The Hawaiian Islands were formed in the middle of the Pacific Ocean by tumultuous volcanic activity – this is still happening and is presently centred on the Big Island, Hawai’i. Mt Kilauea on the south-east side of this island remains active and has been spewing lava almost continuously since 1984. Put simply, Hawaii is moving steadily over a hot spot that lies beneath the Pacific Plate.

To the west and more central to the island is the volcanic mass of Mauna Loa which rises just short of 13,700 feet; it has erupted only twice since 1950: once in 1975 for a day, and again in 1984 for three weeks. At the moment things are quiet, but it is still considered the most active volcano of recent time, having erupted 33 times since its first historical eruption in 1833. Not far away to the north across a saddle of lava stands the sister peak of Mauna Kea – presently dormant it rises to nearly 14,000 feet above sea level and I was fortunate enough to travel up it quite recently – this sounds impressive, but getting there is a doddle because you can drive more or less all the way. It is however the toughest road journey anywhere in the world should you choose to do it on a bicycle!

To the west and more central to the island is the volcanic mass of Mauna Loa which rises just short of 13,700 feet; it has erupted only twice since 1950: once in 1975 for a day, and again in 1984 for three weeks. At the moment things are quiet, but it is still considered the most active volcano of recent time, having erupted 33 times since its first historical eruption in 1833. Not far away to the north across a saddle of lava stands the sister peak of Mauna Kea – presently dormant it rises to nearly 14,000 feet above sea level and I was fortunate enough to travel up it quite recently – this sounds impressive, but getting there is a doddle because you can drive more or less all the way. It is however the toughest road journey anywhere in the world should you choose to do it on a bicycle!

Of greater interest perhaps is that the slopes of these impressive volcanoes provide a variety of habitats entirely determined by changes in altitude. The most obvious way to experience climatic change is to travel from the equator to polar regions, which takes time and money, but there is an alternative: go to Hawai’i and ascend either Mauna Loa or Mauna Kea and experience similar changes over a much shorter distance.

A few weeks ago my friend David Barlow and I did exactly this, driving from sea level to within a few feet of the summit of Mauna Kea, on the way rising through a variety of different habitat types to arrive above the tree line in a very short journey time: from a tropical beach to a stark arid landscape in a matter of hours, experiencing changes that were both marked and abrupt – and I was able to make a visual record of species before we returned to sea level in less than twelve hours without rushing about.

The first bird of the day showed up during breakfast – a member of a flock that was picking off grass seeds on the lawn behind our apartment. Introduced from South America in the 1960s this attractive bird is now well established.

The first bird of the day showed up during breakfast – a member of a flock that was picking off grass seeds on the lawn behind our apartment. Introduced from South America in the 1960s this attractive bird is now well established.

We then took a short walk to the beach and along the track saw a red cardinal in a non-native acacia tree. This bird was introduced to the islands in the late 1920’s from the Eastern States of North America; it has a formidable beak essentially for seed eater, but this colourful creature will take insects and other small animals, putting it into direct competition with native birds, or would, if there were any about! Almost nothing endemic exists at sea level apart from the occasional sea bird – a shocking situation that usually passes without comment. Few people realise the birds they see are recent introductions, and no tourist operator would break the mood by broadcasting that at lower altitudes, the most commonly seen creatures are as alien to these islands as snow at Christmas.

We then took a short walk to the beach and along the track saw a red cardinal in a non-native acacia tree. This bird was introduced to the islands in the late 1920’s from the Eastern States of North America; it has a formidable beak essentially for seed eater, but this colourful creature will take insects and other small animals, putting it into direct competition with native birds, or would, if there were any about! Almost nothing endemic exists at sea level apart from the occasional sea bird – a shocking situation that usually passes without comment. Few people realise the birds they see are recent introductions, and no tourist operator would break the mood by broadcasting that at lower altitudes, the most commonly seen creatures are as alien to these islands as snow at Christmas.

