An interesting photograph will sometimes push beyond the bounds of reason to the point where we should become skeptical, but deciding when we have moved beyond good sense and into the realms of gullibility is not always easy to assess; and this dividing line is important, because everyday we make decisions based upon images that throw into question exactly what we are prepared to believe.

When we pay for a service that relies solely on the written word, complexity is part of the deal. Buying into financial services or legal representation forces us to seek help, because these are disciplines that have evolved complex terminologies that usually benefit those doing the representing, ahead than those footing the bill. However, when a sale is direct – say from a supermarket shelf, simplicity is the key, and the fewer the words the better. Even more potent, is the use of visual imagery, which can grab our attention in a very physical way, or at least, that’s the way it feels. There is no doubt, that an appropriate picture can have enormous impact, even when presented through smoke and mirrors with the sole intention to deceive.

During waking hours we are forced to make hundreds of instant decisions about the ideas we will buy into and the ideas we won’t; much of this input comes directly from advertising, a medium full of contradictions where complexity and subtlety are often combined with a simplistic presentation that lures us in and then hooks our brains at a primeval level that can sometimes elicit a response more effectively than brain surgery.

A person extracted from a hundred years in the past and dumped into our modern world would at once suffer visual sensory overload, especially if they were forced to deal with the full compliment of technical gadgetry that has become part of our everyday lives, and yet most of us remain surprisingly unphased by this ever increasing complexity. At no time in history have we been more savvy or aware, and yet we are frequently confronted by images that raise serious questions about what we are prepared to believe.

In my mid-twenties I started making a film in the hope that it would help me get a job in television. Looking for an unusual subject I decided to work on my childhood preoccupation – reptiles and amphibians.

Whilst filming my chosen subject I was visited by a B.B.C. Natural History Unit producer with a background in outside broadcast -mostly covering golf. He told me that there would never be a successful film made about creatures such as frogs or snakes because nobody would want to watch it….. This was clearly a downer and I had a mind to ask, ‘Could there be anything less interesting than watching golf?’ but before I could drive home the point, David Attenborough’s ‘Life on Earth’ showed up and nothing would be the same in natural history film making again.

The producer of the amphibians programme, Richard Brock sought me out because he thought I might usefully film sequences for the amphibians programme, and he brought with him a far more positive attitude than his colleague. He was engaging as told me about ‘Frogs Law’, the gist of which is, amphibians are expressionless creatures that give little indication of when they are likely to do something, and only become animated when least expected. In consequence filming them can be very expensive. Sadly, I had already discovered this.

In the grand scheme of things my contribution to ‘Life on Earth’ would be small and initially revolve around the filming of British species, but I nevertheless put a great many hours into the project, mostly waiting for my cold blooded subjects to do something interesting. The film went on to become a favourite within the ‘Life on Earth” series and provided me with future opportunities to continue filming creatures that weren’t cuddly, hadn’t been filmed widely before and were of particular interest to me.

There were bad experiences of course, and I’ll never get back that week I spent trying to catch a female frog emitting her spawn… unfortunately I missed it, but there was a lot that I didn’t; it’s just unfortunate that I remember failure more clearly than I do success.

A by-product of half a lifetime of recording unusual animal activities is that I’ve spent more time watching, waiting and filming European common toads than I care to mention; and it would not be unreasonable to claim that for the most part, I know what these toads will do and even more useful, when they are likely to do it; and so much of their behaviour totters right at the edge of credulity. This then is my area of expertise and the one I have chosen to question visual believability. I could just as easily have chosen social insects – so be thankful I’m not going on about ants – I’Il stick with toads because they are bigger, slower and easier to photograph … But are they really slower, taking into account relative size? A question that has troubled me from an early age. I must have been an odd child, but fortunately, failed to recognise this at the time. Each of us has an area of expertise that provides us with our best possible chance to decide what is or is not true.

A hedge fund manager, might for example, be able to show us how to make money from something that doesn’t exist whilst staying out of prison – an activity right on the limits of understanding, even for the most perceptive amongst us. Of course, it can be done, but I can’t imagine how, and so it make sense for me to stick with the interesting but unlikely habits of Mr Toad. Why did the toad cross the road?

In early spring the urge to return to a pond (usually the pond of origin) is strong, and crossing a road is not something a toad is obliged to think much about. It just happens. When something moves across the retina of an amphibian’s eye neurons fire – a fast moving fly for example will stimulate a frog to flip out his tongue with great rapidity, whereas something moving more slowly may not elicit a response. Getting close to a frog or toad in the wild without disturbing it works on the same principle – you try to avoid firing neurons in the amphibian’s brain by moving slowly.

Frogs and toads react to stimuli without going through the trials and tribulations of thinking, although they have the ability to remember some things well, which rather gives the impression they are thoughtful creatures.

They orientate sometimes better than we can, and will usually move off in the same direction whenever they are replaced in an original starting position. You might believe that Mr Toad is decision making, but this is your illusion not Mr Toad’s – he’s not so much a thinker as a doer. You on the other hand have confused what you are prepared to believe with what you think you know. This is the story of our lives – thinking we know, and then believing what we think we know clearly isn’t the same as really knowing… but most of us just don’t know that. There is a lot going on in a toads head that we understand, but still a lot more that we don’t, and the ability to orientate is high on the ‘not yet quite understood’ list for both reptiles and amphibians.

