Overgrazing the New Forest – a major contribution to species decline.

I wrote recently about ‘The New Forest’ and the obvious truth that it has a litter problem, but there is something more consequential going on that has been bothering me for years – the fabric of the Forest is being eaten away by herbivores more quickly than it can regenerate, and rather like the litter – there is no sign of a change for the better.

The New Forest, for those who don’t already know, is a patchwork of habitats ranging from lawns, through open heathlands to forests and all are maintained by grazing. This has been achieved through the centuries by giving local people the ‘right’ to graze livestock on the open Forest and those entitled to exercise their ‘common rights’ are known as ‘commoners’.

The look that is achieved with this approach to management isn’t exactly wild, but neither does it feel agricultural – it’s somewhere in between and usually happens in areas where the soil is too poor to support more intensive forms of agriculture. If such places were left to their own ends they would eventually return to the wild.

The British have always had an uncomfortable relationship with wilderness, we pretend to like it, but in truth we can’t seem to leave the natural world alone. Every available space, especially common land has to be useful and any environment that hasn’t already been utilised is just begging to be grazed, rather than allowing them to return to overgrown wastelands – the terror of it! The New Forest is no exception; in ancient times it was often described as a furzey waste. The prevailing view is, that if we can’t make use of such places, then they are no use at all.

The idea that every bit of land has to be owned by somebody, or at the very least has to be useful in some way is ingrained in us – it’s almost a religion. We believe it because our predecessors believed it – a process that has gone on for generations, with nobody stopping to ask: would the natural world really be such a bad place if we just left it alone? Sadly, this is an errant thought because it’s never going to happen, particularly in the New Forest where local people see grazing livestock as their birthright. So, what exactly does that leave us with?

Apparently something that’s not half bad; semi-natural habitats maintained by the munching of farm animals which benefits a variety of plant and animal species when it is done right. Ponies, cattle and in some places sheep – these in very low numbers, wander the open Forest all year round. And during autumn, pigs are turned out to feast on fallen acorns that ponies would otherwise fill up on and poison themselves – they are a bit stupid like that. Pigs on the other hand seem able to convert almost anything into bacon.

The big question is: how much grazing does the Forest need to maintain healthy eco-systems and when does it become too much? Even to an untrained eye the New Forest is presently going through a prolonged phase of overgrazing – and with all of the other pressures that now exist – probably one of the worst that has occurred during its long history.

In 2010 Natural England designated 16 million pounds to encourage the ancient right of commoning, essentially to promote grazing. In April 2016 under a partly European funded Verderers’ Grazing Scheme the pot was increased to 19 million pounds which allowed a per annum payout for each animal of around 85 pounds for cattle and just short of 70 pounds for each pony. A recent EU-funded ‘Basic Payment Scheme’ was introduced to help farmers in general, which might entitle commoners to a payment just short of 250 pounds for each of their cattle and 269 pounds for each pony, with no cap on the number of animals for which payments can be made. Essentially this has become a licence to print money for anybody living in the Forest exercising their grazing rights, which is an extrordinary deal considering that the land being utilised doesn’t belong to those who are putting stock out. So, everybody and his auntie must have joined in by now because it’s a no-brainer. I don’t know of any commoners who would be ostentatious enough to wallpaper their bedrooms with fifty pound notes, but many will have at least taken the opportunity to update their four wheel drives.

Promoting grazing with financial incentives seemed like a good idea around about the time the New Forest became a National Park, because this was a period when putting animals onto the open forest no longer appeared to be giving a good return and for many commoners didn’t seem to be worth the effort; stock numbers were beginning to fall, and with few exceptions wildlife was starting to benefit – because creating the right level of grazing is a difficult balance, but a drop in numbers was clearly proving to be good for the environment. Sadly, there was only a short respite. Throughout my lifetime the trend has been for stock numbers to increase, with pony numbers more than doubling in the last half century to around 5,000 and cattle numbers also increasing significantly in recent years.

