As a teenager I played cricket –

that was in the 1960s. For generations during an English summer it was impossible to avoid the game, especially at school where it was considered character building to have a hard ball hit or thrown at you with sometimes lethal force.

Way back then, on a sunny sports enforced schoolday afternoon, I was fielding in one of those ‘dangerous’ too close to the batsman positions that intelligent people avoid, and perhaps realising this, my sports master shouted, ‘Wake up Bolwell… pay attention!’ which was a surprise… because I thought that I was.

Then something interesting happened – which sounds odd, because I’m talking about cricket… Anyway, the very next delivery, the ball came hurtling down the pitch at a ferocious speed, took an outside edge off the bat and came flying in my direction at considerable speed. My natural reaction was to get out of the way, but the ‘pay attention’ comment had irritated me, and I suddenly found myself diving low to my left and somehow, managed to make the catch. I got up from the ground with minimal fuss, and casually returned the ball to the bowler – surprisingly, I had no pain or broken fingers.

As the batsman made his way back to the pavilion, this extraordinary dismissal received a spontaneous round of applause from all who witnessed it, and a mildly obscene expletive from my sports master who could hardly believe his eyes. The odd thing was, none of this had anything to do with me – my finest sporting moment was a reflex action – simply a case of being in the right place at the right time… which usually, I am not. Disturbingly though, when it comes to rare mass extinction events, I, along with the rest of my generation, are in exactly in the right place because we appear to be right the middle of one, although recently it was decided that this new period kicked off around 1950, close to the time when I was born; I’d like to think it had nothing to do with me and would prefer to push it back a little further – to the industrial revolution perhaps, or maybe even earlier, to the time when humans first began eliminating big mammals, decimating forests and pushing carbon into the atmosphere, because that’s when it really started, but go that far back, and the period already has a name. So, it has been decided we are kicking off the Anthropocene around about now – the point at which we are destroying the Planet’s natural systems quicker than they can bounce back from our careless behaviour, and this is a far bigger game than most of us are ready to play… we can dive in any direction we like, but so far, we’ve made very little ‘difference’ to all the ‘differences’ we are making.

My initial contribution was to promote awareness by filming wildlife documentaries, but did that make any difference?… None whatsoever – other than to fool people into thinking that there are plenty of animals left and nothing to worry about. Heck, there’s still plenty of optimism out there – the sort that rats have when they are swimming for their lives in a water filled barrel, rather than face a certain future of drowning.

My initial contribution was to promote awareness by filming wildlife documentaries, but did that make any difference?… None whatsoever – other than to fool people into thinking that there are plenty of animals left and nothing to worry about. Heck, there’s still plenty of optimism out there – the sort that rats have when they are swimming for their lives in a water filled barrel, rather than face a certain future of drowning.

Fast forward ten years from my catch of a lifetime and I’m with a film crew driving across one of the remotest parts of the Serengeti and one of our group is about to have a light hearted go at my behaviour, providing me with an opportunity to top my greatest sporting moment by being a little too smart for my own good.

For a week or more the four of us had been driving across this huge plain looking for wildlife to film; but this was no conventional safari along well worn tracks; we were miles from anywhere crossing a huge open expanse of dry grass, mostly just hoping to ‘not break down’. The land ran flat in every direction until it reached the sky at which point the Earth’s curvature was discernible; and when the vehicle was stationary and the engine stopped ticking, I was certain I could hear my heart beating.

But we’re not standing still, instead we are moving as fast as the old Land Rover will go. I’m on the back seat, reading a book, and the cameraman who is sitting up front, looks over his shoulder and says. “If you’re going to see anything, you’ll need to pay attention”. And just as with the cricket match… I thought that I was, because in this environment it is easy to read a book and regularly scan an outside world where so little is going on. Then, after my verbal shake down, everybody went quiet, and I said very casually, ‘There’s a dead elephant on my side of the vehicle’.

But we’re not standing still, instead we are moving as fast as the old Land Rover will go. I’m on the back seat, reading a book, and the cameraman who is sitting up front, looks over his shoulder and says. “If you’re going to see anything, you’ll need to pay attention”. And just as with the cricket match… I thought that I was, because in this environment it is easy to read a book and regularly scan an outside world where so little is going on. Then, after my verbal shake down, everybody went quiet, and I said very casually, ‘There’s a dead elephant on my side of the vehicle’.

