I was out in the garden yesterday

trying to convince plants to grow when I was buzzed by a drone – an exceedingly stealthy one. I didn’t see it, but certainly I heard it, hovering behind my head before making off at speed.

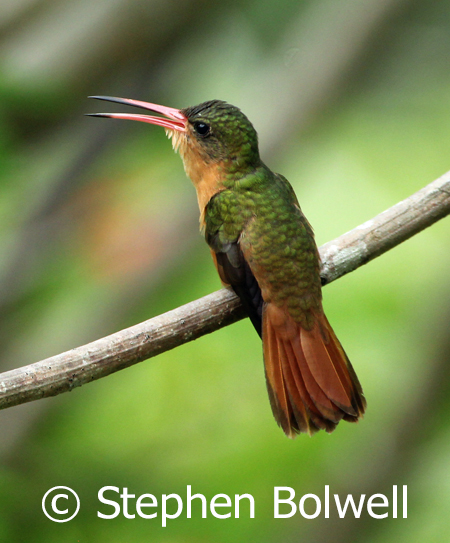

My wife sitting in a nearby lounger was able to make a more realistic observation – I was standing on the flight path of a rufous hummingbird, a creature weighing no more than a spoonful of sugar… it was attempting to visit a bee balm flower. Not quite a drone then, but even the most technically advanced machinery can’t come close to the manouvreability of a hummingbird – this the only bird that can fly backwards due to some fairly unique muscle structures that control the wings… wings that can quickly carry them from a standing start to a top speed of 30 m.p.h.. Right now the brain of a tiny bird easily outstrips anything human technology can achieve, but who knows, maybe one day?

The odd thing about rufous hummingbirds is just how noisy they can be as they fly past you, their wing feathers thrumming loudly as air rushes through them and usually the first indication that the birds are around. They can also be quite vociferous with their repetitive vocal clicking – usually directed at other birds but also sometimes at me, when I’m standing in the wrong place!

My most recent hummingbird encounter is one of many; thinking back to earlier wildlife filming trips when I first started coming out to the Americas, there was hardly a visit when I didn’t see one. Living as I now do in the Vancouver area doesn’t provide a huge hummingbird species count, but I’m just happy to be seeing them right through the year. If I had to make a list of my favourite things, only Africa would get a higher rating, and yes, I do get how odd it is to make a comparison between a large continent and a small bird.

Hummingbirds are a New World species that most likely originated in South America; these ever resourceful birds can now be found as far north as central Alaska, and as far south as the tip of Tierra del Fuego.

When my family and I first arrived in Canada we had only a balcony to attract wildlife and so we put up a bird feeder – a big cedar provided an agreeable background which like so many trees in Canadian gardens was attempting to take over the whole plot. My bird photography was going well, then one day to my surprise a hummingbird showed up and started licking at the peanuts and we responded by putting a hummingbird feeder in place. Soon after a family of Anna’s hummingbirds were regular visitors – there was an adult male, a female and three youngsters… each sibling completely intolerant of the others, aggressively buzzing their brothers or sisters whenever they started to feed. They seemed to have a real attitude problem, but that’s a very human response – all they are really doing is ‘grabbing’ at their best chance of survival.

The next year, I’m guessing it was the same pair of adults that showed up again and things went much the same way as they had done the previous year. The fall came and the rufous hummingbirds I had seen feeding in the park moved on, but I left the feeder out for stragglers… and then something interesting happened, the Anna’s hummingbird just kept coming and continued to do so right through the winter and this surprised me.

This never got old –

you’d be washing up on another desperately miserable day, and this beautiful bird would suddenly appear and hover just a few feet infront of your face – eliciting a feel good factor much appreciated in the middle of winter – these seemingly delicate creatures just the other side of a kitchen window in conditions that a human would not so easily deal with if they gave up on the chores and walked out of the back door.

Early one frosty morning I noticed a hummingbird working the nectar feeder at a really odd angle, and I soon realized that it was cold enough (at about -7ºC) for the sugar water in the container to freeze and make feeding a problem. From then on I would check every morning before doing anything else and thaw out the enegy drink whenever it was necessary. We were soon to move house and my first thought was that we couldn’t leave during the winter because the local hummingbirds had become reliant on the high energy food we were providing.

