Given the many problems caused by humans to the various species living on Pacific Islands, their rapid decline seems inevitable, but to a degree this process was happening naturally, long before we showed up. Such losses and gains were, and still are, dependent upon many factors, but as a general rule, smaller islands exhibit a greater turn over than do larger islands; and the arrival of man has now pushed the losses to the level of a major extinction event, with both New Zealand and Hawaii exhibiting clear examples of the problem.

I mentioned Hawaii’s carnivorous caterpillars in a previous article, and do so again because they are such a great example of the unusual directions that evolution can take on islands largely isolated by distance. So far as we know, meat eating caterpillars occur only on the islands of Hawaii.

How plants and animals get to be on a remote island in the first place depends on several things: the size and topography of the island, and its position in relation to other nearby islands is important; as is the distance these islands are from major land areas that might act as starting points for new arrivals, and this is critical both to what will arrive and how frequently; any organism capable of parthenogenesis (the development of embryos without the need for fertilisation) will have a better chance of getting started than will animals that require both males and females for reproduction.

Each and every island has a unique story held in its geology. Consider Australasia – around a 100 million years ago this huge land mass separated from Godwana (which was at the time a supercontinent). The split from Antartica happened between 37 and 35 million years ago as it moved northward. The land that would eventually be New Zealand started moving away from the larger mass we now call Australia between 60 to 85 million years ago.

It is possible that NZ once formed part of a drowned continent, but for the millions of years the two main islands have remained above water in one form or another, extensive changes have occurred — including climatic extremes which will have eliminated many life forms.

Initially, when New Zealand sat alongside Australia, both were set in the same sub-tropical waters and in consequence had similar floras, but as the two separated, the sea flooded into the rift between them and formed the Tasman Sea. In consequence the New Zealand flora became isolated and new species began to evolve.

For the last 55 million years N.Z. has held its current position at around 2,000 kilometres to the south-east of Australia and experiences a much cooler climate than it once did, but ironically it now appears to be moving slowly back.

A lot can happen in 55 million years and the fine detail will always remain uncertain, but nevertheless there is clear evidence that a great many species have come and gone during that period with most of the present New Zealand species of recent origin.

Apart from a few marine mammals and a couple of bat species, no other mammals have survived on these islands;

and none managed to colonise successfully until the arrival of Polynesian settlers less than a thousand years ago; this was followed by a second wave of mammalian competitors that came along with Europeans when they began settling little more than 250 years ago, with dire consequences to the established native species.

