On a recent trip to Belize, the mermaids – that would be my wife and daughter, sought out any excuse to immerse themselves in the Caribbean Sea; and my daughter’s desire to swim with a whale shark featured prominently on her list of reasons for our visit. It’s a rather hopeful wish on her part, but if you don’t think big there’s not much chance of experiencing anything out of the ordinary.

Alice had booked her place on an organised whale shark trip months in advance, and when the day arrives we all make the road trip to get her to the boat on time. Because our destination is some distance from our coastal base in Hopkins we are obliged to set off early in the morning, in darkness, before breakfast is served; this is a disappointment to me because I also have a list, but mine is of the things I no longer need to do – and missing breakfast isn’t on it.

I have never felt the need to swim alongside any kind of shark even when it is considered safe, and I won’t in any case be going into the water today because it would involve scuba diving – another thing on the list of things I don’t need to do. My wife Jen, can dive but she has been unwell and so it would be unwise for her to scuba; consequently, she will remain land based and keep me company.

Up at 5.30 a.m. we are soon driving southwards towards our destination – a dock in the village of Placencia, set at the end of a short peninsula that hugs the coastline for about 18 miles; but when we get there this turns out to be a very slow 18 miles – the entire road is plagued by speed humps set at regular intervals. There are various tourist hotel developments along the way, some have impressive gates, but these are mostly the sort of places we avoid because they are so out of keeping with their surroundings.

At the bottom end of the Peninsula the village of Placencia is altogether different – it is far more intimate than the impersonal hotels that we passed on the way; it is busy with local people and has several agreeable places to eat. A huge surprise though to pass an airport just before we arrive, which initially seems out of place. Until recently this destination must have been close to the back end of nowhere; but the holiday business is rapidly changing that.

At the bottom end of the Peninsula the village of Placencia is altogether different – it is far more intimate than the impersonal hotels that we passed on the way; it is busy with local people and has several agreeable places to eat. A huge surprise though to pass an airport just before we arrive, which initially seems out of place. Until recently this destination must have been close to the back end of nowhere; but the holiday business is rapidly changing that.

I can’t think of a better way for the wealthy to avoid the speed bumps than to fly in; certainly it is the quickest way in. As a wealthy person once said to me, ‘I can always earn more money, but I can’t buy more time’… And I guess that’s fair enough, but above all else, what they are really interested in buying here is real estate… and lots of it.

It is a bright sunny morning and we arrive early enough to go for breakfast in a local cafe, although the waitress is quite unhelpful; there’s a lot we can’t have from the menu because it’s too early and she hasn’t had a chance to shop for fruit and vegetables; unfortunately she doesn’t explain this and we waste a lot of time asking for things that are unavailable. It’s as if we are taking part in an unfunny version of ‘The Monty Python’ cheese sketch. ‘Mango this’… No. ‘Banana that’… No. ‘A veggie omelette’…. No. ‘Orange juice”….Ummm… No… We eventually hit on a few things that the kitchen does have, mainly choices that revolve around cakes and pancakes, unhealthy stuff, but great when your earlier breakfast never happened.

Unfortunately, the food takes so long, we are made late by the waiting and should have left by the time it arrives. We gulp it down, and have trouble getting the bill because our waitress seems to be moving through ‘treacle time’. We finally pay up, dash to the nearby dock, and despite the delay make it in time.

Alice will be out at sea for several hours, leaving Jen and I plenty of time to drive back up the peninsula and take a look at the coastal environment. The eastern seaward side is mostly sandy beach of the type popular with holidaymakers – but there are also stretches of mangrove less favoured by tourists; nevertheless, mangrove is an essential habitat that acts as a nursery for creatures that will eventually live out their lives on nearby offshore reefs.

We then travel along the western inner arm to search out the mangrove that borders the narrow bay adjacent to the Caribbean. Clearly, the mangroves were once extensive here, but are now intermittent and are being overtaken by development.

Indifference to mangrove destruction doesn’t make sense, but it is a widespread problem. On October 8th 2001 Hurricane Iris hit this area and levelled around 95% of Placencia – a hurricane can do this almost anywhere, but when the weather is just bad rather than extreme, mangroves offer at least some protection to things that you hope might stay attached to the land when things get rough.

