Everybody who meets a lion in the wild has a story to tell and I am no exception – all the pictures of wild animals were taken on the Serengeti (apart from the Cape buffalo photographed at Ngorongoro Crater).

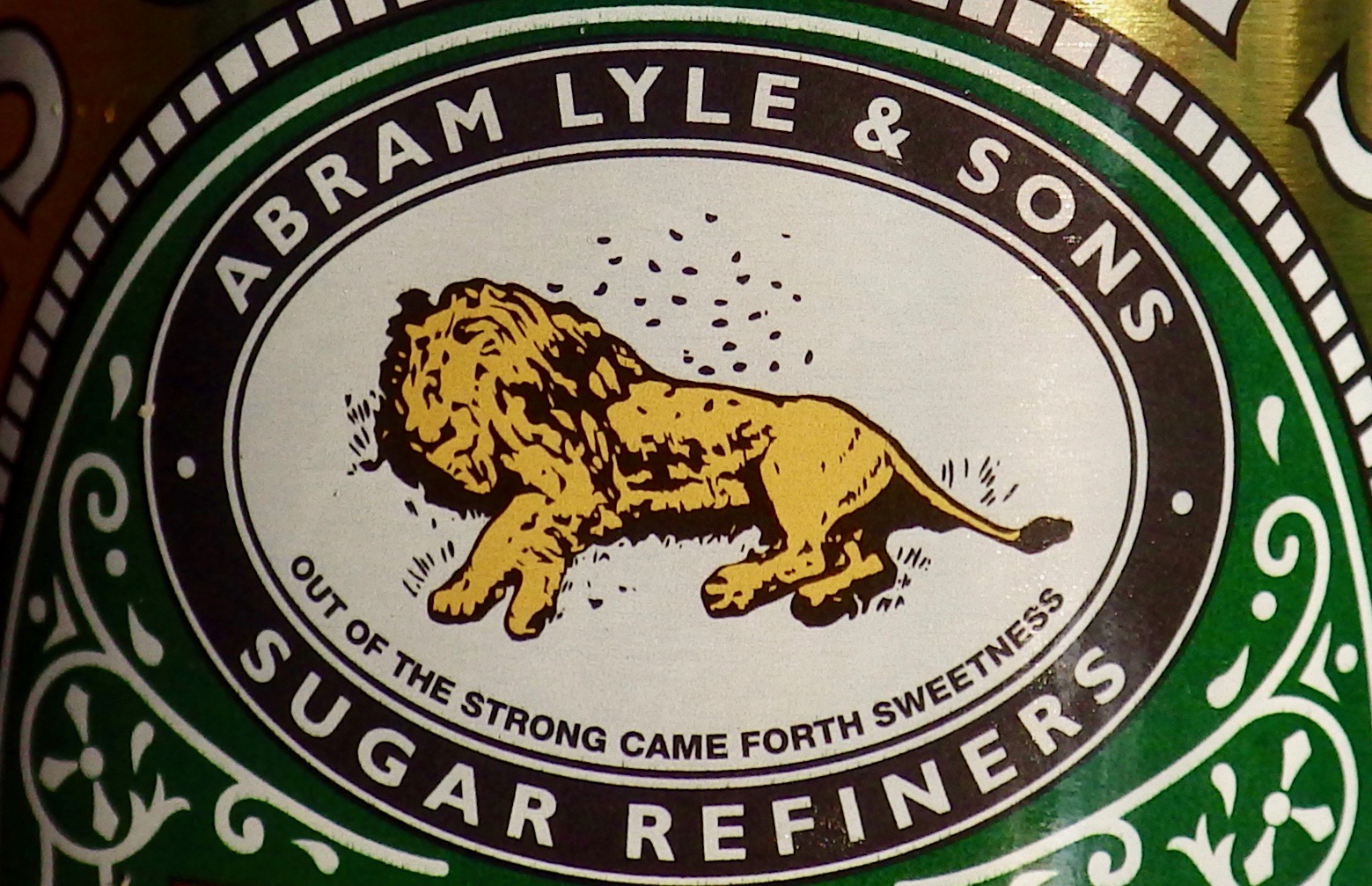

When I was a child my first sighting of a lion was on a Tate & Lyle golden treacle tin, the one that showed up on the table whenever there was steamed pudding. On the front was a picture of a male lion surrounded by a swarm of bees: this, I was told showed the lion to be the king of the jungle because nothing could bother him; but the truth is rather more shocking: the lion is dead and the bees have come from his body – this image relates to a biblical story involving Samson killing a lion – on his return to the body he noticed, as it says on the tin, that ‘Out of the strong came forth sweetness’. I had not an inkling of this symbolism when I was a child, but it didn’t matter, there are few animals, dead or alive, more impressive than a lion, especially when you are small.