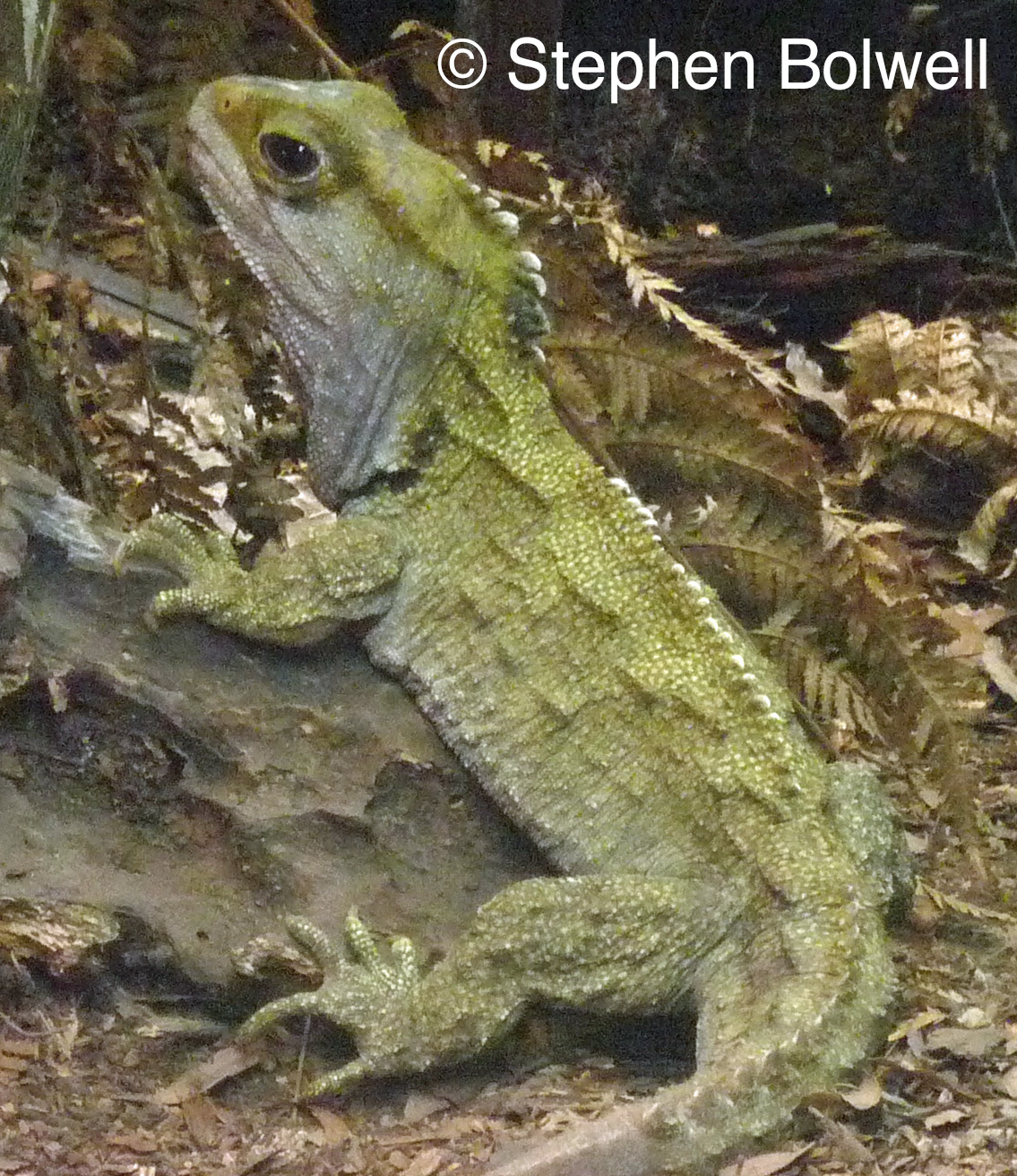

Prior to the arrival of humans and their entourage of plants and animals, New Zealand had been populated by a very distinctive flora and fauna that developed in isolation of the many mammalian predators evolved elsewhere. A European botanist arriving for the first time might initially consider that they had landed on another planet, because the invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles and birds that fill the niches taken up by mammals elsewhere, are so extraordinary.

New Zealand has been around for some time, but the Hawaiian Islands were formed far more recently and exclusively by volcanic activity — they quite literally erupted from the depths of the mid-Pacific and are about as remote from any other land area as it is possible to be. The first island, Kaui, started to push above water around 5 to 6 million years ago and is now the most westerly island in the chain. To the east at the opposite end is the Big Island (Hawai’i), and at less than a million years of age is still volcanically active.

Hawai’i is not huge, but nevertheless, it is big in comparison with the other islands in the chain. At around 10,500 square kilometres it is larger than the rest of the Hawaiian Islands put together, making up more than 60% of their total landmass.

Once the islands were formed, the possibility of a new plant or animal arriving on these tiny specks in the Pacific Ocean became a lottery. Miss the islands by only one mile or by a thousand, and the result would be the same — oblivion. Small organisms produced in large numbers will have had the best chance of arriving, with spores, seeds and tiny creatures the most likely candidates to be carried successfully on mid-altitude air currents to land against the odds on distant islands, although most of course will have perished.

Some species might have arrived carried across the surface of the ocean on any material that could stay afloat long enough to make landfall, but again the attrition rate would have been high and the chances of success slim.

It was a long shot that birds would arrive on Hawaiian Islands at all, given the distances involved, but when it did happen they would most likely have been carried on mid-altitude air currents. It is quite possible that only one or a small number of finch species arrived to become the honey creepers that radiated out across the Islands filling different habitats as they evolved into the 56 species that have been recorded, 18 of which are now extinct.

This article links: The Down Side of Remote Pacific Islands – The Disappearing Species of New Zealand. and: The Down Side of Remote Pacific Islands – The Disappearing Species of Hawai’i.