The banks of New Forest streams have changed significantly over the years.

Long before I started photographing the New Forest in the 1970s streamsides were steadily being opened up by livestock as they grazed and trampled these fragile areas into blandness, and it is a problem that continues to the present day.

If managing the open Forest continues to prioritise traditional practices, then maybe it’s not such a bad idea to refer to photographs taken earlier in the 20th Century to gain a better understanding of the changes that have occurred.

Many stream banks were grazed out long before I began taking pictures in the early 1970s, but nevertheless, I have still managed to record many changes over the years, often without the realisation that I was doing so. When I started out, the New Forest was already heavily grazed and I had not expected things to get worse, but generally they have, with very little in the way of critical comment.

The picture below was taken in the Spring of 2016 at the the edge of a heathland that I know very well, this about 100 metres from the pond that I discussed in my previous article, although it is not necessary to have read it to comprehend the changes discussed here. Over grazing has certainly degraded the surrounding heathland, but things get far worse on approaching the tree line.

- In the 1970s this was a much different habitat than today, with heathland to the left and extensive patches of undergrowth running along the tree line and the stream side just beyond the trees to the right.

The broad band of vegetation that ran along this side of the trees was made up largely of grassy clumps of bog myrtle and patches of bramble, which made this an especially good place to photograph adders during spring. The present habitat is extremely degraded and most of the heather has now disappeared. All of the low cover that bordered the stream side has been eaten out and is rapidly becoming a lawn that is not well suited to any species of snake.

This location has extensively changed even since the beginning of the new Millennium.

At one time the surrounding heathland provided a variety of habitat types suitable for all three British species of snake. Within an area of about 500 hundred square metres there was mature heathland that ran into heather of various ages, before arriving at a pond and a stream side both of which had banks covered in undergrowth. This is important because there are but a handful of places in Britain now where you can find all three British snake species in close proximity and most of these locations are in the New Forest.

On severaI occasions I was fortunate to film the adder dance in undergrowth along the stream at a time when it was less heavily grazed and I was present when an adult male climbed up through a gorse bush to investigate a dartford warbler’s nest. During spring it was commonplace to see a dozen adders over a one hundred metre stretch here. On returning to the streamside during the spring of 2016 I searched for three mornings in ideal weather conditions but didn’t find a single snake.

Trust me, I’ve put in the hours.

You know how it is if you want to place a bet – say, on who will win the next general election… Past experience tells us that is unwise to rely on pundits or exit polls to make a winning decision. The best option is usually to look at the odds a bookie will give you – because if they keep getting it wrong they’re out of business and clearly there is no shortage of bookies. I won’t claim to be an expert on every plant and animal on the Forest, but when it comes to snakes I am a bit of an adder bookie; if you want to know where they are, then I’m the person to ask – I once spent months of the year finding and filming these beautiful reptiles and how many people can honestly say they’ve paid their mortgage by watching snakes. I won’t go as far as to claim there are no snakes left at my favourite filming location, but even a glance reveals no suitable ground cover for snakes in a place where they were once common, which makes the odds on finding one pretty slim.

I am using the adder as an indicator that represents a general decline in the numbers and diversity of many other species; everything from rodents through to invertebrates have become more scarce here during my years of observation and once again I am speaking about animals that were once common. The tendency is to dwell on the disappearance of the more showy – butterflies and moths for example, for which the species in decline list is long; but I will chose one species only, and it is a plant rather than an animal. I have noticed that there are now far fewer sundews than there once were at this location. I filmed them many times during the 1980s and 90s, when they were common in boggy areas. This is a species that does well on wet heathlands when grazing is optimal and the decline suggests that grazing levels have become too extreme.

Only a short walk away there is another site that also provided an ideal adder habitat.

During the 1970s and 80s I regularly filmed adders on this bank, but none can be found here now. The bank, once protected by inclosure, has more recently returned to open Forest and in consequence is heavily grazed. I accept that Forest plantations are not inclosed indefinitely, but those that are fenced will grow deep heather along their borders because of the reduction of grazing pressure. This location is about half a mile from the degraded streamside I have already mentioned, and it is difficult to understand how so much habitat appropriate for snakes, along with many other plants and animals, has been allowed to degrade over such an expansive area. The situation is depressing and it would perhaps be kindest to suggest that this is no more than a case of careless management, because it is difficult to believe that the real priority has been to open up yet more Forest for grazing to the detriment of almost everything else.