When I was a child my first sighting of a lion was on a Tate & Lyle golden treacle tin, the one that showed up on the table whenever there was steamed pudding. On the front was a picture of a male lion surrounded by a swarm of bees: this, I was told showed the lion to be the king of the jungle because nothing could bother him; but the truth is rather more shocking: the lion is dead and the bees have come from his body – this image relates to a biblical story involving Samson killing a lion – on his return to the body he noticed, as it says on the tin, that ‘Out of the strong came forth sweetness’. I had not an inkling of this symbolism when I was a child, but it didn’t matter, there are few animals, dead or alive, more impressive than a lion, especially when you are small.

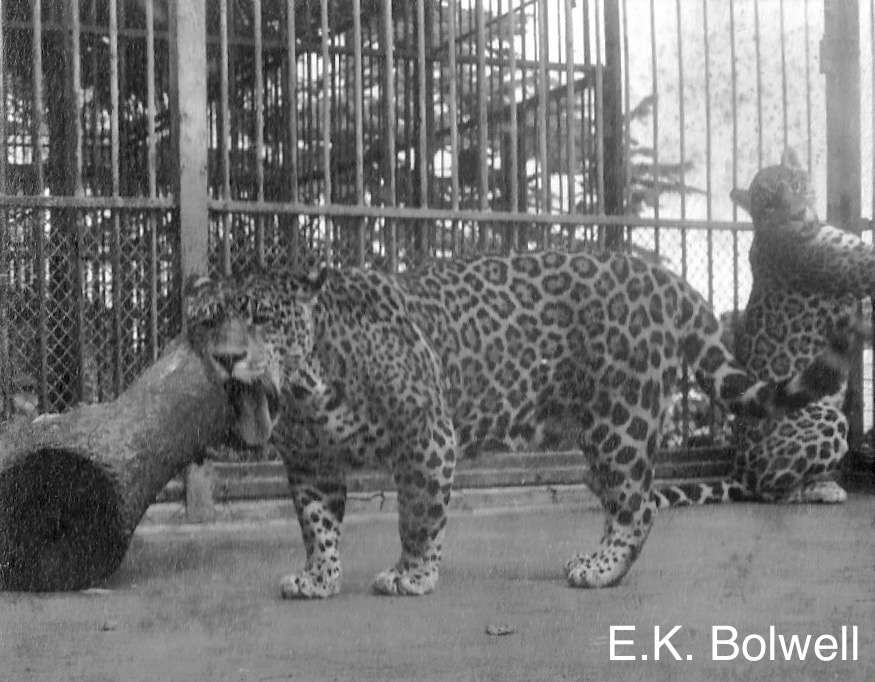

Not long after I was taken to see caged lions at the zoo, back then this was not an edifying experience as big cats were invariably kept in small enclosures surrounded by bars. The pacing creatures were dead behind the eyes, and what was left of their minds seemed damaged.

Lions featured only occasionally during my childhood and apart from a few soft toys all were caged. When safari parks began to open, living conditions improved, but most captive cats didn’t lead natural lives; my impression was that many were bored and just waiting patiently for their keepers to make a mistake.

Lions featured only occasionally during my childhood and apart from a few soft toys all were caged. When safari parks began to open, living conditions improved, but most captive cats didn’t lead natural lives; my impression was that many were bored and just waiting patiently for their keepers to make a mistake.

When I grew up and began photographing wildlife, I experienced big cats both in zoos and in their natural habitats; and without doubt some of the captive animals were more dangerous than their counterparts in the wild, although for me, it was a long time before I saw them wandering free.

By my mid-twenties the closest I managed to get to a lion was when working at a television station. I stole away from my office to join the circus. A ring had been set up in one of the studios and as the lions came into their arena they passed along a flimsy wire passage and I stood at a small gap between the two as they rushed by; it was an exhilarating moment, but hardly natural, and it would be another four years before I got close to big cats in the wild after receiving the telephone call of a lifetime.

