Pre-covid, but not so long ago, Jen and I took a trip to Manning Park in British Columbia intending to visit upland meadows in full flower; but you know how it is with the natural world — get your timing out by a week one way or the other, and you’re either too early and there’s nothing to see, or you’re too late and everything’s gone to seed. It’s a bit like life really — there are plenty of opportunities to miss.

Living on the coast as we do, the time schedule for many natural events runs seasonally ahead of events further inland. The nearer to the sea, the more temperate and mild it is. Go north (or in the Southern Hemisphere, south), or anywhere where altitude increases and natural events are playing catch up. In the case of Manning Park not only did we travel inland across a great land-mass, but we also rose well above sea-level, consequently the upland meadows hadn’t quite reached their best; but when you’ve come a distance, you’re duty bound to find something interesting. In our case it was ground squirrels; and not just because they’re cute; there was also a good story.

But before we got acquainted with the local rodents; we would need to deal with the disappointment of what we wouldn’t be seeing — a delightful expanse of upland meadows with colourful flowers waving in the wind.

A trip to the visitors centre is always the best place to start when a park is new to you and there we obtained a map marked with flower meadow locations and set off to see them; but not before I’d asked the pleasant park official if there had been any recent bear sightings? She said she had never seen a bear in the park, and I responded by saying, “You need to get out more.” The kind of remark that is better thought than said in these enlightened times when to say almost anything can cause offence. I must try harder, or failing that, stop leaving the house. Fortunately, this is Canada, and the woman concerned wasn’t the least offended; either because Canadians are such polite people, or because you have to say everything twice to be sure they are listening… I notice the hole I am digging is getting deeper…

Very soon we parked up close by an alpine meadow, and before we’d walked 20 metres a couple emerging from a nearby trail told us there was a black bear on the corner, but by the time we arrived the bear had moved on — bears having the advantage over plants by not being rooted to the spot.

Bear free we inspected the meadows more closely. There were certainly flowers and insects to photograph, but the general paucity of flowers encouraged us to move on to a nearby beaver pond because the presence of fresh water always ups the chances of seeing something interesting.

Adding another habitat type invariably increases diversity, and water is exceptional at increasing the species count and the effect can be very noticeable.

We soon come across a rein orchid Platanthera dilatata which prefers boggy upland conditions, along with a dragonfly we don’t so often see on The Lower Mainland.

I’m probably the only person happy enough to trade a bear sighting for a dragonfly, especially if it’s a species I don’t regularly see — for some reason I find these extraordinary insects more interesting than bears and there’s no shortage of them here and a great many are rattling around. We take time to photograph any individual that land close by; and the calmness of the open water encourages us to spend more time by the pond than we might have done.

We spend a pleasant hour observing creatures that haven’t changed much since before the time of the dinosaurs, although some dragonflies during the Carboniferous Period were far larger than those flying around us today, back then the oxygen content of the atmosphere was higher, allowing them to supersize. Thankfully the ones landing on us are far smaller and less terrifying than would have been the case in a similar boggy conditions 350 million years ago. Once the novelty of being perched on by these harmless little predators had worn off, we returned to the vehicle.

We spend a pleasant hour observing creatures that haven’t changed much since before the time of the dinosaurs, although some dragonflies during the Carboniferous Period were far larger than those flying around us today, back then the oxygen content of the atmosphere was higher, allowing them to supersize. Thankfully the ones landing on us are far smaller and less terrifying than would have been the case in a similar boggy conditions 350 million years ago. Once the novelty of being perched on by these harmless little predators had worn off, we returned to the vehicle.

Entering the car park there was a scurry at my feet. Such an event would usually be a disappointment where we come from, indicating the presence of a rat, but this particular scurry was far too delicate. We sat in the car and ate our lunch, in the hope that the scurrier might return; and it did so almost before I’d had time to get the lid off my sandwiches. The rapid response rodent in question turned out to be a chipmunk; more agreeable than a rat, there are few creatures more pleasing to observe than a little munky going about its business.

A motorised procession of visitors to the car park had taught the chipmunk to forage in close proximity to the area, as a potential meal might be shared by a visitor. Strictly speaking it is wrong to feed wild animals in national parks: certainly feeding bears will encourage them to hang out where there are people and this can be a death sentence for a bear, or even a visitor; but chipmunks usually get the better of the situation, although eating food that doesn’t come naturally may put an animal’s health at risk, because humans so often provide ridiculously inappropriate food.