The yellow-billed cardinal is also common, it was introduced from South America in the early 1970s and is spreading. These birds occur mostly at lower altitudes, but have been seen more recently at around 6,000 feet where they come into contact with endemic species; this causes not only straight competition, but the possibility of spreading diseases such as bird malaria which the natives have no tolerance of.

The yellow-billed cardinal is also common, it was introduced from South America in the early 1970s and is spreading. These birds occur mostly at lower altitudes, but have been seen more recently at around 6,000 feet where they come into contact with endemic species; this causes not only straight competition, but the possibility of spreading diseases such as bird malaria which the natives have no tolerance of.

Continuing on to the beach we came across a beautiful but nevertheless non-native tree under which a silver eye was feeding two fledgling youngsters. I know this bird well because it was often in our New Zealand garden, although it originates from the opposite end of the Pacific; the NZ version arrived from Australia sometime during the 19th Century, and this version is from Japan.

The Hawai’i white eye was introduced in the late 1920s; it is an agreeable song bird and an absolute sweetie, but like the yellow-billed cardinal, has spread to higher altitudes where it too competes with native birds. White-eyes are opportunistic feeders and as nectar makes up part of their diet this puts it in direct competition with native honeycreepers that have evolved on the Hawaiian Islands and can be found nowhere else. Back in its homeland this is a delightful bird, but on Hawai’i it is becoming a problem.

One animal that seems to be everywhere at lower altitudes is the Indian mongoose, particularly where there is broken lava flow that provides this efficient little predator with ideal hiding places. This seems an odd choice for an introduction because the Hawaiian Islands have many delicate ecosystems that until recently were totally devoid of mammalian predators.

One animal that seems to be everywhere at lower altitudes is the Indian mongoose, particularly where there is broken lava flow that provides this efficient little predator with ideal hiding places. This seems an odd choice for an introduction because the Hawaiian Islands have many delicate ecosystems that until recently were totally devoid of mammalian predators.

This less than ideal newcomer was introduced in the 1880s to take on the rat population so prevalent on sugar plantations. As rats are nocturnal and the mongoose diurnal the two seldom met, and together worked around the clock consuming Hawai’i’s native birds – in particular the ground nesters. It is claimed that the mongoose is responsible for the elimination of at least 6 native species from these Islands.

I could continue working through a list of all the beautiful plants, butterflies and birds around where we are staying that are clearly non-natives, but if I did, we wouldn’t get much beyond the car park — so it has to be onward and upward.

David and I began our drive to altitude by crossing the island using Route 200, or the Saddle Road as it is commonly known. This runs between the two volcanic masses of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, and as regards native species, we saw nothing until we got to around 6,000 feet.

At these higher altitudes in national park areas, plants appear very different from the exotic introductions commonplace at sea level. There were similarities to my New Zealand experience, with many native plants carrying smaller, more subtle flowers that many of us ignore in preference to bigger blousier forms that are easily introduced…. But what the heck, people just love dressing up their islands the way they decorate their Christmas trees — with exotic colourful tat that makes them feel more cheerful. Perhaps if we were better informed we might be inclined to consider our native plants more sympathetically, but the chances are… we probably wouldn’t.

It is tempting to suggest species evolving on islands are delicate, but the reality is, most are well adapted to their surroundings, otherwise they wouldn’t have survived. It is only when rapid changes occur that natives are found wanting, as was the case when Homo sapiens arrived on the Islands — adaptation through natural selection simply couldn’t equip the natives quickly enough to allow them to compete successfully with the many introduced pests they encountered.

Just before turning off to Moana Loa we stopped to visit Hairy Hill on the opposite side of the road. It was a gentle walk up the old cinder cone that rises just a couple of hundred feet, providing enough height to survive a more recent lava flow that obliterated the flora of the surrounding area; what remains is a reservoir for native plants and trees, and amongst them there is a pleasant ambiance to the small isolated mossy forest that exists near the top, although moss is not be a surprise here because the area is often swathed in dank mists, imbibing the open lava flow below with a certain atmosphere – and it is no wonder that such places have spiritual significance for native people.