Now that grazing is back with a vengeance the New Forest is looking increasingly like a badly worn pitch and putt – or should that be ‘a badly worn crazy golf course’! – because the traditional furzey waste that has existed for centuries is now in rapid decline.

The intention was, “to attract new, younger commoners to continue the traditions that have contributed to the rich biodiversity of the forest”, perhaps this quote should have stopped at “to continue the traditions” because there are no grounds for suggesting that this is contributing to the rich biodivesity of the Forest. The good news continues with, “to preserve the rich beauty of these acres” which might be nearer the truth because beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and that takes on a whole new meaning when money is involved. What would really benefit the Forest is for control to be wrestled from the traditionalists and placed in the hands of those who have a better understanding of the ecology of existing habitats.

Most would agree that the open Forest requires grazing because this is a process that creates not only the look of the place but also very specific environments that are seldom seen elsewhere. Overgrazing on the other hand can cause considerable damage and that is the present situation.

There are a handful of wild plants that benefit from a heavy grazing regime, but there are many others that provide food and cover for butterflies and other animals, that are being grazed out of existence. A diversity of plants is necessary for the maintenance of well balanced ecosystems, but this diversity is now being lost – and that’s not an extreme opinion, it’s a matter of fact.

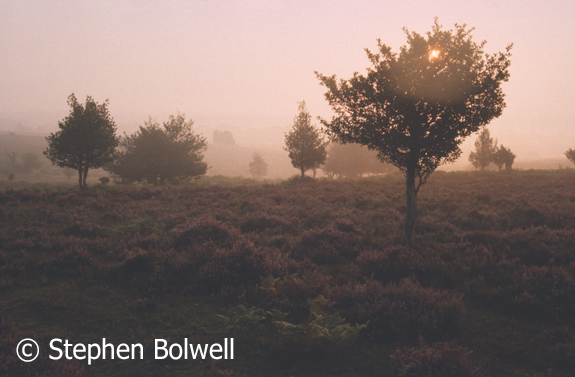

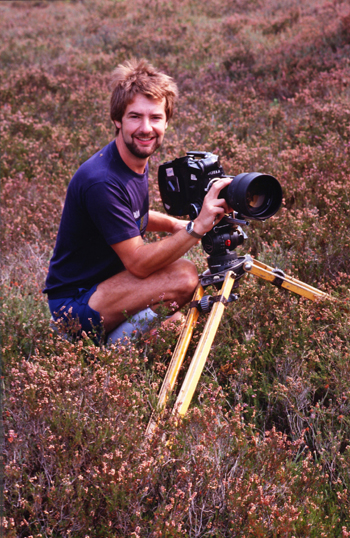

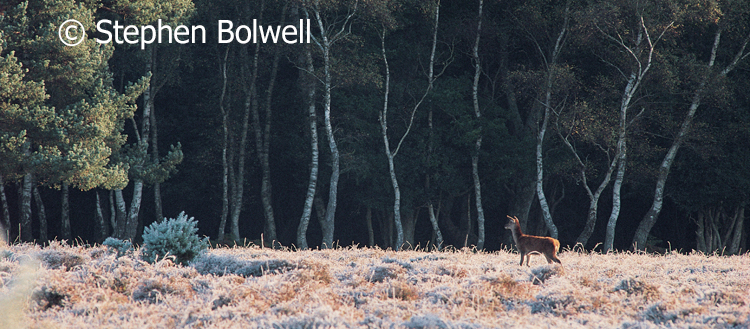

Over the years I’ve spent many thousands of hours observing the New Forest through a camera and have gained some understanding of the ecology, as well as the distribution and behaviour of many of the animals that live there. But it doesn’t matter what I think I know about the place, it is the changes recorded by photography – particularly during the last quarter of the 20th Century, that provides evidence beyond dispute, demonstrating a general degradation of the environment directly linked to overgrazing.

