It’s nothing personal – lurking in every human brain is the potential for stupidity.

Most of us think, or at least hope, that there are people out there who are far stupider than we are; and the confidence this provides, helps us feel better about ourselves; which suggests perhaps that we don’t live so much in the outside World as much as inside our heads, experiencing a virtual world brought about by our brains interpretation of external stimuli. Whatever the case, few of us are critically analytical about the way we think, or question why our brains work the way they do.

The prime function of any brain is to guide its owner through the complicated game of life, and it seems that our brains are quite good at dealing with short term minor events, but long term consequential issues often send us scurrying away to develop a wait and see policy, that more often than not, is ridiculously hopeful.

Although we have the potential to do so, we find ourselves disinclined to look ahead and think proactively about really big issues. In particular any thoughts that concern the viability of our planet and the life that lives upon it will not usually provoke actions beyond the most trivial. Some might suggest this to be a sign of stupidity as we have proven woefully incompetent at analysing problems that may have serious longterm consequences.

We all have a certain potential for stupidity, and this might be something we just have to live with. The real problem is that ignorance can usually be remedied – but stupidity, like a dog at Christmas, is for life.

On a day to day basis there is of course a limit to how stupid our behaviours can become before we are forced to pay the ultimate price of prematurely checking out; but, when we restrict our particular versions of stupidity to ideas rather than actions it is surprising how much leeway we give both ourselves and others, allowing us to spread unsubstantiated views to just about anybody who will listen.

Clearly our brains are not perfect, and naturally disinclined to promote entirely rational behaviour; but nevertheless there is still a lot going on inside our heads. Most of our decisions are made by undertaking a complex series of rapid mental processes; which means that we often get things wrong, but at least we can do so very quickly.

Sense and Sense Ability.

The world about us is busy with information, but our perception of it is limited because our sensory ability is surprisingly narrow. Evolution it seems has adapted us to perceive enough of what happens around us to get by, but not so much as to overload our brains with superfluous data that won’t significantly improve our chances of survival.

We have been shaped by our senses,

and our behaviours limited by our sensory range which affects our brain’s perception – because there is a lot of information out there that we are incapable of gathering.  We can’t for example utilise the infrared part of the spectrum, as snakes do when sensing the thermal radiation emitted by their prey; or utilise U.V. light as bees do when they pick out guide markings on flowers when gathering food.

We can’t for example utilise the infrared part of the spectrum, as snakes do when sensing the thermal radiation emitted by their prey; or utilise U.V. light as bees do when they pick out guide markings on flowers when gathering food.

On some occasions it would be useful if we could echolocate like a bat, or have sense organs along our bodies as fish do, to taste our surroundings when swimming through water, but we can’t do either. Certainly our eyes do not see with the magnified detail of a hawk, and there’s no chance of smelling or hearing with the acuity of our dogs, but despite all of these sensory limitations our species has remained quite viable in the short term. But if we expect to continue, we will need to develop broader behavioural strategies to ensure our future, because the impact we are presently having on the Planet is down to our inability to change detrimental behaviours and this is beginning to let us down. In nature every species is destined to become extinct, but by the essential act of thinking, we should at least be trying to buck the trend.

no chance of smelling or hearing with the acuity of our dogs, but despite all of these sensory limitations our species has remained quite viable in the short term. But if we expect to continue, we will need to develop broader behavioural strategies to ensure our future, because the impact we are presently having on the Planet is down to our inability to change detrimental behaviours and this is beginning to let us down. In nature every species is destined to become extinct, but by the essential act of thinking, we should at least be trying to buck the trend.

Despite all of the information out there that we miss, our brains contribute impressively to external events by filling in the many gaps that our sensory abilities fail to perceive. Our eyes for example do not get to see everything that happens, but our brains usually make appropriate associations by logging into past experience before joining up the dots: this is particularly true when it comes to facial recognition, which has become a major feature of our social success – what we don’t quite see, our brain smoothes over and this extraordinary ability will sometimes make us unreliable witnesses to what goes on around us.

What we think we see often falls short in the fine detail, because our brains constantly make things up to form a more complete picture and then commit this to memory; but recalling that memory will then be subjected to changes before the rejigged information is put back into storage – in essence the more times we recall an event the further it moves away from the truth. With this in mind, perhaps we should worry less about the tiny details that we miss and analyse more carefully the ones that we don’t.

Science demonstrates that our success does not rely entirely on deriving information in absolute form, and our survival has not so far depended upon knowing all of the facts; with our brains concerning themselves primarily with short term appropriate responses to each individual’s syntheses of reality.