A motorised procession of visitors to the car park had taught the chipmunk to forage in close proximity to the area, as a potential meal might be shared by a visitor. Strictly speaking it is wrong to feed wild animals in national parks: certainly feeding bears will encourage them to hang out where there are people and this can be a death sentence for a bear, or even a visitor; but chipmunks usually get the better of the situation, although eating food that doesn’t come naturally may put an animal’s health at risk, because humans so often provide ridiculously inappropriate food.

Fortunately, we don’t need to feed the chipmunk to get pictures; other visitors had already done that, and we’d interrupted the chipmunk’s searching. As we eat our lunch I photograph the little creature, and encouragingly she is finding food growing naturally. This seems rather unusual, as I’m accustomed to seeing wild animals eating anything but natural food in and around car parks — usually it is something sugary and sticky attached to a plastic wrapper.

I started to imagine a scenario relating specifically to car parks and their surrounding ecology. In could see in my mind mature fruit trees and other non-native plants growing about the place, having established themselves from the scatterings of various seeds and fruits tossed from car windows and missed by local animals. I imagined a new species of chipmunk evolving under these circumstances, one that could only exist around old car parks, entirely reliant on introduced fruit trees for their meals; but it was a silly idea — we are far better at destroying useful habitats than creating new ones… our speciality is to reduce diversity and cause species loss.

We move on to a car park higher in the mountains, where the air is much cleaner than we are used to, and walk across the screes of an alpine desert. Our route takes the usual form of a circuit, but I have difficulty in making progress because there is so much to photograph in an environment that is entirely new to me. The walk is not strenuous, but it takes time to get back to the car park, where things are getting interesting.

I noticed at once a golden-mantled ground squirrel that seemed a little bigger than the ones I was used to seeing. It wasn’t the newly evolved form I’d imagined earlier so reliant on car parks, but there was no doubt that these squirrels were accustomed to getting free meals from visitors. Further investigation revealed that the ‘new’ rodent was a cascade golden-mantled ground squirrel Callospermophilus saturatus, a species close to becoming endangered with a very restricted range.

To see ground squirrels amongst the smaller chipmunks was a surprise and although I’ve photographed a good many during my 40 years travelling around North America, today the challenge would be to get both in the same picture to demonstrate the size difference, but try as I might I couldn’t manage to do so despite an hour of trying.

But everything would change for the better when a girl drove into the car park and began attracting attention… in particular from the rodents I was trying to photograph. Very quickly they left me and went over to the young woman who had arrived carrying appropriate food — a mixture of seeds and unsalted nuts, and very soon she was feeding both species next to her car causing the little creatures to show up in numbers.

From an animal welfare perspective she knew exactly what was safe for ground squirrels to eat. I asked if I might take photographs and she had no objection, but I won’t reveal her identity because there are rules about feeding wild animals in national parks, even when doing so provides a rare and vulnerable species with a little extra food to help them through what, up in the mountain, is a long harsh winter: the ground squirrel will be up and about feeding through summer for little more than four months of the year.

Usually, people who scatter seed indiscriminately (mostly for song birds), will do more harm than good because any surplus food will attract vermin; frequently rats will show up to the party and there is a direct link between increasing rat populations and the damage they will do the following spring raiding bird nest in increased numbers. This makes over-supplying food in a previous season counterproductive; but if the time between feeding and nest raiding is over a long period, it becomes difficult for people to link the two: feeding wild animals is certainly a mistake unless it is done sparingly.

The young woman provided only what the animals could carry away, no more and no less, and although some purists might disagree; her actions probably were not too much of a problem; and certainly she provided the added bonus for me of pictures. If I’m honest about 20% of my career has been spent photographing wildlife that is hanging around close to car parks. In such places animals become accustomed to the presence of people and pick up an opportunistic meal, although in most cases a not especially healthy one.

Trails can be equally productive at attracting wildlife, especially when they cut through a forest. Along the borders of woodland, some species become easier to find than in the forest, perhaps visiting a tree or shrub that is flowering or fruiting in the more open conditions and such places are ideal for wildlife photography. When I have time I wait and allow wildlife to come to me, but more often than not the best results are achieved by a stake out. Sometimes, the open trail as you walk along it is enough in itself. I’m usually on the look out for reptiles basking in the undergrowth in sunny areas on either side of a path, and such opportunities can also work out well for seeing small mammals.

A few years ago Jen and I were walking a trail high in the Rocky mountains, when we noticed a ground squirrel that seemed very accustomed to people showing no signs of fear as we passed by. So we hung around to see how close the animal would come to us. After a while the chipmunk came right up to our feet with the intention I believe of gaining what he or she had obtained from other walkers – a free meal, but we had no suitable food to offer; in any case the chipmunk was clearly very well fed and did not need a supplementary feed, although this didn’t stop the little creature from making a thorough seach of the camera bag put down beside the trail.