By my mid-twenties the closest I managed to get to a lion was when working at a television station. I stole away from my office to join the circus. A ring had been set up in one of the studios and as the lions came into their arena they passed along a flimsy wire passage and I stood at a small gap between the two as they rushed by; it was an exhilarating moment, but hardly natural, and it would be another four years before I got close to big cats in the wild after receiving the telephone call of a lifetime.

When the call came early in 1979 I was working in a high-rise building close by London’s South Bank, writing film scripts for the Government’s Central Office of Information – a job that I wasn’t very good at. I remember thinking we were all hurtling towards 1984 and my position was similar to Winston Smith’s in George Orwell’s dystopian novel of the same name, although in truth my role in government propaganda was fairly harmless, nevertheless I was struggling with it. This was my chance to get valuable production experience, but all I wanted to do was get away on some expedition or other, and with my limited finances that was just wishful thinking. The desire to walk out and never return was extreme and the unexpected incoming call was about to make that possible. It came from BBC Natural History Unit producer Barry Paine who had seen some of my film work and was now inviting me to join him and a small crew on a safari to Tanzania. Barry was making two wildlife documentaries on the Serengeti and was offering me the chance of a lifetime. So, I finished up my work, said goodbye to my colleagues and walked out: my lifestyle had taken a turn for the better and pretty soon I would be travelling to remote destinations to film the natural world.