Many say that the New Forest hasn’t changed much over the years, but if you go away for fifteen years and then come back as I have done recently, you certainly notice a difference.

But let’s go back further…

This is a fun picture, but it is here for another reason… as a record of the surrounding habitat as it once was. Behind all the splashing a band of gorse and heather can be clearly seen at one end of the pond.

Compare this to a picture taken in 2016 two months short of a twenty-four year period, this time looking in the opposite direction across the pond.

The reason the place looks so barren is entirely down to the impact of large numbers of herbivores – in this case ponies and cattle – and it isn’t just the munching of fresh growth that has caused the problem, it is also down to trampling, in particular of the heather.

I don’t think anybody can say exactly how many stock animals now graze the Forest, but the steady increase over the years is at odds with maintaining balanced ecosystems. Perhaps as many as 170 species have been lost from the New Forest since I started taking pictures in the late 1960s and there can be no doubt that some have disappeared as a direct result of heavy grazing.

This isn’t to say that ponies and cattle don’t play an important role in managing New Forest ecosystems, just that there are now far too many animals for effective conservation to operate. The question is, why has this been allowed to happen? Some will say that the payment of subsidies and a mis-guided management is to blame, but these are topics that are off limits for discussion.

There have always been deep seated attitudes in favour of grazing which has become the ‘Holy Grail’ of New Forest management – not because it is best for the environment, but because it is ‘a way of life’ for the commoners who live there, and their ‘rights’ always take precedence; and this is something that is unlikely to change.

A common sense approach would be to manage optimally to benefit New Forest ecosystems, using grazing as one of the many tools available to achieve this end rather than as an end in itself. The pretence is that this is already happening — nothing could be further from the truth… but I’m old enough to realise that arguments based upon facts and logic don’t always win the day.

Behind the pond in the above picture is an area of heathland that has, for as long as I can remember, been a good environment for the small and very beautiful silver-studded blue butterfly, an extremely localised species usually confined to heathlands that have been managed to maintain short heather. This can be achieved by controlled burning, a strategy that is not popular with all conservationists because it is so indiscriminate, but done at the correct time of year may be less damaging than an accidental fire during late summer when a burn can go deep into a dry peaty surface, resulting in a recovery time of many years. Whatever the case, the 2016 pictures demonstrate that this heathland has burned recently which should provide nourishment to an otherwise poor soil and aid in the regeneration of heather, but this clearly isn’t happening here.

This habitat is no longer maintained the way it was from the 1970s through to the new Millennium, a period when I filmed the silver-studded blue on many occasions. This heathland environment has changed substantially in recent years and not for the better; today it has almost no heather in places where it once grew profusely and is beginning to turn into a lawn.

Another argument for maintaining areas of short heather is that a handful of plant species do very well under a closely cropped grazing regime – usually small plants that are easily overwhelmed by other more robust species. However, it is common to find these mini-botanical wonders in other places where the heather is older and denser; along the edges of well trodden pathways for example, which provides a trampled habitat appropriate for their survival.

There are clearly areas where plants that are specialists of short heathland can survive without resorting to heavy grazing. Despite this I am not trying to make a case against putting livestock out altogether – I appreciate that they are an effective means of managing open Forest environments but essentially it is a matter of degree. The process should not be used simply as an excuse to graze stock without due consideration for the Forest as a whole. Sadly, the degradation I have outlined on a heathland I am familiar with can now be seen across much of the open Forest.

The present heavy grazing regime inevitably leads to the formation of lawn areas which the New Forest has no shortage of. Fewer grazers would lead to more balanced habitats with greater variations in heather maturity and the regeneration of many other plant species that have been eaten out.

The situation is depressing, because back in the 1960s and 70s environmentalists were already moaning about grazing pressures, and it is difficult to fathom how it is possible for things to have become so much worse. It certainly isn’t true that the Forest can’t survive without ‘commoners’ exercising their grazing rights to the present level, although in some quarters it is controversial to even hint that there is a problem.

