The patch of forest I’m about to take pictures in is about an hours drive south of Puerto Vallarta on the west coast of Mexico in the Bay of Banderas.

Selecting a site to take nature pictures isn’t always easy, especially in tropical and sub-tropical forests where lush plant growth limits the chances of a clear view; there is nothing quite so infuriating as hearing a bird close by and not being able to see it. The second problem with dense leaf cover is the limitation on light, which can inhibit making good exposures adding yet another layer of complexity to working in the woods.

It is now only about three and a half hours before my wife and I will take a taxi to the airport and reluctantly fly out of Mexico, which means I need to optimise my chances of getting a handful of wildife pictures in the limited time available, and this is how I’ve chosen to do it.

I’m walking to a site that is approximately half an hour from our hotel, which is a little further out from the ones that most tourists stay in, centred as they are on the main beach resorts which don’t usually have such ready access into the forest as the one we are staying in.

It is now after 10.00 a.m., but I’m not overly concerned by a late start because an overnight rainstorm has continued into the morning, and earlier, the light was poor. The suggestion that you have to be up and out before the crack of dawn to see wildlife is a myth as it very much depends on where you are and what you are hoping to see.

In flat open places getting out early makes sense; the light can be dramatic and provide more interesting photos, but in forest, there is sometimes an advantage to moving out a little later; you may not see as many birds as you would have earlier in the day, but then you probably wouldn’t have had enough light to photograph them anyway. All is not lost by waiting until after breakfast when sun dependent species such as reptiles and butterflies are usually more frequently seen, and I’m hoping to photograph some of these today before heading back to eat, shower and make our pre 4.00 p.m. departure time.

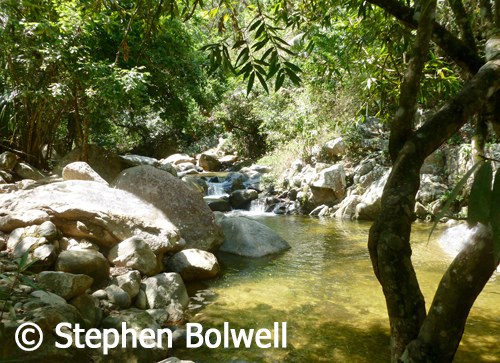

I follow a dirt road along the river, heading into the hills and stop close by a swimming hole, where the forest opens out. There is seldom anybody here before mid-day during the week, and at the edge of the forest good light is available. The river is only about 20 meteres down a rocky slope – this proximity to water ups the species count and overnight rain has freshened everything up.

Because time is limited I will remain in one place, moving no more than 20 metres in any direction and for most of the time I’ll be standing still, hoping to photograph anything that passes through. Looking up into the canopy visibility is limited and this combined with my self imposed range esentially confines any activity to an approximate 20 cubic metres.

This is secondary forest and sometimes what appears to be natural… isn’t. There is a well established mango tree close by, but this isn’t a species native to Mexico. Mango arrived during the early 19th Century by a circuitous route from its native land of South Asia, and the ancestors of this tree probably started out in Burma or eastern India.

For several hundred years it has been difficult to guarantee that what you see in a forest really belongs there because we have a tendancy to transport plants with agreeable fruits from one place to another, and we move many other plants that can be utilised for other purposes e.g. trees for timber and rubber plants for rubber, along with a wide range of plants that we just find visually pleasing.

A great many species have been moved to where we think they will grow best and a lot have colonised their new surroundings as successful plants tend to do. I’d prefer to photograph a native animal feeding on a native tree, but if an interesting bird shows up and starts ripping into the fruit above me, I won’t be ignoring it.

I have visited this location three times over the past week, and have a fair idea of what shows up. Yesterday evening I noticed some fruit had been dropping – a ripening that can be attractive to many birds and insects – one fallen fruit has been cleanly sliced, possibly by a beak, and I suspect parrots have been feeding here recently. There is very little sign of bird droppings, but as the fruit is only just ripening, visits may have only just started. Where rivers cut through the forest we’ve seen noisey flocks of parrots flying along the corridors they create, but I’ve not yet managed to photograph any birds, and it is perhaps a little hopeful to think that I might do so in the limited time left to me, but nevertheless, it is one of the reasons I’ve returned to this spot.

In most cases standing in one place on the off chance that something might pass through is a waste of time – waiting requires logic and reasoning, unless of course you think this is going to be your lucky day; with a limited number of heartbeats available to each of us it is perhaps better to make decisions based on observation rather than gamble time away.