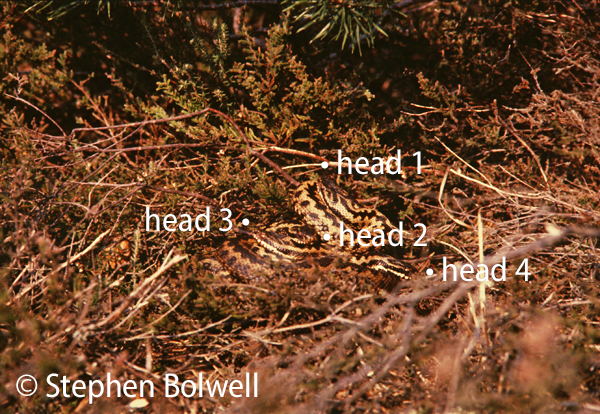

Here is the bank as it was during the 1970s

Without the labels in the above picture, you might not notice the snakes at all – their markings disguise them almost perfectly amongst the heather which was once the most dominant plant. Part of the problem is that older heather is especially brittle and when the inclosure fences came down the whole area was trampled by livestock. Herds of cattle will lie down in different places each night and this destroys the heather base and damages the habitat.

And it’s not just the snakes that have disappeared:

the band of heather that once ran along the tree line was, during the 1970s, teeming with invertebrates. I know this because I sweep netted the area regularly to identify the spiders and insects that were present. Heather cover is akin to a miniature forest; different animals live at different levels and many will rise to the top on warm sunny days where their presence will provide food for a variety of other creatures.

With the destruction of its heather the site has now become barren. Gorse will eventually regenerate, but if the pressure of livestock is not reduced the heather will not be able to. This is a common pattern repeating itself across the open Forest…. There’s something not quite right here – the environment is rapidly becoming sterile and there should be cause for concern.

It isn’t just the act of munching that is a problem, it is also the peripheral activities undertaken to support it. Back in the 1960s as a teenager I witnessed wetlands being drained to increase the availability of grazing and that proved to be a disaster for many wetland species. Some bog areas have more recently been re-instated, so it isn’t all bad news, but burning and scrub clearance to promote a browser friendly habitat continues, which inevitably has an impact. When things all begins to look the same, wildlife diversity always suffers.

Most New Forest woodlands that are not within a fence line are also overgrazed.

The open woodlands, just like the open heathlands are also disappointing – many now display very little ground cover due to heavy grazing and this has had a knock on effect, reducing plant and animal numbers along with species diversity; in particular it has affected the many small animals that rely upon low spreading plants for food and shelter.

The New Forest suffers greatly in terms of the fine details. Almost nothing vegetative survives here unless it remains out of the reach of grazers: much that can be eaten will be eaten – by ponies, cattle, donkeys, pigs and deer – the munching is relentless.

When you have seen old beech trees growing from childhood and they are suddenly damaged in this manner it is difficult not to become despondent. Some of the older pollarded trees on the Forest have been standing for more than three hundred years; it is likely that some trees were planted, but many others will have self-seeded.

Due to a hard grazing regime, the survival of trees that seed and grow naturally is now almost zero. Dense undergrowth such as bramble which was commonplace in the past allowed native tree seedlings some protection from hungry mouths, but today there is very little undergrowth available to act as nurseries and very few young trees survive the onslaught.

I also found time during my Spring visit of 2016 to go to a friend’s privately owned property situated next to the open Forest; it comprises fields, pasture and what interests me most, a fenced off woodland.

I well remember going out on the open Forest during the 1990s to film the fallow deer rutt and on early mornings it was common to find inclosure gates wedged open by pieces of wood to allow livestock in… Not content with destroying the fabric of the Forest, some locals felt that natural undergrowth protected by inclosure was simply a waste of grazing potential.

In the private woodland things couldn’t be more different. The soil type is the same as on the adjacent New Forest, but free from ponies and cattle the understory looks healthier; and any stock animals that do find their way in are soon put back out.

There were also quite a lot of other plants in bloom, this to the advantage of a variety of attendant invertebrates, in particular insects feeding on the variety of wild flowers.