An argument that the New Forest pony might become extinct if numbers were reduced is a ridiculous proposition. The possibility that the breed might disappear was far more likely during the Victorian era when efforts were made to improve the ponies by adding new blood – a procedure that very nearly turned the New Forest pony into a completely different animal.

When I was filming on the Forest during the 1990s, there was a concern, that at auction, ponies were less likely to find their way to good homes in this country, and far more likely to end up on the dinner tables of the French; this was accompanied by concerns about how humane it was to transport the poor creatures alive across the English Channel for slaughter in Europe.

It should be remembered, that although some of us are sentimental about New Forest ponies and concerned for their welfare, there are others for whom they are just a business.

The reality is that there’s no longer a need to ride around on a pony as for a century or more most of us have been using alternative transport. Riding a pony can be a pleasant activity, but few now wish to live in a mythological version of the Middle Ages, although on the Forest there are still those who cherish the idea, just as long as the present grazing subsidies remain intact.

Any rational person might consider that lowering the present level of livestock grazing on the New Forest is fundamental to the conservation of species diversity in what is without doubt a unique combination of habitats; but despite evidence to the contrary, there is enormous opposition to any reduction of grazers and the unhindered continuance of what has become an environmentally unsound ‘right’.

Now is the time for a more balanced view and this needs to come from an independent source, in particular from people whose judgement is not clouded by the lure of subsidies and who essentially can more clearly differentiate a ‘right’ from a ‘wrong.

With thanks to Jen for being the inside of a New Forest pony and the New Forest Visitors Centre for loaning the outside.

Next: The Overgrazing of Streamsides and Woodlands.

As we enjoyed the New Forest so often during our 10 years in Southampton I found this a sad essay to read. Enjoyed your photographs , which lead me to think what a vast archive you must hold.

Thanks Linda. Sadly there’s another to follow on the subject. Yes, I have every picture I’ve ever taken, apart from the ones that went off to publishers and were damaged or lost… It wasn’t long before I stopped sending them! I have an even bigger library of 16mm film and when I’m gone there is probably going to be a really big and environmentally unfriendly bonfire. All the best, Stephen.

How refreshing to see your article setting out what is really going on in the New Forest.Lord Manners, the Official Verderer as reported in the Lymington Advertiser and Times yesterday views the Forest” as not overgrazed at present”. This despite articles in the same paper in 2015 and 2016 headed ” Commoners warned over rising animal numbers” (2015) and”Concern over big increases in commoners’ animals in the Forest” (2016). The previous Chief Verderer had warned in 2016 that increasing stock numbers “could lead to overgrazing,food shortages and welfare problems for animals”.

I have been doing some research on this issue as we have in my Parish of Ellingham,Harbridge and Ibsley a planning application for two commomoners’houses,barns and stables on the HCC owned land at Rockford Farm :as a parish councillor I am not allowed to say any more until after the planning meeting on Tuesday.

However,I have walked the adjoining Rockford Common and was shocked at what I found ;the only good thing was that I heard a woodlark singing away in a birch tree.

I have lived here close to the National Trust Commons since 1951 and it is very sad to see their present state ; heather is stunted or dying in places,some firebreaks are used for riding of horses and the heather plants have neen all but destroyed, gorse is barely regenerating, the silver studded blue are reduced in numbers. The hare is no longer seen the Dartford Warbler which survived on Ibsley Common after the 1962/63 winter is rarely seen. The clump of New Forest Gladiolus on Ibsley Common was wiped out in order to provide more grazing and some of the bracken has been sprayed with chemicals to leave a barren wasteland .