Our senses may not be perfect,

but the one thing we do excel at is having a generally high opinion of the achievements of our species. We should think more carefully though before allowing ourselves to become too satisfied with the length and breadth of our cleverness. The human brain is the most complex analytical organ that we have so far encountered, but with its imperfect reconstructions of the outside world we can sometimes appear a little stupid.

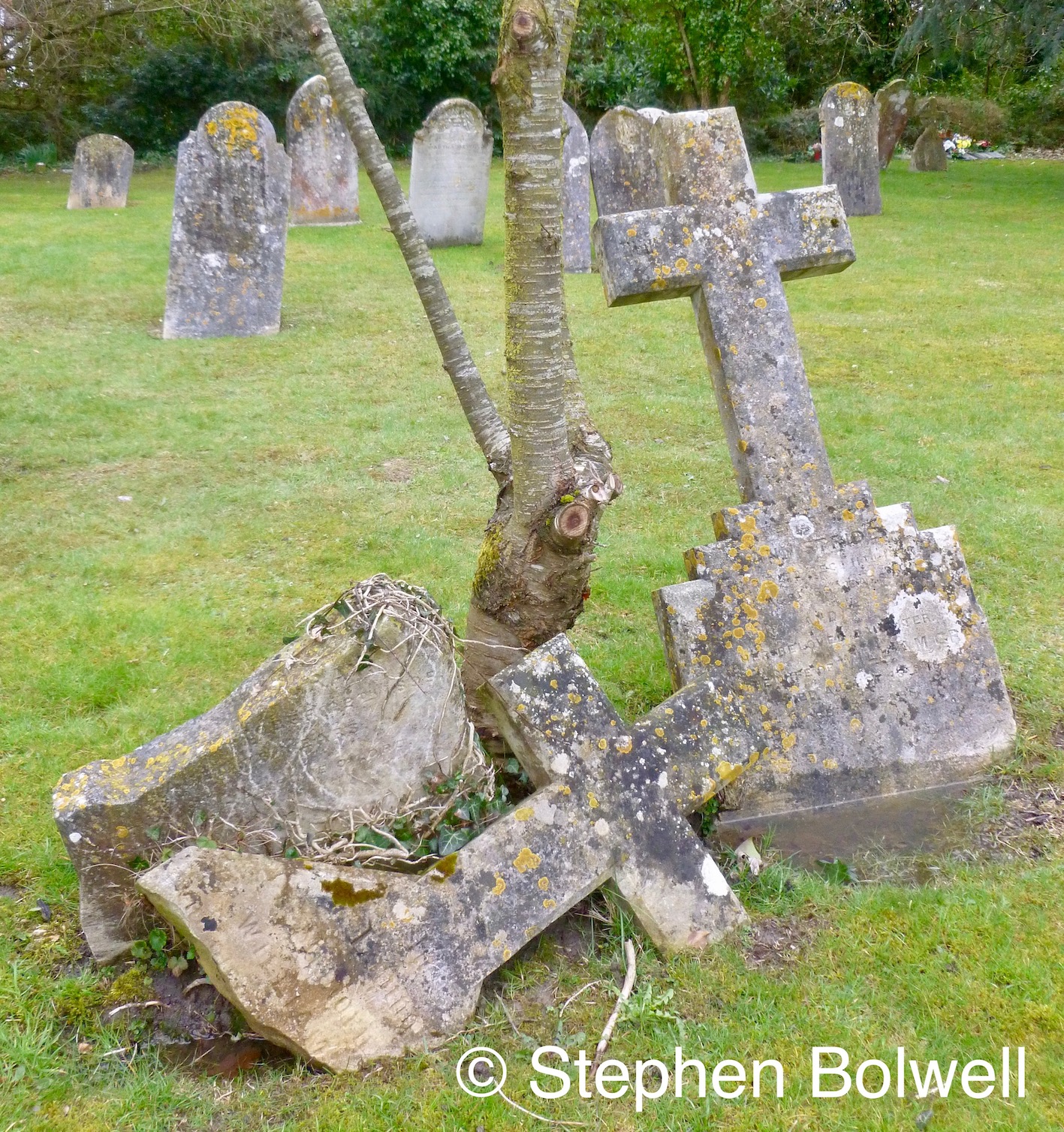

The most basic problem we face is that of perception.