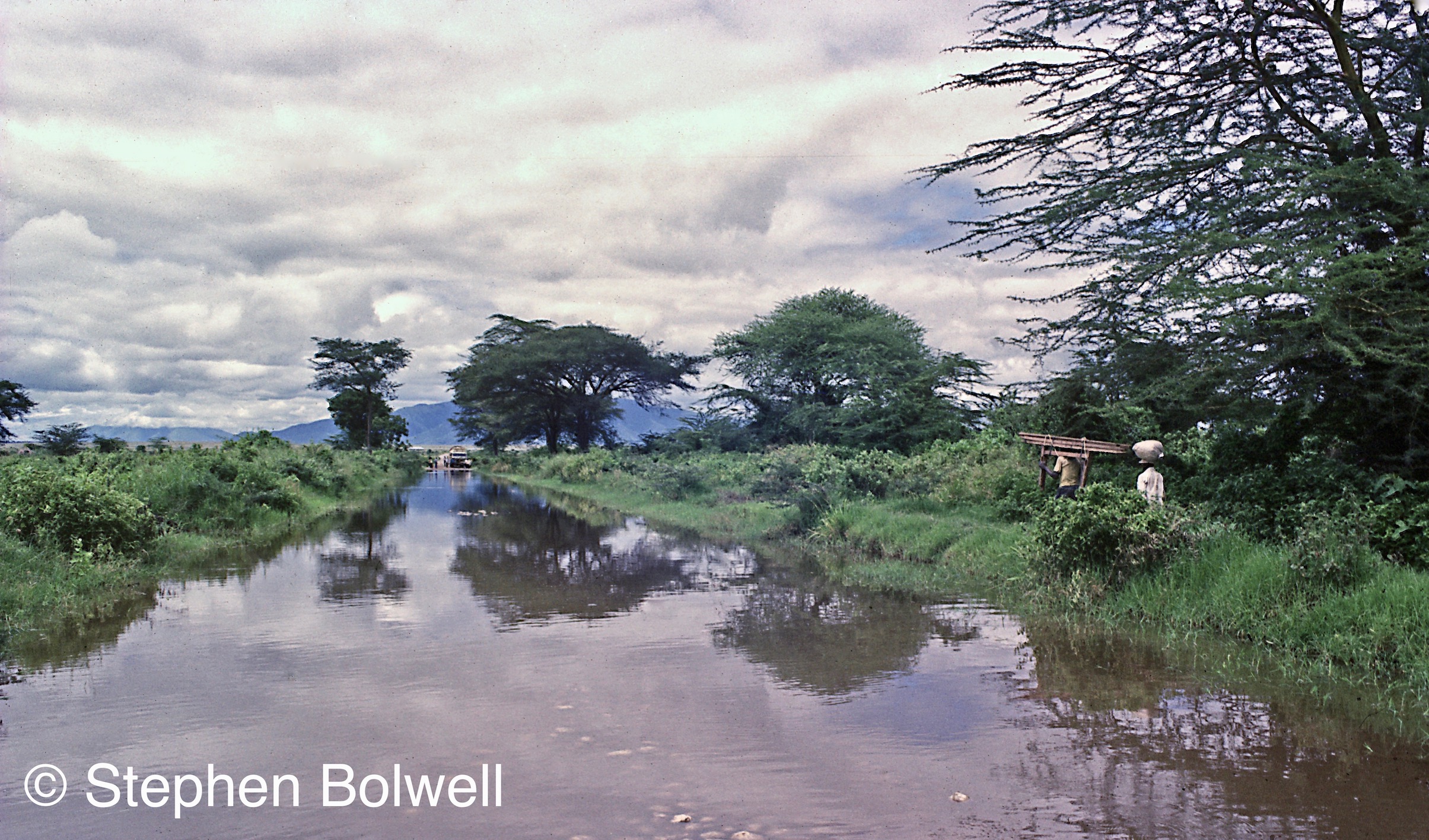

In 1979 the Serengeti wasn’t the easiest place to get to from Britain, it was an expensive destination and once you’d made it to Tanzania there were still difficult roads to negotiate, especially during the rainy seasons which come twice a year, but it hardly ever rains for long. One day there might be a downpour, then things clear very quickly and this can make travelling a matter of pot luck.

To the north, Kenya’s National Parks were an easier option for tourists – essentially this is a matter of travelling times – nobody wants to spend half their holiday just getting too and from their destination, but places worth seeing often take longer to get to… It’s part of what makes them special.

We would visit the Serengeti twice over the course of a year to cover both a dry and a wet season, with a total safari time measuring in months rather than weeks – the trips were well beyond anything I could afford, especially to move the equipment – back then the flight excess baggage bills alone would have covered a substantial down payment on a very nice house, but the experience of a special place is always worthwhile, especially when somebody else is paying.

We travelled from London Heathrow to Kilimanjaro Airport and then drove to the old hunting capital of Arusha, then a two day journey to Seronera Wildlife Lodge in the middle of the Serengeti: the length of the journey being entirely dependent on the state of the roads.

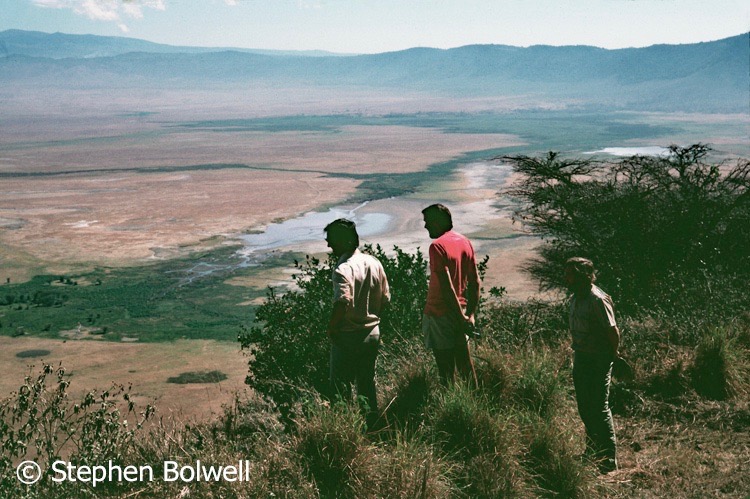

Ngorongoro

We had an overnight at a Lodge on the rim of Ngorongoro Crater and I instantly got myself into trouble, stepping out of the vehicle and walking too close to a Cape buffalo to take a picture. Old bulls pushed out of the herd on the crater floor often come up to the rim to feed and invariably they are bad tempered.