Mangrove destruction is now a common problem in warm coastal areas where holiday developments are becoming widespread and the suggestion that building resorts is good for local economies doesn’t always work out as well as it might. Often the process involves rapid changes to the coastlines, and essentially too much happens too quickly. When multinational companies are involved they often prefer to bring in their own workforce, leaving the locals with only the most poorly paid and menial tasks; and there is often a disinclination to train local people to provide them with better opportunities.

When developments are rapid and extensive, habitats that local people have relied upon for generations are often quickly degraded, and it isn’t greatly appreciated when wealthy outsiders (who don’t need the food) arrive to ‘sports’ fish valuable natural resources. When financial gains don’t filter through to people living in the area, resentment grows, and when much of the profit goes offshore there may be no longterm benefits to local communities. Few visitors choose to notice this problem because to do so would mean leaving the hotel to speak to locals who will furnish a broader picture – something almost unthinkable. Certainly there are dangerous places around the world, but it is irrational to be frightened of moving amongst locals in the places we visit – it’s madness to behave like prisoners locked in holiday complexes that provide everything we need but reality.

When developments are rapid and extensive, habitats that local people have relied upon for generations are often quickly degraded, and it isn’t greatly appreciated when wealthy outsiders (who don’t need the food) arrive to ‘sports’ fish valuable natural resources. When financial gains don’t filter through to people living in the area, resentment grows, and when much of the profit goes offshore there may be no longterm benefits to local communities. Few visitors choose to notice this problem because to do so would mean leaving the hotel to speak to locals who will furnish a broader picture – something almost unthinkable. Certainly there are dangerous places around the world, but it is irrational to be frightened of moving amongst locals in the places we visit – it’s madness to behave like prisoners locked in holiday complexes that provide everything we need but reality.

It would of course be wrong to imply there are no benefits to previously isolated communities when they are suddenly transformed by tourism, but it is noticeable – if you care to look – that many people remain in poverty while the profits go elsewhere. This results in a very one sided spin on the benefits that tourism can bring to poor communities. Clearly there are advantages when outside money is brought in, but the amount that filters through to local people is often meagre and many will see no benefits at all.

What nature provides in far away places is often taken as freely available and without consequences, but as holiday based economies continue to expand, it is increasingly evident that there can be no free lunch; someone local will be losing out to pay for the good fortune of the many visitors arriving from elsewhere, and investors will continue to make big bucks by exploiting environmentally sensitive areas.

If big hotels and cruise liners continue to feature in fragile environments and during the process they reduce air and water quality, it might be worth asking whether such problems outweight the often one-sided financial gains…

I know! who wants to think about this kind of thing when you’re on holiday, or fortunate enough to be on the right side of what is rapidly becoming a gaping economic divide; nonetheless this is a reality that can’t be ignored forever.

We saw the last 5 acre ‘investment opportunity’ (as it was described by one realtor) up for sale on a board in Placencia village. We could find no evidence to suggest that many here thought it necessary to retain the mangroves, and it appears that it won’t be long before most of this peninsula will be developed in one form or another, with this important habitat degraded or perhaps entirely lost… And who will remember once it has gone?

Much of the development along the coastal area where we are staying and where we started out this morning – in Hopkins – is paid for with American dollars and many who come to visit these newly developed areas are Americans.

From an environmental perspective mass development of coastal regions isn’t really a great idea. I love the Americas in particular, but feel as if I need a shower whenever I touch an American dollar. In common with nearly all the paper money you handle in warm countries it is often badly worn and it usually stinks. Perhaps the money itself is trying to tell us something.

Coastal Belize is much favoured by tourists from Texas and the village of Hopkins is about to be turned into a major tourist spot.

Presently the Belize road system is quite variable, with some sections very rough; the drive to Hopkins from Belize City Airport really isn’t much fun because you are always on the look out for potholes and speed humps. The last part of the journey up through the village is especially rough; at the time of writing it is no more than a dusty track peppered with potholes, but this is about to change as a new blacktop road is planned and by the time you are reading this, it might already be in place.

Many of the locals don’t feel comfortable with the new developments as they won’t themselves be seeing much in the way of profit from the upgrades. Despite the sudden influx of money, conditions for many have not, so far, greatly improved and many people’s lives may not change very much despite the fact that a holiday in Belize isn’t a cheap option. This kind of ‘progress’ where money flows in but nothing much changes on the street isn’t in any sense fair… But it is what it is.

Hopkins might still run along a dusty track, but every child has a place in school which must bode well for the future of Belize… if the whole country doesn’t eventually get bought up by outsiders.