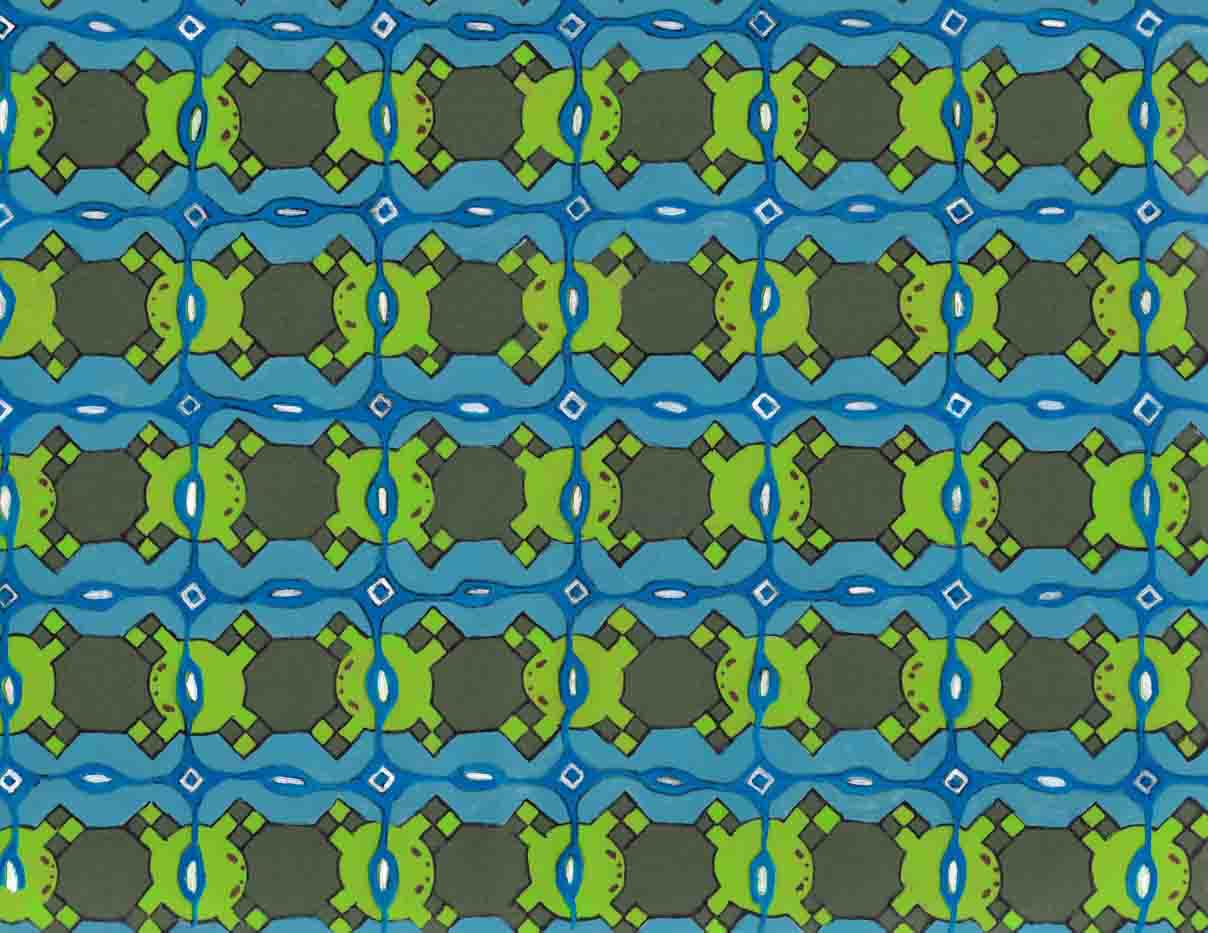

Consider that we are floating across a lake and looking down into the water and see a number of toads swimming this way and that in close formation – never mind that the image we see looks like something out of a digital dream populated by creatures straight out of a computer game from the 1980s.

Then the wind blows causing a series of waves to run across the surface of the water, which, rather like the toads appear too geometric to be entirely believable, but just go with it for the sake of argument…

Then the wind blows causing a series of waves to run across the surface of the water, which, rather like the toads appear too geometric to be entirely believable, but just go with it for the sake of argument…