What I find amazing is that there is no control over the walking of dogs in the bird nesting season ,even though the Forest and commons are classed as open space land

Thank you for your comment Patrick. I am puzzled that more people aren’t as concerned about the general state of ‘the New Forest’as they should be. The decline you have been noticing has been going on for some time now and got a real move on after the area was designated a National Park, which ought to a surprise to us all. This general decline has continued throughout my lifetime, and I am certain, for a longtime before that (having spoken to people who lived in the area during the 1930s). I think that most people don’t notice the steady changes, or question so much when a diverse environment steadily moves over to pasture – even though the soil type is not entirely up to making a success of that. There’s still greenery and ponies with no new houses going up, and all importantly, somewhere to walk the dog; for many people this suggests that things are O.K.. However, anybody who has an understanding of the natural world and claims the Forest to be fine and not especially overgrazed, must be either deliberately choosing not to notice, or one step short of perambulating with the walking dead.

I have just been informed of a conference on Commoning called “New Forest Knowledge ” to be held morning and afternoon on 29th October 2018 with those speaking including Tony Hockley of the CDA , Lindsay Stride and Clive Chatters but no one as far as I know due to talk on the excessive number of stock in the New Forest and over grazing.

During the hot very dry Summer just gone , most cattle were off the Forest being fed hay , as the only grazing was in the valley mires or under trees .Large areas of heather seemed to be scorched and dying , as too some gorse and birch leaves turned brown on a number of trees .

I hopefully will give the web site for the conference below :-

https://nfknowledge.org/2018/07/24/commoning-conference-29-oct-2018

Thanks Patrick. I am not surprised that people involved in the process don’t really wants to talk about the overgrazing – there appear to be rather too many deaf ears on the subject. It is remarkable the situation has attracted so little attention as it is impossible not to notice that the problem has increased dramatically in recent years. Thank you again for the details.

Chris Packham is scheduled to have an article on BBCI , Inside Out at 7.30pm on Monday next week on possible overgrazing in the New Forest

Chris has been very good about speaking up on this problem, but it is quite difficult to comment on such things from within the Forest where there is so much opposition to upsetting this gravy boat of subsidised grazing. I have recently seen books and articles about various improvements – such as increasing the bogland areas by re-instating the original water courses in some areas, but very little about the problems caused by overgrazing. It has become a barren wasteland of lawn, with no cover along streams, and fewer plants to benefit species such as butterflies and moths – there is very little regeneration of any plant that needs to grow more than a couple of centimetres out of the ground before it flowers. So, hopefully this isn’t considered a ‘possible problem’, but rather a very real and present threat to biodiverstity.

We have had a number of incidents of attacks by cows in our Parish of Elingham , Harbridge and Ibsley in recent weeks .

Early Spring was on the dry side and grazing must have been limited for the number of cattle turned out . I have seen cattle grazing on common sorrel which is growing in profusion over several acress ever since the National Trust wiped out bracken with herbicides .

I am wondering whether some of the cows may have calcium deficiency through eating too much of the sorrel ; one of the symptons of this deficiency is excitability.

Another factor is that some of the cattle turned out are not Forest animals and need much more feed than is available in the New Forest .

Hello Patrick, What you have to say is interesting. I know only that sorrel is beneficial to humans when eaten in small amounts, but excessive consumption can be hazardous; and I understand that when livestock eat too much of it they may suffer from a Calcium deficiency and exhibit symptoms similar to milk fever. I must say linking sorrel to the behaviour of cattle would never have occurred to me until you mentioned it and unfortunately I don’t have the expertise to comment further.

The problem isn’t limited to the New Forest I am afraid and it doesn’t surprise me that national park status has made the situation worse. George Monbiot has been writing about this issue for year. Parks have an appalling record when it comes to eco-system management and wildlife in general.

Not helped by the vested interests in the conservation sector. Once an idea gets into their head, good luck trying to change it. Much of the UK conservation sector is militantly anti-tree. Which is understandable with conifer plantations but seems to extend to all trees, even the native ones.