Ripe fruit and seeds are powerful attractors, but to photograph nectar feeders and pollinators it is necessary to seek out flowers.

It is not essential to know what species they are – anything with bright colours is good, although many insects utilize ultra-violet and don’t see colours the way we do.

A strong scent is another indication that flowers are attempting to attract pollinators and there is nothing to be gained by waiting beside a plant that is wind pollinated – such flowers can be plentiful but are often small with muted colours, however very few wind-pollinated plants will show up in the lower section of a forest where still conditions make the process impractictical.

There is no magic to being in the right place at the right time; the signs are usually obvious; it is just a question of clocking up the plus points to optimise the chances of seeing an interesting animal. Careful observation also opens up the opportunity of learning something new, and in tropical forests there’s a real chance of photographing a species that hasn’t been recorded before.

In a previous post I mentioned that Mexico has a litter problem, but for the most part I’ll conveniently ignore the rubbish pile that is increasing by the day about 10 metres to my right in what in all other respects is paradise. Instead, I’ll do what I’ve done so often before when filming wildlife – point the camera in a direction of whatever accentuates the positive and minimises the negative. Positivity is generally highly regarded – our brains like that sort of thing – but there is a time and a place for everything, and if we continue to ignore the terrible state of many natural environments, we must do so at our peril: our negligence has now reached epidemic proportions. T.V. wildilfe documentaries in particular continue to lull us into a false sense of security – buoying us up on a tide of beautiful pictures, until we pretty much believe that everything is going to be alright, when the truth is… it really isn’t.

Whether this edge of the forest will remain intact for another ten years is open to question because development for tourism is rampant and almost everything is up for grabs if the money is right.

When taking photographs I am often a lone Englishman amongst local people. Presently, there are very few tourists around because it is the start of the rainy season – a discouraging period for sun seekers, but there are also those too frightened to come out of the resorts into Mexico proper because news reports back home suggest that they might be kidnapped and held for ransom. In most out of the way places here nothing could be further from the truth. Mexicans are a friendly and courteous people and it is safer walking out in this location than it is in many parts of the U.K.. You might feel especially safe visiting the Isle of Wight in the South of England, but if you cross Southampton water and wander along the sea wall in the old town of Portsmouth on a hot summers afternoon when the local lads have been drinking it might be another story. And then of course there’s Syria…Everything is relative.

A couple of days ago, I saw and photgraphed a pair of basilisk lizards basking on rocks only a few feet from where I am presently standing, the sun was intense and I didn’t manage any really good pictures, so I’m on the look out for the lizards again. There was one here yesterday evening sat on a rock in the river and he did a really good job of avoiding having his picture taken.

Today, there is a sizeable iguana close by the rock where the baselisks were playing at statues a couple of days ago and is keeping a warey eye on me. I get close enough for a picture on the 400 mm without causing any disturbance and get lucky with some fairly even light – I wait for a cloud to partially obscure the sun – the exposure still looks like a full sun exposure but really it isn’t – the contrast has just dropped enough not to blast out the highlights on the rock (our brains are better at compensating for extremes of light than a camera and so we make images in photography work to fit that, and this situation might encourage some to even things out by using flash, but I never do that, although I will admit to sometimes bouncing light back onto a subject using a reflector, but not today – this is as near to our brains reality as a photograph can get.

There are now several butterflies taking turns to sit out on twigs and leaves right infront of me – they do so one at a time, until a sitter takes flight to interact with another flying over and then returns to land indicating that these are probably territorial males. I take loads of pictures, few of which are any good as these butterflies don’t remain in place for very long. I’m never going to capture a shot of an individual with its wings open, as might have been possible earlier in the day (so much for a late start being no problem!). It is now well over a hundred degrees F and all sit with their wings closed, orientating to minimise their surface areas to the sun which aids in the regulation of their body temperatures.

While I’ve been absorbed in butterfly behaviour a bird I’ve never seen before lands on a branch straight ahead of me and it would be difficult not to have noticed the flash of lemon that signals the upfront arrival of this bird. Usually I am careful to move slowly so as not to frighten a twitchy bird and sometimes it is a toss up between not missing the shot and not moving too fast, but I know by this birds confident posture that it isn’t likely to leave anytime soon; it moves its head from side to side, holds each pose for a time to provide full opportunity for a variety of shots, and I begin to wonder if it has shown up with the expectation of being fed.