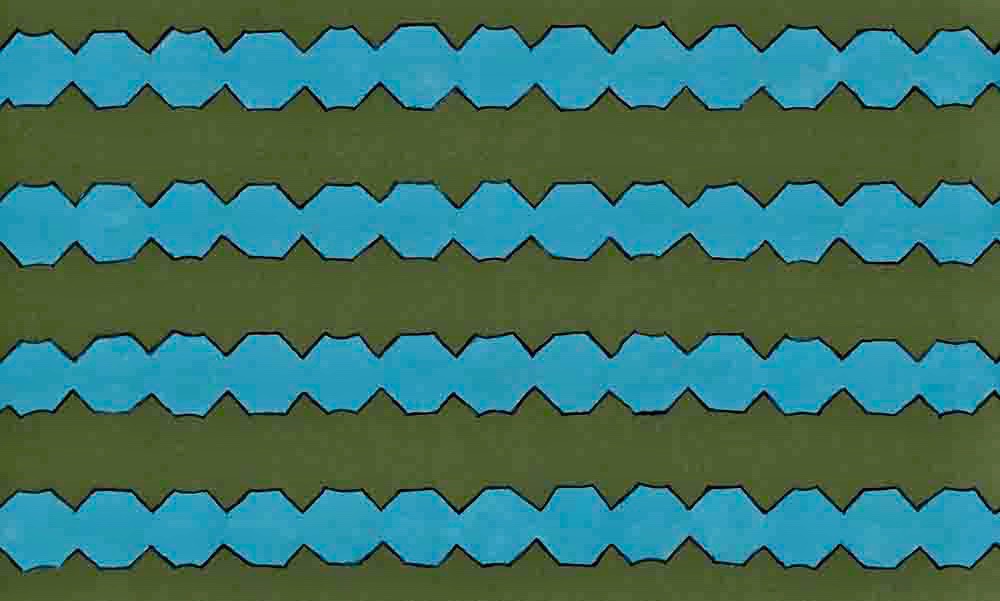

The sun comes out to add some sparkle to the little waves that run directly parallel to the lines of toads and the sparkle also forms at right angles, and now we should ask ourselves, are the waves really running parallel to the toads… I mean if you hadn’t seen the waves and the toads independently would you stake your live on the fact that they are?

Of course, what you may or may not see here really isn’t a measure of stupidity, but it is an indication that even at the simplest level our minds do not always recognise what is going on in the outside world. Our brains are fallible and on occasions our interpretation totters on the edge of getting something very simple, very wrong. Such events are called optical illusions, but more properly they are optical effects, for which the brain is often responsible when it creates cognitive illusions to explain what it thinks we have seen.

My daughter was travelling in Central America with a group of people quite unfamiliar with the area, when their driver cut power to the vehicle to demonstrate that at this particular point in the journey the vehicle was moving uphill without the power of the engine. He gave the explanation that at this place the Earth’s magnetic field ran close to the surface of the road and it was this that was drawing the vehicle up the incline. When my daughter returned in the evening to where we were staying she told me this interesting story without any sense that it was ridiculous. My reaction was unfortunate, ‘Are you stupid?’ I asked her, which didn’t go down very well as she really wanted to believe a story that had now largely been ruined by the truth, and needless to say my reaction earned me a number of bad parenting bonus points.

In retrospect I realised I had been unfair, because I had viewed the situation with the advantage of previous experience, as the very same thing had once happened to me, in another place, another time. I had the advantage of knowing that the earth’s magnetic field is a force that is spread across a huge area, but in any single place can be regarded as far weaker than even a small bar magnet, which cannot pull a large vehicle up an incline against the force of gravity. The effect is usually caused by the surrounding landscape making it appear as if something is moving uphill and is a genuine visual illusion.

At the time of my experience I was travelling as a cameraman and had the advantage of a spirit level on my tripod and another in my bag and I was able to demonstrated fairly quickly that our vehicle wasn’t being pulled uphill by the Earth’s magnetic field and was at once regarded as a killjoy, with none of the other passengers inclined towards a rational explanation, a response that I found rather odd. My daughter and I had experienced an illusion that could be easily demonstrated by performing a simple experiment with a blob of air in a small glass tube containing liquid. In fairness we are stupid only when we don’t learn from the first occasion something unlikely happens to us, as only stupid people fall for the same nonsense twice. All that I will add is that exposing an act of stupidity will not necessarily make you any friends.

At the time of my experience I was travelling as a cameraman and had the advantage of a spirit level on my tripod and another in my bag and I was able to demonstrated fairly quickly that our vehicle wasn’t being pulled uphill by the Earth’s magnetic field and was at once regarded as a killjoy, with none of the other passengers inclined towards a rational explanation, a response that I found rather odd. My daughter and I had experienced an illusion that could be easily demonstrated by performing a simple experiment with a blob of air in a small glass tube containing liquid. In fairness we are stupid only when we don’t learn from the first occasion something unlikely happens to us, as only stupid people fall for the same nonsense twice. All that I will add is that exposing an act of stupidity will not necessarily make you any friends.

Our brain usually prioritises the recognisable and will sometimes override the recognition of certain truths – our brains it seems are often busy with compromise, especially if we are dealing with one another when we often disguise – sometimes unwittingly – what we are really thinking or feeling for the sake of social cohesion. At such times, we are open to suggestions and the beliefs of others, when what we probably should be, is a bit more sceptical, at least inside our heads. Being part of a group can be good for our mental health, but it can also lead us away from the truth, and when that happens we tend to all get stupid together, although most of us don’t notice.