Our winter feeding Anna’s hummingbirds would get a jump start on potential nesting sites when they moved further north the following spring, and some might travel as far north as Alaska – a neighbour told me that it was proven that hummingbirds hitch a ride on the backs of geese, although I’m not quite sure which nursery rhyme she got that one from!

Living on the Edge.

It was a surprise to see hummingbirds waiting out winter in difficult conditions at the back of our house and I began to wonder how these little birds managed to survive so many cold nights when it was clear their feathers provided very little insulation.

The answer to this question sounds more like science fiction than science fact: each cold night the birds endure a near death experience; an evolutionary adaptation of their metabolic system which provides them with an extreme solution to an almost insurmountable problem.

They are able to survive falling temperatures by going into a form of suspended animation which parallels the Zuni claim that hummingbirds can slow down time. For the birds it is as if life is standing still; their existence hanging on a thread as they become hypothermic and go into torpor, with body temperatures dropping well below their active daytime body temperatures which are usually maintained at over 100˚ F.

After a cold night, it takes a while for hummingbirds to come back from the dead, and they do so by vibrating muscles in a similar manner to a moth or bumblebee generating heat before taking off from a cold start. Then it’s a race to find food; there are no lazy hummingbirds, individuals get busy as soon as their flight muscles will allow and quickly begin searching for food just to stay alive.

Small warm blooded animals have a large surface area in relation to their body mass, which means they lose heat far more quickly than do larger animals; in consequence hummingbirds are continually seeking out food, living fast food lifestyles without the downside of obesity.

Hummingbirds are exceptional in many ways:

they can achieve the highest heartbeat of any animal when fully active – at about 500 beats per second; and have the ability to convert sugar into energy far more quickly than any other warm blooded animal with adaptations to the digestive system that allow for rapid absorption of liquid sugars. The gizzard/stomach is comparatively large in relation to the bird’s size and the solution can pass quickly into the hummingbird’s intestine facilitating the generation of energy in a very short space of time. Hummingbirds however cannot survive entirely on the sugary juices provided by flowers and bird feeders, they require proteins gained from searching out invertebrates such as insects and spiders; this is necessary for growth and essential metabolic functions, and especially important during the rearing of offspring.

A Bit Flash

The skin, hair and feathers of most animals are usually made up of pigmented surfaces that absorb some light wavelengths and reflect others which we see as colour. Hummingbirds also have the advantage of irridescent plumage which is made all the more noticeable with sudden flashes of bright colour.

Irridescent feathers have a different structure from non-iridescent feathers which allows light to be refracted rather than reflected back; the process occurs at different levels in the feather and the light combination results in irridescence – some wavelengths combine and cancel one another out, while others combine and intensify the colours we see. The angle that light hits the feathers and our view point results in us seeing bright flashes of intense colour as the bird moves.

The great thing about hummingbirds is that you don’t have to go far to see them.

In the summer of 2014 I spent a week photographing rufous hummingbirds coming to feed on bee balm flowers in our local public gardens not far from the house. It was clear that when we had a garden of our own we might easily plant appropriate flowers to attract the birds in, and anybody living in the Americas can do the same. I noticed the birds had feeding patterns – early in the morning was best if the light was good, because they were eager to get started and the flowers were brimming with nectar. Young birds had recently come off the nest and I had to be quick to get shots of them because the siblings were very competitive over this small patch of food scrapping and chasing one another relentlessly.

Hummingbirds do well feeding in small gardens, but sadly they have to run the gauntlet of urban cats. This isn’t a favourite subject for some cat owners who are in denial about what their cats really get up to once out of doors. Domestic cats kill more hummingbirds in North America than any other predator, and by a large margin so it makes sense for those who wish to attract wild birds into their gardens not to keep one.

Going South

When we lived in New Zealand I created a native wildlife garden from scratch and it didn’t take long to realise that the key to success in attracting native birds was improved pest control, available nesting sites, and the provision of appropriate food plants. Coming from Europe, nectar feeding birds were a novelty and so we were especially keen to attract in the honeyeaters – these members of the Meliphagidae family which includes tuis and bellbirds, species that were almost non-existent in our garden when we arrived in 2002, but prolific by the time we left in 2010.

Today, our New Zealand neighbours are woken by a dawn chorus of native birds, something that would have been unthinkable on our bird silent property when we arrived. The native garden not only provides an important energy source in the form of nectar for birds, it also feeds many insects which provide the honeyeaters with their essential proteins – and the same is true for hummingbirds in the Americas.