A few years ago Jen and I were walking a trail high in the Rocky mountains, when we noticed a ground squirrel that seemed very accustomed to people showing no signs of fear as we passed by. So we hung around to see how close the animal would come to us. After a while the chipmunk came right up to our feet with the intention I believe of gaining what he or she had obtained from other walkers – a free meal, but we had no suitable food to offer; in any case the chipmunk was clearly very well fed and did not need a supplementary feed, although this didn’t stop the little creature from making a thorough seach of the camera bag put down beside the trail.

After we had been watching the squirrel for quite some time, Jen crouched down to get a closer picture with her small point and shoot camera and the squirrel which had still not been offered any food took its chance to do a search of her clothing, and pretty soon was up in the hood of her coat, doing a fair bit of damage to the lining, just in case she was hiding contraband there of an edible nature; then perhaps frustrated by finding nothing to eat started and intensive investigation of her hair which involved pulling at it. I of course asked Jen to just put up with the situation, while I took a series of photographs.

After we had been watching the squirrel for quite some time, Jen crouched down to get a closer picture with her small point and shoot camera and the squirrel which had still not been offered any food took its chance to do a search of her clothing, and pretty soon was up in the hood of her coat, doing a fair bit of damage to the lining, just in case she was hiding contraband there of an edible nature; then perhaps frustrated by finding nothing to eat started and intensive investigation of her hair which involved pulling at it. I of course asked Jen to just put up with the situation, while I took a series of photographs.

We were with the little munky for perhaps 20 minutes and then thought it best to move on. The squirrel followed us for a while, until she decided we were a lost cause and started off back along the trail to where we had first encountered it, to no doubt wait for the next muggable passer by. The scenery we walked through that day was extraordinary, but in retrospect it was the memory of a small rodent engaging with us in the hope of finding an easy meal that we remember… How pleased we were to not have engaged in similar fashion with a bear.

High in the mountains ground squirrels have only a short period of time to forage for food before going into hibernation. As chipmunks are small they would find it difficult to get through seven or eight months in full hibernation, so they store food in their burrows during the summer months and regularly wake up to feed during the winter. The larger ground squirrels however build up fat reserves through the summer and hibernate right through without waking to feed, surviving entirely on accumulated body fat.

I won’t pretend that the identification of ground squirrels is that difficult once you get the hang of it: chipmunks, ground squirrels and prairie dogs are all part of the same group and known are known as marmots. The Columbian ground squirrel that we are familiar with is one of the mid-sized squirrels and has a similar distribution to golden-mantled ground squirrels, with a restricted range that runs down from the Rocky Mountain region of Alberta and British Columbia into the USA.

I have photographed ground squirrels in several States of North America, but the last time I spent a lot of time filming them for television was way back in the mid-1980s, in and around Albuquerque where they were common on flat expanses of open prairie isolated by surrounding development; but in recent years things have been breaking bad for the ones I filmed in Albuquerque; as their habitat has been steadily over-run by urban development.

