands would soon provide an important source of timber – in particular the provision of oak trees for the building of naval ships. Enclosure (usually referred to as Inclosure) of wooded areas to protect trees from grazers, started under the reign of Elizabeth I, a procedure that became more rigorous during the 1700s and was further refined as time passed. Over the years there have been periods when trees have been the priority and periods when they have not – and the same might also be said of the grazing of livestock and the management of deer.

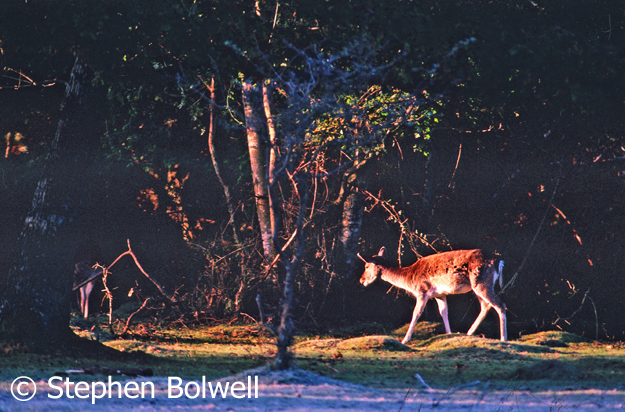

In the early 1850s there was an attempt to get rid of the deer altogether with the passing of ‘The Deer Removal Act’ – no doubt the Norman kings must have been turning in their graves; but clearly the policy didn’t achieve its longterm aim, although it did herald the modern period of silviculture that the Forestry Commission has carried through to the present day.

Clearly The Forest has seen a rollercoaster of changes, but from our modern viewpoint of rapid economic growth, this interesting mix of woodland, heaths and open lawns seems to have hardly changed at all, and from a layman’s point of view it is an ancient place that has been standing still for centuries.

There have always been many different opinions as to how the New Forest should be run and the resulting issues are wide ranging: is there too much grazing or too little (sadly, I’ve never witnessed too little!). Other considerations include commoners rights, shooting, horse riding, bike trails, heather management (burn it or cut it, and then how frequently), deer culling, tourism, nature conservation… the list goes on; and with so many interested parties, co-ordinating management is a nightmare, especially when the pressures on the Forest are ever increasing.

In total, the New Forest covers about 25 square miles, and considering all that is expected of it, this is is not a very extensive area. Its borders now end abruptly, which wasn’t the case when I was a child. Rapid urbanisation and population growth to the east and west have squeezed it, and this is one of the reasons the New Forest is now such an important recreational area. Add to this how accessible the Forest has become in the last fifty years. The M27 (developed during the 1970s) ripped through its heart as devastatingly as the arrow that ripped through Rufus, with its ‘straight as an arrow’ functionality in stark contrast to the narrow backroads that meander through other regions of the Forest, many of which haven’t changed for years.

Changes.

I returned for a visit the New Forest a few weeks ago; living as I do on the west coast of North America I haven’t spent much time in the area since leaving Britain in 2002, which has been rather useful, because it is easier to notice changes that I might otherwise have missed had I continued to wander the Forest on a daily basis.

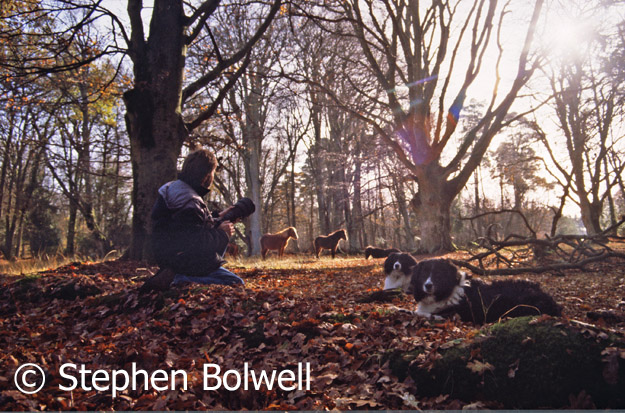

Prior to leaving Britain I was frequently out there filming wildlife films for television, along with videos of the area. Sometimes I would just wander through for pleasure, but I rarely did so without a camera, which over the years has resulted in the taking of thousands of photographs, in particular during the last quarter of the 20th Century – this period became the subject of a book – but more importantly it is pictures that have provided a reliable method of making comparisons of change.

Since my childhood I’ve observed visitor numbers steadily rise on the open forest, and this is especially noticeable during holiday periods, but in general I’ve avoided photographing this aspect of life – even I am locked into my own interpretation of how the Forest should be – essentially devoid of people. People will occasionally get in the way of a decent photograph, but few wander very far from the car parks and their presence is easy to ignore, although of course there is a bigger picture to consider – one that involves increasing pressures upon the landscape.