Now they’ve got their binoculars going out the window and they can’t see anything… finally they decide I must be joking and we drive on. A minute or two later without looking up I say, ‘The dead elephant’s about half a mile directly to the left now’… and still they don’t see it and I’m beginning to wonder, ‘Is there really is a dead elephant out there?’ but I continue to read my very bad book whilst giving directions. Then somebody says, ‘It’s just a mound of earth’.

“It’s a dead elephant”. I persist. “if it was just dirt, it’s too spread out for a termite mound… and I don’t see any dumper trucks.” I’m really pushing my luck now, because everybody is irritated by my attitude… and the detour – so I really need a dead elephant out there somewhere because nobody likes a smart Alec.

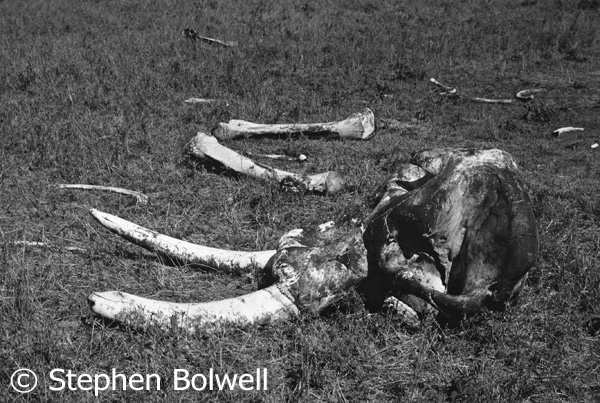

Eventually we arrive at this spread of huge bones – they’ve been stripped clean by scavengers, but otherwise are only a little more spread out from the time when the elephant died. Robin Pellew our science advisor is an expert on giraffes, but has spent enough time on the Serengeti to know that here lie the remains of a male elephant of about 40 years of age, with no clear indication as to cause of death.

This elephant skeleton discovery occurred on the afternoon of 12th November 1979 and was not due to any personal skill on my part – I was born with good eyesight and that’s not something you can practice. Today though, imagine how remote you would have to be to stumble across a dead elephant that had been laying around undisturbed long enough for it’s bones to be stripped clean… Well, maybe not so long when you consider the size and number of scavengers on the Serengeti, but it was extraordinary to find an elephant’s skull still intact with both tusks in place, propping up the front end like some well balanced sculpture.

I’d like to say we took some pictures and drove respectfully away, but we didn’t do that. We took some pictures and then set about smashing the front of the skull with a tyre lever to remove the tusks, which we then tied to the roof of our vehicle so that they might be delivered to Serengeti Park Headquarters, rather than left for others to find and sell into the ivory trade. The tusks were over five and a half feet long, and it’s not until you’ve tried to separate tusks from an elephant’s head that you realise just how much lies embedded in the skull – about a third – and by the time I’d finished my share of skull bashing to get them free, I didn’t feel quite as smart as I had done before we started out on the task.

By the end of 1979, at the time when we brought back the ivory, the African elephant’s heyday was already over; we’d been looking to film elephants during a period of heavy poaching and it is important to realise that all of us are somewhere on a timeline, and more often than not, few of us get to see the beginning or the end of a great many processes. Elephants were heavily poached from the beginning of the 1970s, and by the end of the 1980s things were much worse. Often there simply wasn’t the man power to deal with the increasing problem, and invariably the conservers were outgunned. Well organized Somalian poachers with automatic weapons began dropping down into Tanzanian parks and when they met opposition, it was poorly paid wardens attempting to protect both the elephants and themselves with old Lee Enfield rifles left over from the First and Second World Wars.

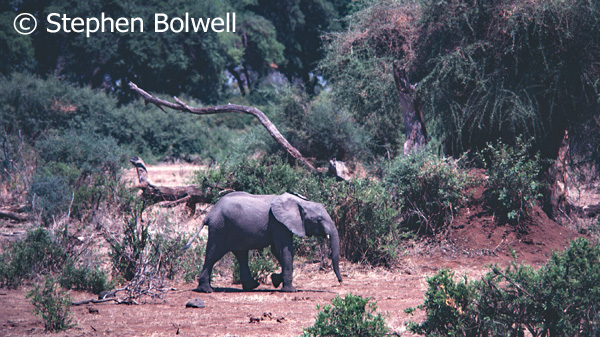

African elephants are the largest land mammals still living today, but the savannahs they inhabit are extensive, and so protecting every herd let alone every individual has proven impossible, especially taking into account the corruption that has plagued so many parts of Africa over the years, enabling the illegal killing of animals to continue despite the best efforts of conservationists.