One minute the old bull was eating grass, the next, his head was up and he was moving towards me, but his intent didn’t seem convincing. A group of locals close by went suddenly quiet, I could see they were interested in my unfortunate situation as I was a good deal nearer the buffalo than any building or vehicle. There didn’t seem much else to do but stand my ground and whether this tempered the creature’s mood I will never know; I thought it more likely that this bulky animal couldn’t be bothered to relocate to where I was standing. I didn’t maintain eye contact, looking away to avoid challenging him… maybe he’d think I wasn’t even there! The standing around seemed to go on for an eternity, but outside of my world, it was probably no more than thirty seconds. Tired of looking at me, the bull snorted, waved his head a little and then went back to eating grass. The light was now almost too poor for an exposure, but I took a couple of pictures anyway and then slowly backed away. Two of the boys who had been watching, whistled through their teeth and were now cheerfully smiling at my good fortune. It was unusual for me to do something without calculating the risk, but the experience proved a positive one – a reminder that you must never take Africa for granted: despite its many wonders, a disrespected Africa can ruin your day.

Our small team of four went off to our rooms and within an hour were ready to walk the short distance to the dinning area – this a large thatched building busy with pictures taken by photographers who had been working the area for many years.

Before we started out, Robin had heard a knocking at his door and thinking this the arrival of another member of our party he had opened it, only to find an old bull standing directly in-front of him, the animal’s horns spanning too widely to enter the room. ‘So, what did you do?’ I later asked him. ‘I just shut the door’, he replied. Shortly after this incident we were gathered together and escorted to the dining area by a very small man carrying a very big spear.

My introduction to East Africa had been a little absurd, but there wasn’t a hint of any of that in the breath taking views. In spite of an increasing human population, there are large tracts of wilderness that remain intact. The National Parks however face many problems – local people have for generations driven their stock animals across borders into conservation areas, and poachers are regular visitors. Sadly, the same old problems that have existed for generations are still around and they have been increasing in recent years.

Barry had decided to give a new operator a chance at organising our safari, and in doing so he probably achieved a really good deal: our safari was by no means plush, but the staff were at least reliable and initially things ran very smoothly, but it soon became clear that servicing our remote locations was going to be a problem: at one point we ran out of food and had to eat rotten meat that tasted of ammonia – for safety reasons we ate it almost burnt to a cinder. In the end, all that was available was a local maize porridge, which I would happily fill up on at any time of the day until even that ran out: the situation was less than ideal and we all came away a little thinner than we started out.

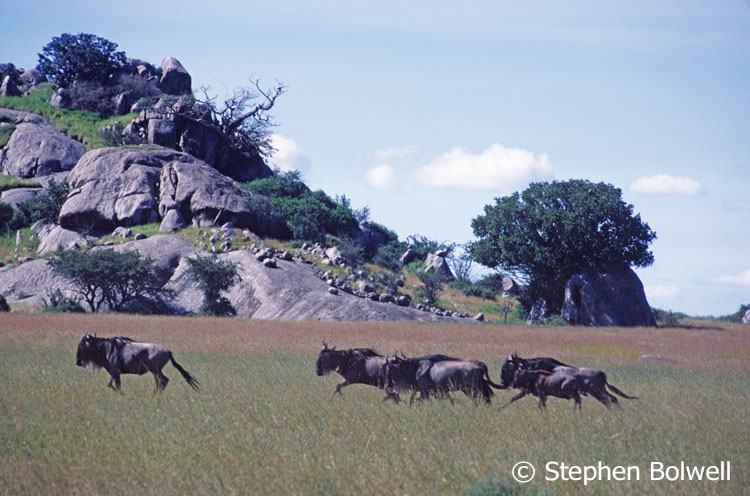

The experience was worth it though, because back then the Serengeti was mostly unbroken grassland; more recently some areas have become criss-crossed with tyre tracks, but I remember the Savannah as pristine; at no time did we see another vehicle or person who wasn’t a member of our team (apart from a couple of scientists who were working on ecology projects). The Serengeti seemed, back then, very isolated from the outside world: it was the first place I had visited so completely free from sound pollution that I was conscious of my heart beating.

Our Safari organiser was a South African – I’ll call him Donald (although that wasn’t his real name). Around Donald unusual things would happened: he had for example a fairly cavalier attitude to the potential dangers of the Serengeti. On several occasions when his vehicle broke down, he would walk miles to get to the camp; and on one occasion arrived so close to nightfall, he was followed in by a gaggle of lions.

One of our camps was set at the remote Simba Kopje: the name in itself should have been a give away, but the lions that hung out there were disturbed when the camp was being set up and they moved out, but after a week or so began to return to this their favoured rocky outcrop.