On the opposite side of the road John Burns Way leads us up towards the summit of Mauna Kea. We stopped just short of the point where the tree line changed abruptly into a high altitude desert to emerge from cloud cover into bright sunlight. I pulled the car off the road at 9,000 feet so that we might acclimatise to the altitude; but had an ulterior motive: I’d hoped to photograph native birds in the area, but this would depend entirely on finding plants carrying nectar filled flowers to attract them in, otherwise we could search all afternoon and perhaps see birds only fleetingly. There is little to be gained by chasing wildlife about – if there was nothing to draw birds in to where I could stand quietly, the chances of getting worthwhile images was slim.

We start searching on foot and it is at once clear that a great many unwanted plants have been introduced here, some accidentally; and eliminating them is likely to be an ongoing problem for park authorities. In fact, the weeds are so numerous and producing such copious amounts of seed, it might be a case of ‘know your enemy’ and prioritise those that are competing most harmfully with native species.

There was no shortage of Common Mullien Verbascum thapsus, originally brought to North America by settlers from Europe for medicinal purposes. It has now reached Hawaii and doing well at altitude on Mauna Kea.

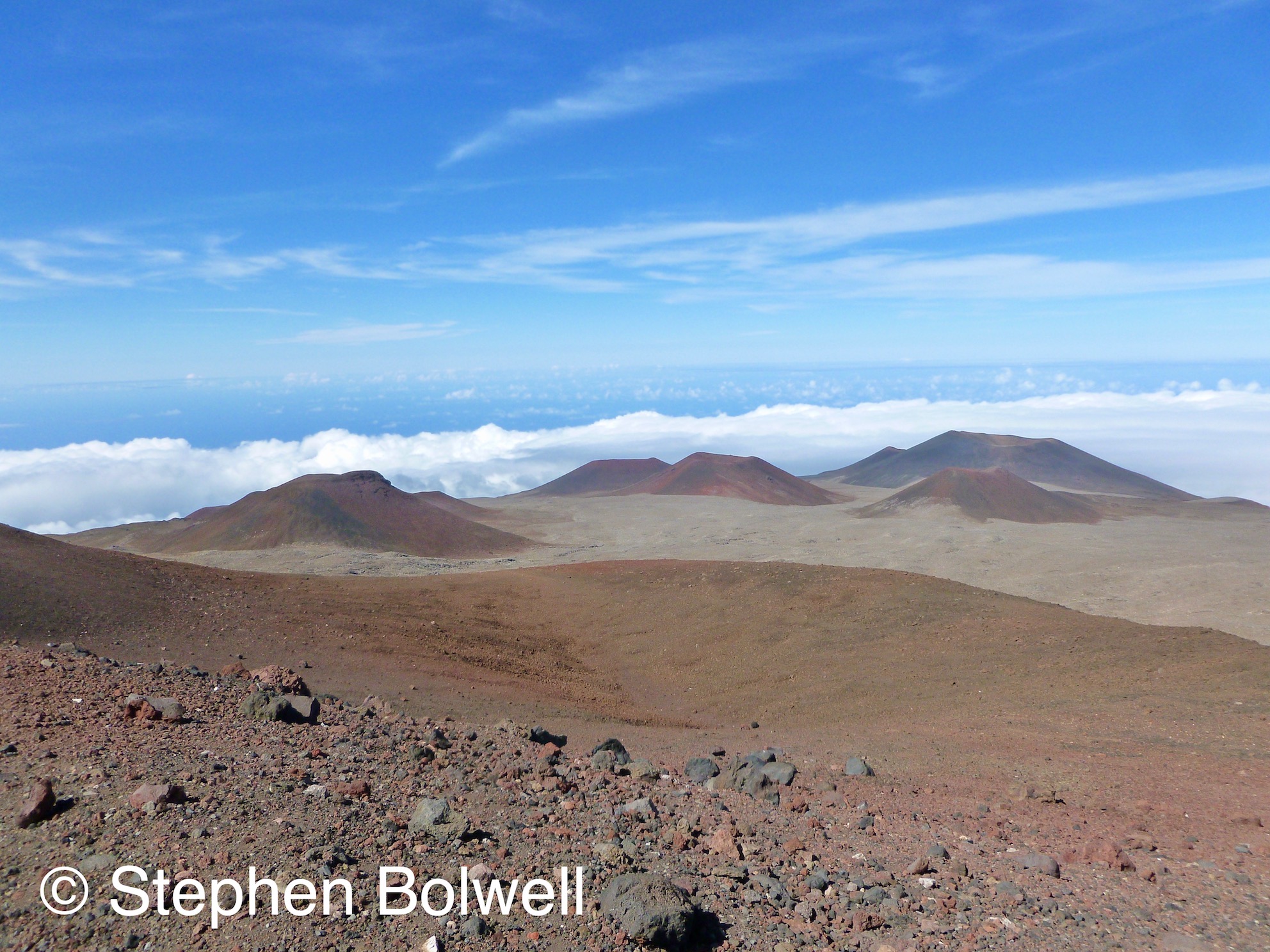

This volcanic mass we are on is the tallest mountain on the planet, but not recognised as such because the height of a land mass is always taken from sea level to provide a standard for the measurement of altitude. However, if Mauna Kea was measured from the ocean floor it rises to around 33,000 feet and there is nothing on Earth that will match it – apart from the peak we can see across the saddle in front of us — that of Mauna Loa, which is around a 100 feet short of the volcano we are standing on.

To have two such massive features on an island that takes only a couple of hours to cross is remarkable. Everest is considered the highest mountain in the world at just over 29,000 feet it is part of the Himalayas – a mountain chain that pushed up like a rucked carpet when two continents collided: 50 million years ago the India plate started crashing into the Euro Asia plate and they continue to do so; but the Hawaiian peaks are perhaps even more impressive, thrusting as they do from the ocean floor driven entirely by the dynamism of volcanic activity.