It’s spring, so there are also primroses amongst the wood anemones.

And just in case you aren’t convinced, the next day I was back in the New Forest and the contrast was quite shocking.

Many other treasures will become evident in the private forest as summer approaches, whilst back on the open Forest there will be little in the way of food plant such as bramble flowers that adult butterflies and other insects need to feed on, and very few plants for butterflies to lay their eggs on which their emergent caterpillars require as a food source. All of the action will be happening in the private wood; and any butterflies seen flying across the New Forest will, most likely, be passing through in search of somewhere more useful, and a good deal more interesting than the convenient dog empying fascility that the Forest has become.

In Victorian times there were descriptions of butterflies rising on New Forest rides in such numbers that it was difficult to see down them. Such radical change over the last 150 years is not unprescendeted elsewhere, and such changes are not entirely due to grazing regimes, but the extremes of change over periods a little too long to notice in a human lifetime is nevertheless disturbing.

So what’s gone wrong?……..

The answer is complicated – the New Forest came under the auspices of the Forestry Commission in 1924, and commercial forestry did not always sit well with the needs of conservation; sadly, too many native deciduous trees were felled to make way for alien conifer plantations.

In consequence there was a decline in species across the Forest under the new tenure, but there were other factors to consider: rapid urban development was beginning along the New Forest borders; pesticides and herbicides were coming into general use and people began visiting the area in greater numbers. This was a period of considerable change and it would unfair to lay the blame entirely at the feet of one organisation.

In 1969 the Forest became a National Nature Reserve and the Forestry Commission began working in unison with the Nature Conservancy (now Natural England), a relationship that was strained at times but in retrospect, relatively successful.

In 1971 conservation measures were undertaked in a more organised manner as the Forest was declared ‘A Site of Special Scientific Interest’. Nevertheless, how intensely the New Forest should be grazed has for many years been a thorny issue . The subject will always be controversial, because those with grazing rights believe the well being of the Forest relies almost entirely upon them – they are it seems doing us all a favour and views to the contrary are not often well received.

The British have a long history, and so it is understandable that sometimes they look backwards to earlier times to find solutions for current problems, when perhaps it might be wiser to be looking to the future; and the New Forest is no stranger to this approach.

For as long as I can remember management policy has never been entirely driven by science based evidence directly linked to the New Forest’s flora and fauna, because it has always been difficult to separate the uniqueness of this place from historical tradition – but the world is changing. Ancient Forests have all but disappeared now and it is essential to consider every aspect of their conservation before deciding how best to manage them.

The effects of grazing must be more carefully considered and take precedence over Commoner’s rights, because the Forest isn’t best served by maintaining age old traditions to the exclusion of everything else, and recent additional grazing subsidies will certainly have clouded the issue. Sadly, what is best for the environment is not necessarily decided by logical argument. Politically, it is easier to favour a traditional way of life over nature itself. When you live in a democracy nature doesn’t get to vote.

The intention has always been that tradition and nature should work together, but any argument that puts outmoded ‘rights’ before the realities of the current situation makes no sense and the present lack of an appropriate response is tiresome.

Looking at the British countryside from the air, demonstrates that much of what remains outside of standard agricultural use is grazed by livestock – in particular sheep – thus prohibiting any possibility of a return to wilderness. Indeed, the British National Park mentality sees cropping by domestic herboivores as essential to maintaining ‘a traditional look’. It is as if we are too frightened to allow wilderness to return to Britain. Policy makers seem set against allowing the natural world to make a comeback, which is unfortunate because a little bit of ‘wild’ is good for us and even better for the environment.

In the New Forest it certainly isn’t too late to make a change for the better by reducing livestock. In the short term, private landowners will carry the burden of maintaining wildlife diversity on adjoining properties until ‘common sense’ prevails over ‘common rights’, although making changes remains an uphill battle.

Most environmentalists recognise the benefits of grazing as a conservation tool, but it has to operate at an appropriate level. Clearly this isn’t happening in the New Forest. Britain’s most recently designated National Park is increasingly, looking like a badly worn snooker table and it makes sense to be honest about the direness of the situation. At the very least the problem needs to be recognised and those in control politely asked to start making intelligent choices that are long overdue.