Almost any sound is enough to wake me from sleep and hyenas would occasionally do so when padding past my tent at night. These carnivores are more closely related to cats than dogs, but classified in a family of their own. We always referred to them as paddies, perhaps because of their facial similarity to Paddington Bear, or maybe it was for no better reason than they would pad about the place – I never thought to ask.

Early on, we heard there had been a recent attack on a young German who was sharing a tent with a friend. He was keen on astronomy and had been sleeping with his head outside of the tent in order to gaze up at the stars as he dropped off to sleep. One morning his friend, who slept entirely under canvas, unzipped the entrance to discover that the star gazers head had gone. Whether it is possible for a hyena to remove a human head without disturbing its associated body is open to question, but this was not an encouraging story to hear at a time when hyenas were coming close by your tent on a nightly basis.

On a night to remember

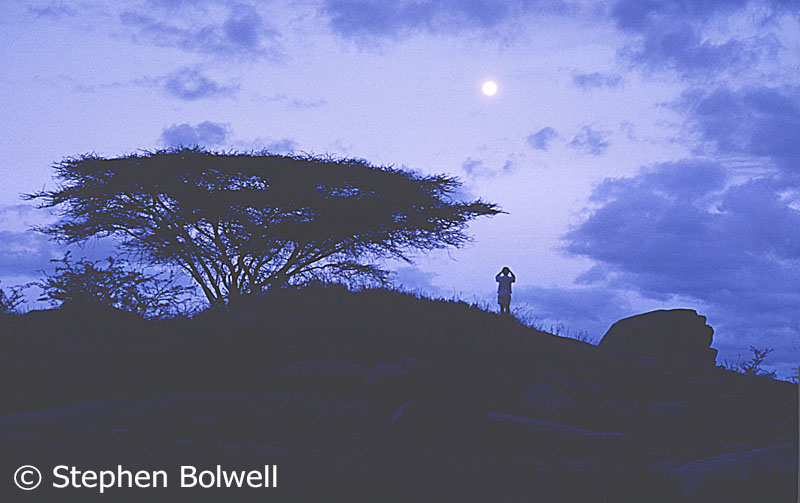

I heard a hyena pad along close by the end of my tent, its proximity was unnerving, but there was worse to come. I was laying awake thinking the hyena might return when quite suddenly there was a considerable noise and several things began to go over around the camp… in particular around a tent just one down from mine. Then I heard a voice, ‘Shoo, shoo …’ it was saying, and I undid my tent flaps to see what was going on: it was the time of a full moon which made observations easier, and to my surprise Donald, who was a slight wiry man, was running about after a lioness. I soon noticed that there were several more, he’d be following one and then suddenly turning he’d run after another – it was madness. So far the cats were just trying to avoid Donland’s attentions, but how much longer they’d put up with him was anybodies guess. Everybody else in the camp appeared to have gone mute, and because Donald was now quite close to my tent I felt obliged to try and talk him back into his – it was the least I could do as I certainly had no intention of going out to help him. I began speaking in an odd, but to my mind, encouraging whisper. ‘Get back in your tent Donald – you know you have to stay in your tent’. This one way conversation continued for some time, but to no avail; Donald took absolutely no notice and continued with his hectic shooing. The light was hyper-luminous, the moon casting long black shadows across the landscape as Donald continued to participate in this strange hypnotic ‘ballet of the big cats’. Before me were all the features of a surrealist dream, the only problem – I was wide awake. It seemed extraordinary, to be thousands of miles from my usual life experiences, in an East African wilderness trying to encourage a small man not to dance with lions in the moonlight.

The next day we found Douglas in the back of his Land Rover – he told us that on the previous night he had been lying on his camp bed when several young lionesses had started playing around his tent – I remember the relief that it was his tent and not mine. Donald remained calm until his tent started to lurch about, but the final straw was a front paw tearing through canvas close by his head, which quite understandably caused him to lose his cool and burst out into the moonlight and run about like a madman.

It’s one thing to sit and watch large wild animals pass 20 metres from an open ended dining tent before darkness falls, but quite another to have your tent invaded by lions at night. This situation helped us decide to move away from Simba Kopje for a while. We did however return and on our second trip we also camped again beside Simba Kopje (not the outcrop of the same name said to look like the one in Disney’s animated film ‘The Lion King’). There were always lions moving about at night moving through the various kopjes, but we never had a second break in.