Wouldn’t it be great if I had been prepared to lay on a road in the middle of the night and film common toads crossing… but of course, I never did. All of the central road shots were filmed on a set, and anytime toads were close to cars on a real road, the vehicles were driven by friends who knew exactly where the toads were, and when a toad got squashed it was always one made from plasticine. Sometimes it’s really difficult to know what to believe.

Amplexus is the action of a male frog or toad grasping a female, but with toads the whole thing can get out of hand when large numbers of males begin grasping a single female.

When common toads begin clinging on in numbers it is possible that a female will drown. At a time when these animals were far more common than they are today, I would wander around local ponds at night with a torch, and on finding a ball of toads would remove the smaller males that weren’t really in the game, and this would give the females a better chance of surviving (I know – interfering with nature!). Occasionally, I’d find a really large female that had drowned because she had been so laden with potential partners she was unable to surface for air – the ball rolls and males clustered around the female get to breath – It seems hardly fair, especially as the females, despite their age, are usually in good health – the selective advantage of the process is difficult to fathom.

Is it possible that toads become entombed in trees, only to be discovered when the tree is cut down. This isn’t as ridiculous as it sounds; once a toad finds a good hidey hole, he or she may sit in such a place for months feeding on passing prey, and eventually grow too big to squeeze back out. A toad might live for years like this, grabbing invertebrates that wander in, or catching those that pass close enough with a flick of the tongue. When the tree is cut the toad is startled into action by the activity; or perhaps when a tree is cut a nearby toad jumps and gives the impression that he or she has been liberated from a tight squeeze? It all depends on what you are prepared to believe based on the available evidence, or maybe by just using your own imagination.

And what’s the likelihood that a toad has a fitted air ride like some fancy hotrod. The answer of course is ‘close to zero’, that is until a grass snake comes by – and then a toad will do something that it never does at any other time.

You have more chance of being eaten by a python if you are lying down than when you are standing up. So on meeting a python more than twice my length, I always stand up. That makes good sense to me, but you can believe what you like.

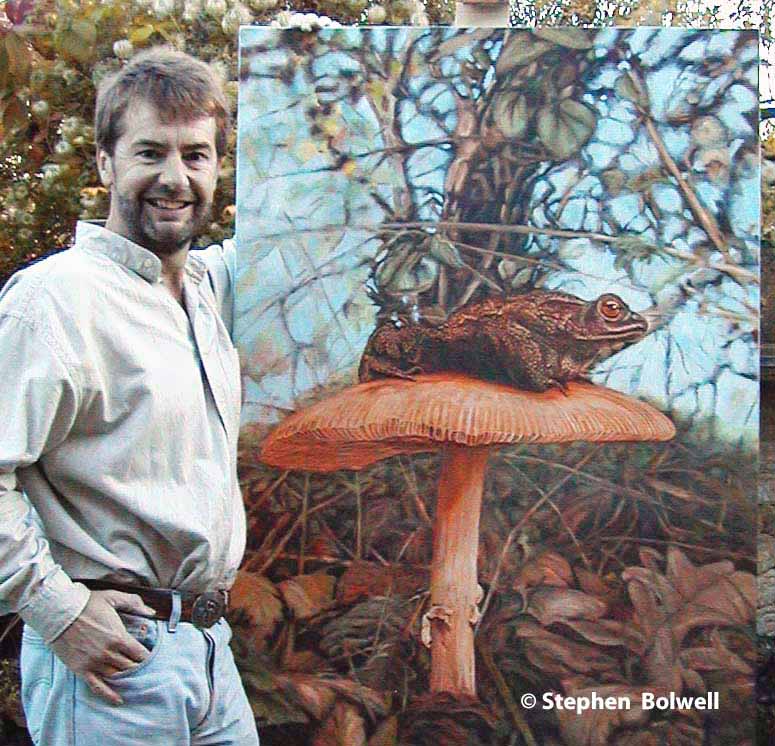

How did toadstools get their name? Surely it must be because toads hop up onto them. The obvious consideration is that a toadstool would be too weak to support a toad, but that’s not the case. The real question is, could a toad really manage to hop up there in the first place? Surely, it is more likely that those monkeys, given infinite time, will type the complete works of Shakespeare long before a toad manages this extraordinary leap – although for us, it just requires a leap of faith.

What if I was expecting a visit from a naturalist who had to come through a wood, and I placed several toads upon toadstools along his route – if he saw them sitting comfortably, would he consider the activity demonstrably proven? I once managed to get 7 toads onto toadstools before the first one started to get off – and a comfy toad might stay in place for several minutes.

O.K. That’s covered a few of the visual possibilities for toads – their response to movement and our response to what we see them doing. I guess we could start the whole story over again asking similar questions about auditory responses. How about ringing a bell to call Mr Toad out from his hole for a reward of food? Does that cross the borders of what is believable? If it is of any help… it doesn’t work with snakes (and that’s not because they’re stupid). Perhaps it would though… if we were prepared to jump up and down a bit.

What we find at the borders of believability, is always up to us.

Please remember that it is inadvisable to handle amphibians without good reason – their absorbent skins make them susceptible to disease – and in some cases it is now illegal to touch them.

Links below to two excellent and successful photographers who have assisted me in the past:

http://www.chrisbalcombe.com