Clearly, the way our minds work is fundamental to our susceptibility to certain types of input. The success of advertising for example, is a clear indication that our minds are open to manipulation and young brains in particular are more plastic and vulnerable to harm from certain kinds of input, but even as we get older and more experienced the personal computing systems we carry in our heads are still open to suggestion. A lot of the time we are just kidding ourselves, because from an evolutionary perspective, that is what has worked best for our species… Well, it has so far!

More recently with the sudden explosion of digital information, things have been moving more quickly than they ever have done before, with everything from technology to the way we receive news – which is almost continuous now, along with the speed of our social interactions, which has produced a rate of input to our brains that has not worked well for everybody; and some people are discovering that they have a better quality of life when they stop checking their mobile phones and dispense with social media altogether. Nevertheless, progress is progress and receiving information quickly is the way things happen in today’s world, but that does not alter the fact that our brains may not be adequately equipped to deal with the non-stop intensity of our modern lives and some of us are simply not keeping up. The modern age has brought with it more to consider, and consequently more mistakes are made which gives the impression that there is ‘a lot more stupidity about’.

Birds in particular appear to be very adept at working things out and for them in particular, brain size isn’t everything. Birds have much smaller brains than we do, but make very good use of them because the neurons they contain are smaller and more densely packed than is the case for mammalian brains; which might explain why so many birds demonstrate cognitive abilities that often surprise us.

Animals other than ourselves demonstrate varying degrees of intelligence and their close proximity to nature means that ‘stupidity’ (if we can call it that) at the most basic level will bring them closer to death. But because humans now control so thoroughly the environments they live in, and have achieved such high levels of social co-operation, the idiots amongst us usually get considerable leeway before getting penalised. We are it seems extremely tolerant of stupidity, in part because it has many facets that are difficult to quantify and when it is difficult to quantify something it is difficult to make judgements.

Nevertheless, one might think it easy to distinguish between people who do and do not exhibit this unfortunate condition – even if today it is not politically correct to do so… although of course we all make judgements about one another in our heads. Most of us recognise a tendency in others to be a little on the dim side, but we still fail to call it when a well educated professor, brilliant in his field, finds it difficult to achieve simple practical tasks that a poorly educated streetwise kid can manage in a second… Critical thinking should not be confused with intelligence, as stupidity is clearly relative as well as complicated.

‘The Dunning-Kruger effect’

is a cognitive bias that demonstrates one of the saddest ironies of the human condition. David Dunning and Justin Kruger showed that people who have the least competence at a task often have a tendency to rate their skills more highly than do people with greater competence; in effect these are people too ignorant or stupid to grasp what it means to have the skills to ‘think about things’ in the first place; and if we are happy enough to label such people ‘stupid’, the important thing to remember is that they will not have any realisation of their situation because they lack the capacity to reason with the necessary awareness to have the faintest idea of how stupid they really are.

In the end the reliability of the way we think is a subject that many of us would prefer not to consider too deeply, just incase we fall short of the attributes necessary to not be too stupid. If the state of our Planet is anything to measure this by, then clearly we are failing to rise to the challenge of rational thought and must at some stage face the consequences. We are increasingly required to live, move, and consider events more quickly that we have ever done before, perhaps on a scale too broad for our brains to provide the necessary answers. Are we then too stupid to maintain our Planet in a liveable condition?… On the brink of a host of environmental catastrophes a rational thinker might say that it is certainly beginning to look as if we are, but we might also be on the brink of eliminating stupidity altogether… along with most everything else.

With thanks to Dr David Barlow for the use of his interesting picture of a human brain.

Part 2 to follow: ‘Beyond Rational Thinking’.

Who even thinks about the thought process that much. Where is the mind of someone who throws garbage out the car window or the coal mining executive who thinks climate change is a hoax? They toss their cans and wrappers, dig their mines but don’t consider the consequences, it’s a total disconnect in the thought process. Humans are experts at avoiding reality and moving on without any thought for the consequences. I suppose that disconnect is why the planet is hurting. Anyway, thanks for sharing your thoughts, sadly a discussion i’m sure a large section of the population would rather dismiss.

Reading Limitations of Experience was truly enlightening. Thanks

Thanks John. To be honest I don’t think a lot of us like to examine too closely why we believe what we do. All of us are bound by our genes and past experiences which help us to believe what we think we know is really true; and of course we all enjoy positive reinforcement when we get it.