In the Ashdown forest woodlands have recovered from an historically low level to cover 40% of the site. Which would be welcomed in most countries but not here. The management plan sets woodland extent to 40% of the site, my guess is because they know they can’t risk the mass tree fellings that they actually want.

I understand that heathland is a valuable habitat, though research shows that heathland mixed with woodland and scrubland cover is a better habitat. What bothers me is the extremist view of many of the conservation lobby who wish to create bare featureless moonscapes and pretend they are good for wildlife. With every tree felled and everything grazed flat.

What conservationists do in this country is often little better than gardening, to make things look tidy.

I think the issue is also historical. Britain appears to be locked into the past; even architecture has been set into certain preferential periods from other times which must be maintained at all cost, as if it were a priority to avoid any sign of the here and now; this is the way theme parks operate, conjuring up imaginary glimpses of happier times. Almost always the take on the selected past is sentimental and often quite inaccurate. In some places the official line is that there really is no present or future, and the landscape appears similarly locked in. The Lake District looks the way it did according to the Lakeland poets; and Wessex is still viewed through the eyes of Thomas Hardy. Unfortunately these re-imagined historical periods of preference rarely put the natural world first. The trend at the moment is to maintain traditional rural practices, which sounds fine, but the process is often detrimental to nature – and more often than not, there’s an awful lot of grazing involved – it is as if the landscape cannot survive unless there are sheep. In so many places rural Britain is locked into sentimental imaginary idylls that might just have existed far away and long ago – often with the help of substantial subsidies from the here and now – as is the case with the New Forest – which on receiving National Park status made it a priority to support the medieval idea that locals should be encouraged to turn out their stock animals to graze… and somebody else should pay for it, which wasn’t really the way it worked when things started back in 1217: in consequence the forest has become seriously overgrazed, making this one of the most likely reasons why the area has experienced such a rapid decline in species diversity in recent years.

An excellent article I have been living on the edge of the forest for over 20 years the decline due to over grazing is clear. I wrote this letter to the local press today.150 Everton Road

Hordle

SO410HB

Sir

With the combined scrutiny of the Verderers, New Forest District Council, The Forestry Commission and the National Parks authority we should feel that the New Forest is In safe hands. We often hear through the press and other media of the issues of excessive dog poo, rogue off road cyclists and fly tipping to name but a few. We are made very aware of how these illegal activities, if not kerbed, will have a negative impact on the forest and it is rightly important that steps to restrict and prevent them are taken up by the bodies whose role it is to protect this unique environment.

Why is it then that whole areas of the Forest are currently being devastated by what I understand is a perfectly legal activity? Which of the bodies are responsible for allowing indiscriminate, large scale erosion of paths and grazing pasture by allowing too many livestock out so early on to the Forest? In the last week a herd of in excess of 60 cattle have been turned out on to the Forest in the Wooton Yew tree Bottom area. The ground is completely waterlogged, the grass has barely begun to grow and as they maraud around looking for limited food, they are just destroying long established paths and the very areas of potential pasture that they, the ponies and deer need to survive.

Another aspect of their arrival is the traffic chaos as they move quickly down the roads frantically looking for access to the non-existent food. I have just witnessed (Thursday 20th Feb. 5-00pm) a complete roadblock of the traffic at the junction just to the East of Wooton Bridge. I witnessed several frustrated drivers bump the cattle with their vehicles.

There was media coverage last year of the increased numbers of cattle put out to grazing and the negative impact on the Forest. It appears that is happening even earlier this year. I am not a farmer, but I understand that no Farmer would put their cattle out to graze on their own pasture if it was waterlogged as it could damage it irreparably. Why is this ‘farmer’ allowed to profit from causing potential long-term damage to a national asset as important as the New Forest? Who is responsible for controlling this apparent legal activity, someone must do so before it is too late?

Yours sincerely

Eric Freeman

Hordle

Sorry to be late on this Eric. I am afraid I didn’t pick it up quickly enough. Please accept my apology.