The message did seem to be getting through for a while and the situation for African elephants improved during the 1990s when their numbers began to rise, but this is now recognised as a blip on what has otherwise been a rapidly descending curve.

The most comprehensive aerial survey of elephants ever undertaken has recently been completed; this essential project was largely bankrolled by the philanthropist and co-founder of Microsoft, Paul G Allen, and the results have provided some sobering figures that show a serious decline in the number of elephants on African savannahs. The losses are mostly down to poaching, which has become increasingly problematic in East, West and Central Africa.

A summary of elephant status over the years: http://www.greatelephantcensus.com/background-on-conservation/

Elephant populations across Africa have dropped by one third in the last decade and if poaching continues at the present rate half of the remaining animals will be gone within the next ten years.

Presently, there are estimated to be a little over 350,000 elephants wandering across the savannahs. But before Europeans arrived on the continent there were probably more than 25 million, and you can’t help but think how destructive our species is, when elephant populations have been so thoroughly decimated in just a few hundred years.

The Survey: https://peerj.com/articles/2354/

When I was a small child in the 1950s it is thought that around 250 elephants were killed in Africa every day, notably at a time when African nations were gaining independence. But that’s not to imply that Africans are responsible all of the killing; for a century or more hunters have arrived from outside of the continent and paid huge sums of money for the pleasure of shooting one of nature’s greatest wonders.

As the human population of Africa increases, more land will be taken from the natural world – in particular for agricultural use. Increasingly this is a matter of life and death for elephants, because their presence is not easily tolerated close to people. By any terms elephants are destructive, and unless they have space to do their own thing, they will increasingly make regular contact with humans and come off second best. This is not a new story, elephants have always been a nuisance to people, especially when they destroy crops, and the frustration of farmers is understandable.

As the human population of Africa increases, more land will be taken from the natural world – in particular for agricultural use. Increasingly this is a matter of life and death for elephants, because their presence is not easily tolerated close to people. By any terms elephants are destructive, and unless they have space to do their own thing, they will increasingly make regular contact with humans and come off second best. This is not a new story, elephants have always been a nuisance to people, especially when they destroy crops, and the frustration of farmers is understandable.

Unfortunately, domestic stock animals are an additional problem for conservationists, they are driven into many natural areas to graze and this presents a threat to wildlife either through direct competition, or by spreading diseases across huge areas of what was once recognised as elephant country; and even national parks seem incapable of keeping essential conservation areas free from the intrusion.

In the developed world we destroyed most of the large mammals that competed with us centuries ago and it is a pattern that continues to repeat itself elsewhere. The process started when man became a successful co-operative hunter, took readily to barbequeing and then agriculture. From a slow unsteady start the human population began to grow exponentially and this continues to the present day. Our population expansion is beyond natural control which has proven devastating to many other species.

Never before has human population growth been so consequential, with many countries on the continent having a doubling time of between 35 to 50 years. Which means that if poaching stopped tomorrow, we might be asking where in any case would there be enough space, even in a place the size of Africa, to fit in the next generation of hungry elephants alongside a competing, and more likely to succeed, rapidly increasing population of Homo sapiens.

But even ignoring all of that, the biggest problem that African elephants currently face is their habit of wandering around with thousands of dollars of comparatively easy money growing out of the sides of their mouths. For millions of years, having a couple of really useful big teeth was advantageous and made elephants the biological equivalent of bulldozers with a forklift truck attachment at their front ends, but of course these front ends were never meant to be detached. Over a few tens of years really useful tusks have suddenly become a serious liability, and with a long lived slow reproducing species evolution doesn’t have any short term answers. There are no other serious predators to adult elephants, their continued survival is quite simply down to us.

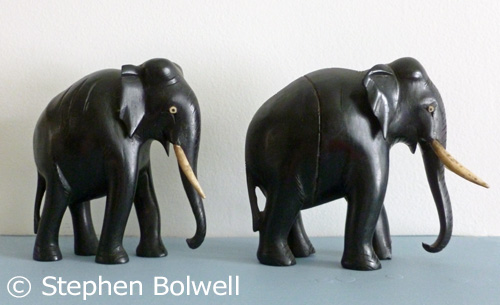

It would not of course be such a problem if ivory was less desirable and so much in demand in certain key places in the world – mostly Asia. Not so long ago the Japanese found ivory invaluable for making seals as personal signatures. In Europe ivory carvings were imported from the Far East, which is the home of traditional ivory carving. This material has also been a popular inlay and widely used to embellish instruments, most famously piano keys – in Britain piano players were once said to be ‘tickling the ivories’. Today however the market is centred in China, and Vietnam where skilled craftsmen still carve ivory to supply both the home and world markets, and it remains available on the black market even in countries where the sale of ivory is now illegal.