Planting a rich nectar source in a garden is a no brainer, but it must be done withouth the use of toxic insecticides, which in any case shouldn’t be necessary if a garden is busy with insectivorous birds.

See ‘So Long New Zealand and Thanks for All the Sheep.’

Mexico

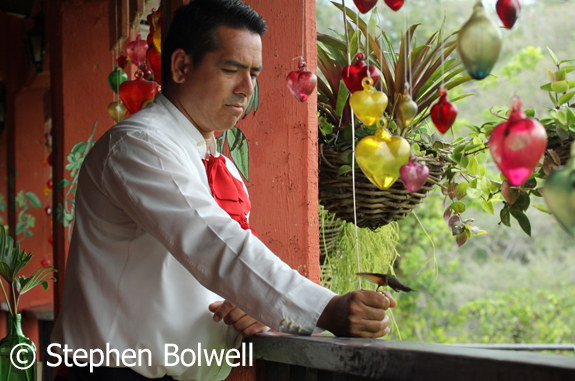

A recent trip to Mexico provided us with a chance to see a variety of hummingbirds that we never get in Canada, and at the start of the rainy season there was no shortage of opportunities to observe them. With that intention we spent several days in Vallarta Botanical Gardens, a place so packed with flowers, it fulfils an important secondary purpose supplying energy to nectar feeders.

Outside of the gardens in the surrounding environment it was possible to see the occasional hummingbird, but in the gardens where there was a super-source of food, there were dozens to be observed through the course of a day with very little effort.

If the loss of natural habitats continues at the present rate, gardens and reserves may provide the best chance of survival for many species of plants and small animals. Certainly hummingbird nesting habitat is rapidly disappearing and although a great garden surrounded by protected woodland and scrub isn’t a longterm solution, until we wake up to the problems of habitat loss and instigate a more harmonious relationship with nature, it is the sort of place that will help and, in the end, may prove essential.

Seldom have I felt more comfortable than in Vallarta Botanical Gardens at the beginning of the rainy season when it is busy hummingbirds.

A restaurant on the top floor of the visitors centre provides great margaritas and fine Mexican food; it also offers stunning views, not just over the river and surrounding forest, but closer to the balcony rail there are hummingbird feeders that are constantly busy.

One thing I saw in the garden I’d never seen before was hummingbirds feeding on bromeliads. the botanic garden has an extensive collection and it is difficult to know which plant will be getting the next visit. My wife Jen acted as a spotter, which is very considerate with afternoon temperatures pushing past 100ºF.

On returning to B.C. we quickly discover that there is little change in our local weather since we left, but despite less than ideal conditions, hummingbirds were still visiting our garden flowers.

We moved to our new house in the spring of 2015 and almost before I did anything else I was putting in plants with flowers attractive to the hummers and it didn’t taken long for rufous hummingbirds to find them – this year the flower count is higher and the rufous are now here feeding on a daily basis. Maybe we will get to stage where we don’t stop whatever we are doing to marvel at their extrordinary beauty and stunning aerial ability… but so far, there seems to be no chance of that happening.

I will continue to take pictures of hummingbirds wherever I see them. If you have local birds that are easily captured on camera then please do the same – keeping a pictorial record of species whenever possible is essential because we can never be certain how much longer they will be with us; even if it were true that every time a hummingbird arrives – time stands still.

With thanks to Vallarta Botanical Gardens. www.vbgardens.org

Thanks for sharing this informative and interesting article, made even better with a great selection of images.

When I visited the PV Botanical Gardens in March there were very few hummers, just a few rufous. I only saw one other on my ten day trip. Everyone I spoke to wondered where they had all gone.

Thanks for that information John. I won’t pretend to be an expert on hummingbird movements, but my understanding is that the rainy season is the best time to see these birds in the PV region and we were right at the beginning of that. Out of the tourist season also provided us with a better deal which made our trip affordable. Now and again you just get lucky – I think a little rain often pays off when searching out wildlife.

The other day I used the garden hose to fire a fine burst of water at a female rufous hummingbird to see what she would do – it was hot and dry. To my surprise she kept coming back for more, hovering at a point where the spray best suited her – I don’t know the exact reason, but she certainly wasn’t drinking. I can only assume that she was either cooling down or taking a shower.