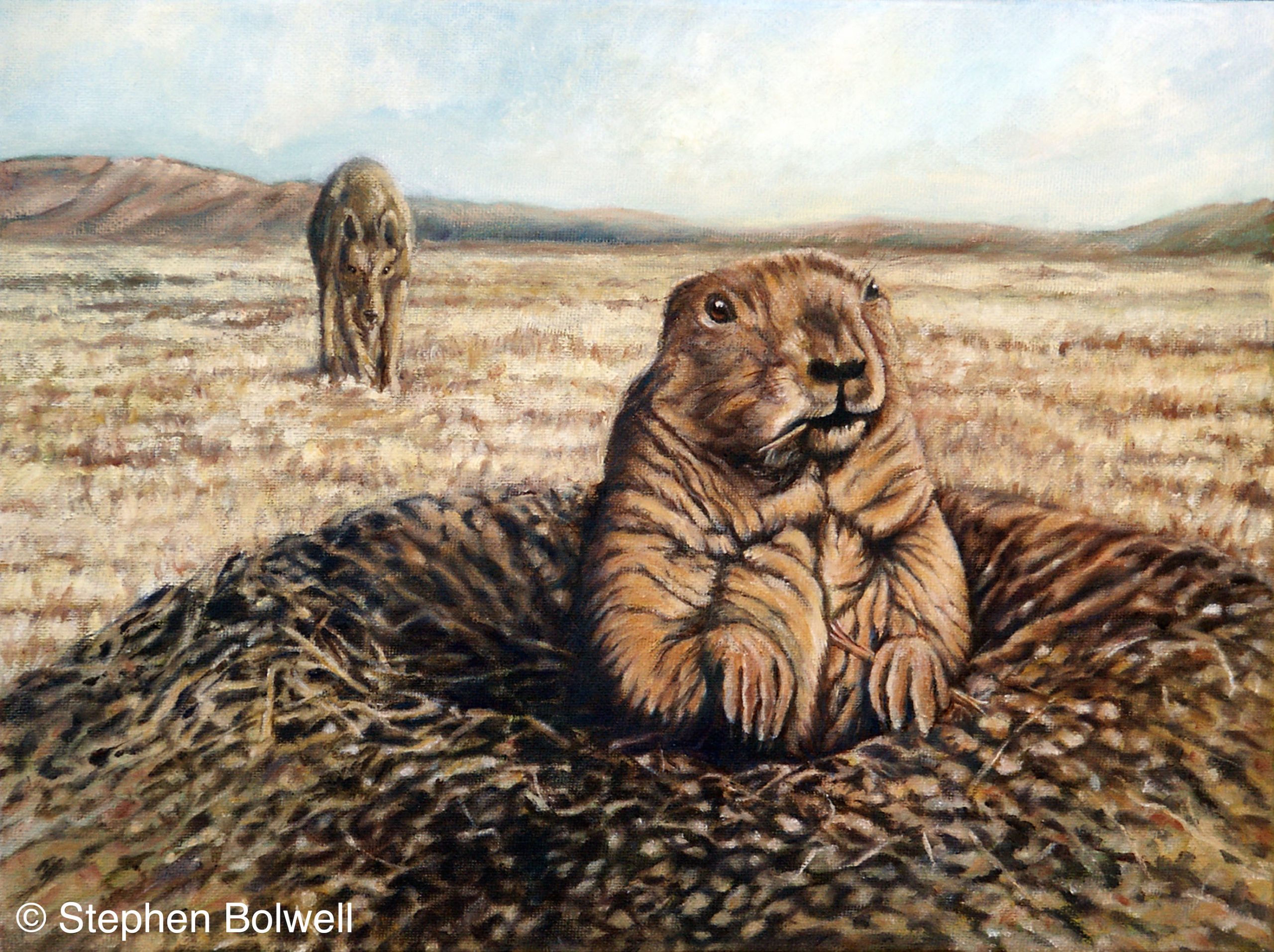

On open plains these animals spend a lot of time standing on their hind legs watching out for predators which makes it difficult to approach them to get a picture, because out on a prairie they usually dive away into their communal burrows when they see you coming and living communally they will kick up racket and warn others of your approach.

Many people call almost anything that lives underground a gopher — there is even a gopher snake, but a true gopher is from family Geomyidae and not closely related to the ground squirrels mentioned here. They have prominent incisor teeth, bare tails and rarely come to the surface… which is probably why I’ve never managed to photograph one.

It isn’t worth getting too worked up about terminology: when it comes to members of the ground squirrel family Sciuridae: they spend only part of their lives underground as opposed to true gophers which live most of their lives below ground. The climbing squirrels most commonly seen in and around trees are not easily misidentified. You don’t usually see ground squirrel’s bouncing around high above in trees, so they do not need big tails for balancing, these would in any case prove a nuisance underground and are consequently much reduced in size.

The smallest members of the family are the chipmunks, the medium sized ones are usually termed ground squirrels and the larger family members such as the prairie dogs are commonly described as Marmots. Filming the bigger ones, especially groundhogs often becomes ‘just another one of those days’. The process can be bleak because you have to repeat the same day over and over again until you film a sequence right before you can give up and go home… and when you’ve been doing that repeatedly, you sometimes feel like killing yourself.

Prairie dogs (of the Genus Cynomys) are herbivorous burrowing rodents and were once widespread across the plains of North America, However their numbers have been much reduced in the last hundred years or so because they are considered to be a pest by many and have been much persecuted, despite being a native species very much tied to the landscape. In semi-desert areas their burrows allow rainfall to get more directly to the water table before it can evaporate; and their nibbling ways stimulates the growth of several plant species making the squirrels an essential part of the prairie ecosystem. They do compete with grazing livestock, but this is a recent phenomenon, and unlike cattle and horses, have a very long association with the prairies of North America.

My favourite family member will always be the chipmunk which has a widespread distribution across the continent. This little creature seems to be always busy, always inquisitive, and with such endearing behaviours it is not difficult to see why chipmunks are amongst the most well liked members of the rodent family.