Culturally it has been easier to persuade the Western world that they don’t need ivory than is the case in the East where the problems elephants face has been slow to be recognized. There are few places in Europe where people remain unaware that poaching ivory is bad news for elephants – and really… how long does it take to come to that conclusion? A partial ban on ivory has existed in the U.S.A. since June 1989, but it was not until June 2016 that an almost total ban came into law – better late than never I suppose.

Once upon a time ivory was a status symbol in Europe and North America, but attitudes are changing, and increasingly the general ownership of ivory is considered to be in bad taste. It has over the years simply been a matter of education to persuade people that the best place for ivory is at the front end of an elephant on either side of its trunk.

In China the carving of African elephant ivory and rhino horn along with its use in Chinese medicine are still ‘culturally significant’; and it takes time to eliminate anything that comes under that heading. The horrors that have been committed in the name of God and the ‘culturally significant’, are, sadly, too numerous to mention.

Chinese authorities have recently been campaigning against the use of ivory. Even Jackie Chan has spoken out on the subject of ivory poaching and he’s probably made a difference. I was never sure why I liked Jackie Chan, but now there is a very good reason.

Back in 2014 WildAid surveyed China’s three largest cities to gauge changes in attitude towards poaching and the ivory trade, making comparisons with a previous 2012 survey. In 2014 just over 70% of participants thought that elephant poaching was a problem; well up on the ‘a little over’ 45% figure from 2012. An increase of over 50% for the enlightened view, which at least offers encouragement that attitudes can change.

For more details of the survey: http://wildaid.org/sites/default/files/resources/Print_Ivory%20Report_Final_v3.pdf

An online survey also found that 95% of respondents supported an ivory ban, but the key word here is ‘respondents’ – I wonder if those who responded were more likely to do so because of their positive view. I also wonder about the sample size, 1500 people – 500 hundred from each city, doesn’t seem a very big sample considering the millions of people living in these centres of high population. Whatever the surveys are telling us to sweeten the pill, there is still a significant amount of ivory being traded, and elephant numbers continue to plummet. Time is running out. Personally I don’t get too excited about surveys, preferring instead to put emphasis on results. The answer might be to just stop trading with any country where people continue to deal in endangered animal parts as a matter of course, even if in the mistaken belief that such items have medicinal value, when scientific evidence demonstrates that they do not.

Presently, there are many people trading in endangered animals and body parts with impunity, and the rarer an animal becomes the higher the price gets, which only adds to its appeal. Education is one thing, but taking on ‘the money’ is never considered a realistic option and all too often ends up in the ‘too hard basket’; but now it really is far too late in the day to dither, because if nothing changes in the near future, we will all soon be saying ‘goodnight Jumbo’.

The obvious answer is a two pronged attack, education across all social groups whilst also taking out those who trade at the top end of the market where the profit margins are the highest – but of course those involved in taking the largest profits don’t like that idea at all, and won’t be going without considerable resistance.

At the end of the day the obvious problem remains – until African elephants are worth more to people living in Africa alive than they are dead, the decline will continue, because the corruption that maintains the present situation is going to be a juggernaut to stop.

Without doubt – the answer lies in persuading people that paying good money for ivory is stupid, and if that idea could be wedged into peoples brains then the ivory trade would be finished. The solution, if there is one, isn’t going to be a walk in the park. Or should that be ‘a stroll across the Serengeti’… I’ve tried that, and it’s not so easy. I’ve also done my fair share of filming and photography – it has made very little difference.

Without doubt – the answer lies in persuading people that paying good money for ivory is stupid, and if that idea could be wedged into peoples brains then the ivory trade would be finished. The solution, if there is one, isn’t going to be a walk in the park. Or should that be ‘a stroll across the Serengeti’… I’ve tried that, and it’s not so easy. I’ve also done my fair share of filming and photography – it has made very little difference.

We know how wonderful elephants are – but nothing that we are presently doing is saving them. Perhaps if I was still living in England I’d say that the continued persecution of elephants ‘just isn’t cricket’ – but a sense of fair play isn’t going to get us anywhere in the face of almost insurmountable greed and mind blowing ignorance, and as always… more than a fair share of plain stupidity.