Then I hear the parrots, a large flock have just crashed into the tree above me and I know they are feeding on the fruit, because all sorts of stuff is dropping out of the tree. Their noise is raucous and continuous as they bash about in the upper branches, but I can’t see a single bird – it’s very frustrating. I move about a little in order to get a view of at least one, but the leaf cover is dense and I see absolutely nothing. After a few minutes the flock moves forward into an adjacent tree and now I get a glimpse of this tumbling sprawl of birds, with one group flying a few feet and then landing, followed by another, then another, until the first group moves forwards again… and so on.

I move with them fearing that they will keep going beyond my range, but then I get lucky, they land and settle in a tree – the forest looks natural but for some reason a wire fence runs down between me and the tree ending about 25 metres before the river leaving a walkway through at the top of the rocks wide enough for me to walk through with the gear. The parrots are now settled and preening and are going to be there for some time – if they hadn’t moved I’d have shot everything within 10 cubic metres, but they’ve doubled my range. I’m ducking this way and that trying to get a clear view of one or other of the preening groups. I settle on three that are squashed close together and watch as one or other offers a head for a group head preen; now the one in the centre is swinging under the bough and nibbling at another’s claw – the other two are engaged in preening themselves and frequently bury their heads so deeply ito their wing feathers that they appear headless – it is difficult enough getting shots through the branches, without two of the birds appearing decapitate for 80% of the time.

Add to this the lack of light and my rapid uprating of the ASA and I am dubious about the grain on the pictures I am taking, but there are now several groups of birds partially clear of the foliage, and so I just keep taking pictures until I run out of memory on my card and then replace it with one which is also part filled and soon I have to take a third card from another camera in order to keep going, I know I should take some flash pictures but resist the temptation. I don’t have a top of the range camera, and it can be slow and I don’t want to have wait for it to load up as well as recharge for the flash. I just keep taking pictures as quickly as I can -other than being in the right place, there is no skill required to do any of this.

I once rescued a parrot from a pet shop that looked a bit like these, although his head and wing markings were slightly different. Wally was, I think, a white-fronted Amazon, but he probably never saw the river because most likely he was captive bred. This was a bird pining for his owner – an older gentleman who had recently died; he wasn’t eating and pretty soon he would become ‘a late parrot’; so, for a time I took him everywhere with me, even allowing him to sit on my shoulder as I drove the car… don’t try that though, it’s probably illegal and certainly a distraction to other drivers. Slowly Wally came out of his depression and began eating again; once he was feeling better it was as if he’d suddenly remembered that he was at the centre of the Universe. Key words would set him off and he’d start raucously screaching a repeat of things you said whilst bobbing about madly; when you laughed, he laughed. It was cyclical hilarity and often became hysterical. Then one day he met my father and it was love at first sight, he would do little dances turning this way and that, and then flash his wings to impress him… and soon they moved in together and Wally would become very bad tempered when they were seperated – perhaps my father reminded him of his previous owner. I don’t advocate keeping parrots, but completely understand why people want to do it.

I see another pair of parrots in good light and start taking shots of them… then a single parrot is wandering about in even better light and grab a picture as he walks along a branch.

The parrots hang around for about twenty minutes before they start moving on. The three break up and then there are two, now too far apart to frame together comfortably. I take this as a sign to give up and get on back down the road to eat by the pool with my wife and take a shower while she organises a taxi which she manages before I’ve cleared the room of luggage. Once again it’s about heartbeats and we aren’t wasting any of them.

Within the hour we are in an air-conditioned airport which seems a million miles from the green encompassing humidity of the morning where wringing wet I could hardly see for the salt in my eyes as I strained my head back and I manoeuvred my tripod to keep a small group of parrots in frame. Parrots that were completely indifferent to my presence, and if it weren’t for the pictures I’d be tempted to think I’d simply dreamt the whole thing up. It was fabulous. There is something agreeable about not being part of it – I was there, but for all the difference it made, it was as if I hadn’t been there at all. In twenty years time it might be interesting to return and see how much of paradise remains, by then it might be neck deep in litter or a hotel complex with the name ‘The orange-fronted Parakeet’ although of course there will be no sign of anything resembling a parrot apart from a relief picture on the wall because ironically, we have a habit of destroying the very things that we think we care most about.

With thanks to Dr Mathew Cock for confirming the identification of my butterfly pictures.