It doesn’t take long to see a yellow flower, a member of the pea family, that is similar to the kowhai flower that I know from my time in New Zealand, which demonstrates that the relatedness of some plants can be clearly followed across the Pacific region, although how this member of the Sophora family arrived in Hawai’i remains a mystery.

The blooms I set up on hung from a mamane tree, a species integral to the upland forests of Hawai’i with flowers drooping down seductively from a canopy that can reach up to 50 feet. Unfortunately, the tree’s survival on the Hawaiian Islands has not been plain sailing: prior to and during the 1980s the upland slopes of Mauna Kea were ravaged by introduced grazers, and legal action was taken against the government at both local and federal level on behalf of two bird species. The resultant court case ended with a win for the endangered birds, in particular the Palila (Loxioides bailleui), a honeycreeper that relies heavily on Mamane tree seeds for food, as do caterpillars of the Cydia moth which also feed on the young seeds of this tree and the birds in turn feed on them. Both bird and insect must avoid the mature seed coats because they are highly toxic, although these animals have developed a degree of tolerance to the alkaloid poisons that are present. It appears the fauna remains just ahead of the flora in this evolutionary arms race and having gained the advantage, utilise the mamane seeds as an essential part of their diet.

As for the other battle – the legal one: on paper it was clearly a win for the birds and the environment, but in reality this wasn’t absolute. Soon after the judgement sheep and feral goats that for years had been decimating the upland forests were at last being removed, but the court order was never fully complied with until another court order was made in 2013 backing the protective measure, and renewing efforts to remove the pests that were pushing the Palila bird in particular to extinction. I am not certain of how successful this has been, but we at least didn’t see any alien grazers during our visit.

This is just one of a host of conservation issues that plague delicate island environments. Conservationists and volunteers do their best, but pest problems are frequently overwhelming, and there is usually a struggle for adequate funding.

The Sophora flowers blooming on Mauna Kea are as important to the native nectar feeding birds of Hawaii as the related kowhai flowers are to the tuis and bellbirds that regularly visited the trees we had planted in our New Zealand garden. Understanding such alliances is important and may prove instrumental in both protecting and bringing associated species together.