So, is it an increase in visitor numbers that has caused the Forest to become so blighted by litter? The very first scene I filmed for the B.B.C was a seemingly timeless view across a pond, but when I viewed the result, there was a Coke can bobbing in the lower left hand corner of the frame which meant I had to go back and film the scene again. This was embarrassing, because even an exceptional liar would find it difficult to deny the presence of something once it has been recorded on film or video; but the fact is, having litter in your frame of view was a far less common event back in the mid-1970s than it is today.

I never made this mistake again, and since then, havealways carefully checked the frame of view before making a picture. Increasing New Forest litter isn’t then a matter of opinion, or a false memory of better times; it is a judgement that can be empirically measured by the time it takes to clean up before going all happy snappy with the camera. Thirty years ago, clearing up litter before taking a photograph wasn’t a prime consideration… and now it is.

On the 29th April 2016 I parked my car in a New Forest car park ignoring the obvious litter in the immediate vicinity and walked along the roadside noting the spread of rubbish to as far as about five metres from the carriageway. There was clearly no shortage of the stuff, but it dropped off as I moved towards the heathland, which suggested that most of it was flung from moving cars, but even at a distance way past the range of an Olympic javelin thrower there was still plenty of rubbish to be found strewn across the open heath.

One of the reasons that I wanted to leave Britain was litter, because it was almost impossible to ignore, as was the response of foul language and abuse that I usually received when I politely asked people to pick up what they had discarded – this most noticeably from children… which was depressing.

When my family and I moved to New Zealand in 2002, one of the best things about the change was that litter was less a feature of the N.Z. landscape than it was in Britain, and you might reasonably consider this to be down to a lower population… but it was more than that; in New Zealand there was a different attitude – people were actively searching out bins to put their rubbish in, and throwing rubbish onto the ground didn’t come naturally to that many people. The one time I did ask a child to pick up his discarded rubbish when walking along a street in the small town of Te Awamutu he did so at once, if rather sheepishly, and then apologised – which really stuck in my mind because this had never happened before. Living on the opposite side of the world away from what I considered a cultured society, I suddenly discover that what I might initially have considered to be the back end of nowhere was altogether more civilized than what I had become used to in Britain, and this was a real culture shock.

I’ve lived in Canada now for about six years, and it would be crazy to suggest that Canadians don’t litter, but they don’t do it to anything like the degree that some people do in the U.K.. The writer and humorist David Sedaris has written and talked about littering in Britain and believes heavy fines would make a difference. By his own admission Mr Sedaris is disturbed by this oddly British problem, and some might say he is a little obsessive judging by the amount of time he is prepared to spend picking it up. He is a native of the U.S.A. but has lived elsewhere and travelled extensively – he clearly knows what he is talking about and Britain is lucky to have him.

When I lived in the U.K. I used to walk to the letterbox at the end of the road and I’d pick up all the litter on one side of the road going down and pick up the rest on the opposite side coming back. My neighbours thought I was barking mad, but to me it just seemed the responsible thing to do. If I was now living close to the Forest I’d take a bin liner out with me once a week and pick up as much as I could during my walk.

Fining people isn’t going to solve the problem in out of the way places where they are unlikely to be watched . Littering is a mind set in Britain and many won’t readily change their behaviour with good grace, and so sadly, it falls to the rest of us to clean up if local authorities are not going to do it, because littering will only get worse if we decline to rise to the challenge.

When I was regularly using the New Forest as a subject for my photographs I had no trouble clearing up litter when I saw it – and I don’t think it unreasonable to suggest that if you walk your dog on the Forest then you should consider doing the same. Anybody who walks on the open forest regularly should be prepared to occasionally take a bag out and pick stuff up.

There are people who expect to find a bin wherever they go – even in the natural world – and when they don’t, they find it acceptable to discard their rubbish wherever they are. I have no idea what must be going through their pea sized brains… but I suspect very little.

The discarding of rubbish when the bins run out isn’t a problem restricted entirely to Britain. I am presently in Mexico photographing parrots in what I consider a remote place, but of course it isn’t remote to the locals who live here. Today I’ve walked along a gravel road and it is this which allows easy access by vehicle to a swimming hole on a river that runs parallel to it and it is close to there that I am taking pictures.

Rather than take their litter home, people are steadily adding to the pile – its very presence seems to have validated this as a place to dump. The rubbish might at some stage be cleared by a local authority, but in the meantime it will take only one windy day to redistribute this junk into the river and surrounding forest and that is depressing, because in every other respects this is paradise.

I hate to be critical of Mexico because it is such a wonderful place, but it does have a litter problem, although of course I’m selecting by recent experience. The truth is, that with just a few exceptions, littering is a worldwide problem.

It seems that no matter where we are, when the bins run out, so does our restraint. To see piles of rubbish elsewhere in the world certainly puts the New Forest problem into perspective, but the pertinent question remains, in a place where there is no shortage of wealth and education… should we be seeing litter there at all?