All things considered, it isn’t difficult to understand why the money that is flowing into places like Hopkins and Placencia isn’t filtering through to the average person. Everything changes when markets go global and the consequences of such rapid development is the cause of much bad feeling.

An airport is soon to be built close by Hopkins and this along with the road upgrade, explains why land speculation has gone through the roof. It is a huge problem, because as outsiders speculate, local people are priced out of the market and suddenly out of the equation.

Back around Placencia we wander

along what remains of the mangrove, much of which is likely to disappear as holiday developments begin to pick up apace; but for the moment what remains of this habitat adds an air of mystery to the coastline, particularly from the seaward side, where you can’t help but wonder what lies beyond them.

It is a hot afternoon as Jen and I walk back to the dock to wait for Alice’s boat to re-appear on the horizon. There was a slight breeze this morning which caused a surface ripple across the water, but all is now still, allowing me to take pictures of seahorses amongst the seagrass just off the dock. In the past I’ve worked with captive seahorses in my studio for the B.B.C. which was much easier. Not so much for Jen though because she was the one looking after them. Keeping seahorses healthy in captivity can be labour intensive and requires considerable skill – so don’t even think about it!

Getting a clear shot in this natural setting is far less easy but it is at least ethical. With so much pressure on seahorse habitat now, and the annual trade (particularly in south-east Asia) in millions of these wonderful animals for their erroneous medicinal value, has pushed many of the 50 plus species that we presently know of into general decline.

It isn’t long before Alice’s dive group arrives back, but there is an air of gloom hanging over the boat. No whale sharks were seen and further research on our part suggests that there have been no reliable sightings by dive groups in local waters for at least two years. One whale shark diving concern recently changed the description of its outings because of this, while others are still trading as whale shark tours; it maybe that the only sharks around here are tour operators. When you dive in the sea, nothing is guaranteed, but to advertise a tour specifically using an animal’s name when there are no representatives in the area is nothing short of deceitful.

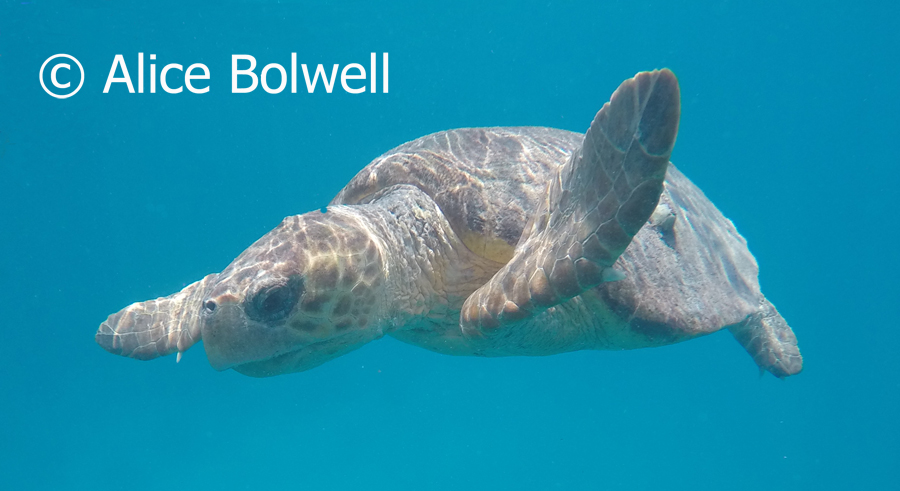

Alice’s loggerhead turtle pictures turned out rather well, but one in particular stands out because it could prove useful as a future means of identification. I have spent much of my photographic career trying to take pleasing pictures of wildlife and for most of my working life have made a living from it; but in truth, apart from making me feel I’ve achieved something personally… what is the use of it? There are plenty of good pictures of turtles, but one that provides reliable identification rather than just a pretty picture could prove far more consequential.

A simple picture from above shows the pattern of the plates or ‘scutes’ on the turtle’s shell, as well as the scales on top of the head; the number and shape of these can provide a reliable means of species identification and when combined with wear and tear body markings may also indicate particular individuals. Certainly when accompanied by a date and location, a record of these patterns can have considerable scientific value.

In the end, the natural wonders of Belize may prove to be a bit like its plumbing in that there are many things here that are resilient to being flushed away, but as the outside world brings with it greater expectations – and a flush of money besides, it may be that almost anything can be sent swirling down the pan. One must hope for better things for this beautiful place, but only time will tell.