Back on the mountain I stood in the mid-day sun waiting… and it wasn’t long before a small bird came flying in to my chosen tree, but it was soon away with a dipping up and down flight that is probably peculiar to its species. I was pretty well set up by then and hopeful of a return visit – although this was not an entirely pleasurable experience, as standing in the sun at altitude with increased levels of UV will quickly sear exposed skin.

The bird made three further visits at approximately twenty to thirty minute intervals and remained completely untroubled by my presence. The little nectar feeder spent three or four minutes feeding on groups of flowers before flying off to presumably visit other flowers in the area; certainly it flew some distance beyond a point where I could see it, which suggested that it was feeding over a fairly wide range.

After a couple of hours acclimatisation we had achieved all that was possible and continued on to the summit. Almost at once we were on Mars, albeit a Mars with blue skies and genuine atmosphere; but the views were not as spectacular here as the Mars-scapes I’d previously seen near the summit of Haleakala which rises to just under 10,000 feet on the neighbouring island of Maui. From our vantage point we could at least see Haleakala coming and going some 35 miles away as clouds moved across the substantial peaks of both islands. Now close to the 14,000 foot summit David framed the view and set his time lapse in motion.

I finished my photography fairly quickly – because wildlife opportunities are limited at this altitude – and was just admiring the view when David arrived with a young lady he had found, he left her with me and returned to his camera— the altitude had got the better of her, although her boyfriend had fared better and decided to walk back down to the visitors centre from where they had started out. David had agreed that we would drive his girlfriend down because of her condition. I sat her on the back seat of our car amongst the gear and told her how lucky I had been to photograph a honeyeater, but she seemed disinterested, obviously she wasn’t big on wildlife and so I stopped talking, at which point she shot out of the car and began projectile vomiting in a quite spectacular manner… I must admit that I did think about taking a photograph, but refrained from doing so.

Soon back in the car she began telling me how much better she was feeling. I smiled and nodded encouragingly and at once she took a turn for the worse and did it all over again. Hopefully it wasn’t the company she was keeping… more likely, having taken a meandering walk up in 40% less oxygen than there is at sea level and going that little bit further to the summit she had developed altitude sickness. It was clear that we needed to get her to a lower altitude as quickly as possible and so David’s time lapse came to an abrupt end and I was soon driving us towards the visitors centre considerably faster than when we had made our way up – thinking all the time that a four wheel drive would have now been quite useful. The dirt road had been rutted and tricky to negotiate on the ascent and I had driven slowly to look after the vehicle, but on the way down it was a different story.

We were going quite fast — why wasn’t I sliding us off of the volcano? Then, it suddenly occurred to me — the grader I had noticed parked close by the visitors centre had been doing its job at an opportune moment and the track had been graded all the way to the top.

Half way to our destination, away in the distance Kilauea had a little spew of her own – signalling that tomorrow would be another murky VOG sky day, even on the other side of the island.

Hawai’i it seemed was presently troubled by one of it’s little volcanic phases, but sadly the island also displays a good many environmental problems concerning the preservation of its endemic species… Nevertheless, even a true story should have a happy ending – so here it is. The girl and the volcano have stopped spewing now and both are doing fine.

There is also a moral to this story: a little bird recently told me that we all spend too much time obsessing over how beautiful things are, rather than how beautifully things fit together. Unfortunately, the latter requires far greater imagination and understanding than does the former, and more often than not, like many a good mixing of metaphors, we sometimes find ourselves on the right volcano, but chirping up the wrong tree.

I started the day with a little yellow bird that doesn’t belong, but didn’t manage to finish with the Palila – the yellow-headed bird that does – it was just too hopeful. Science has informed us quite thoroughly of what this rarity requires, and in that sense the tricky work has been done, but the will to save this beauty from extinction may simply not be there. And the way things are going – in the natural world at least – happy endings are increasingly difficult to find.

Stephen, I love the pictures of Hawaii! Makes me feel like I’m back at home. Seems like you had an amazing time on the islands.