It’s one thing to sit and watch large wild animals pass 20 metres from an open ended dining tent before darkness falls, but quite another to have your tent invaded by lions at night. This situation helped us decide to move away from Simba Kopje for a while. We did however return and on our second trip we also camped again beside Simba Kopje (not the outcrop of the same name said to look like the one in Disney’s animated film ‘The Lion King’). There were always lions moving about at night moving through the various kopjes, but we never had a second break in.

It was not uncommon for us to lie on our beds in the dark listening out for three single males that were wandering our area; we would be assessing whether they were coming in our direction or moving away. From a distance their low bellowing contact calls could be heard carrying for miles across the open plain; and there were often several minutes between vocalisations, but never was there a time when these contact calls didn’t sound close – and when they were, it was almost as terrifying as having a lion in your tent. Our cook was philosophical about the situation – telling me in all seriousness, that a bellowing lion always sounds close, but there was no need to worry until you could smell his terrible breath.

It was not uncommon for us to lie on our beds in the dark listening out for three single males that were wandering our area; we would be assessing whether they were coming in our direction or moving away. From a distance their low bellowing contact calls could be heard carrying for miles across the open plain; and there were often several minutes between vocalisations, but never was there a time when these contact calls didn’t sound close – and when they were, it was almost as terrifying as having a lion in your tent. Our cook was philosophical about the situation – telling me in all seriousness, that a bellowing lion always sounds close, but there was no need to worry until you could smell his terrible breath.

The one thing it was unwise to do too frequently on the Serengeti was to walk about by yourself, but it was often necessary for me to do so. The crew would drop me off at a location and then drive off for a couple of hours to film something else.

Usually I would wander alone, but sometimes our guide Isiaka would accompany me; he carried an old Lee-Enfield rifle to protect us – I think from poachers rather than big animals. We knew that most poachers were well armed and we didn’t want to come across them, but as we rarely went out at night when they were most likely to be active, there were never any problems.

Working kopjes on foot has its dangers – but it was the only way to get good shots of insects, spiders, reptiles and rodents; which usually require a short or macro lens rather than the long lenses used to film larger animals from a vehicle. It was particularly foolhardy to spend too much time laying down without a lookout and this may be one of the reasons why smaller creatures are such frequently overlooked subjects here.

On one occasion I was set down beside a kopje with cameraman Hugh Maynard and he at once noticed a kestrel sitting on the branch of a tree growing up between two large rocks. Hugh suggested that I should walk up into the kopje where my presence might cause the bird to take off and improve his shot. As we weren’t regularly disturbing animals this didn’t seem unreasonable, but I needed to go deep into the rocky outcrop before I could get anywhere near the bird. All was going well until I came around a corner, and directly in my path was a male lion -and I had interrupted his lunch. That he already had food seemed the only positive thing about my situation, because I hadn’t thought to bring a plate to the party. On my arrival his head jerked suddenly up and there was no doubt that we were both surprised to see one another: his eyes widened and his eyebrows shot up. It is certainly anthropomorphic to say, but his gaze seemed quizzical, and I was hoping that he wasn’t weighing me up as a potential meal. For sometime we just looked at one another and I was careful not to break eye contact. I at least hadn’t startled him enough to make him come towards me, and I slowly began to move backwards taking care not to fall over as I felt about with each footstep. As soon as I was around a corner and out of sight, I turned and started to run as best I could in the rock strewn kopje until finally emerging onto the savannah. Hugh was standing about 20 metres from the base of the rocks. ‘Did you get your shot’, I asked, ‘Yes thanks’, he said, looking absent-mindedly through his viewfinder at something else. ‘Why were you running?’, he asked, ‘Because there’s a lion in the kopje’, I replied. There wasn’t much else to be said as he was clearly concentrating on scanning across the rocks with a long lens. Not long after Barry arrived with the Land Rover and we got in and drove around to the other side to see if there was anything else to film and when we were about halfway around, there on the rocks was the lion – he had moved now to a more exposed position. ‘F— Me! There’s a lion in the kopje’. said Hugh. ‘I already told you that’ I replied. ‘I thought you were joking’ he responded, ‘you weren’t running fast enough’.

On one occasion I was set down beside a kopje with cameraman Hugh Maynard and he at once noticed a kestrel sitting on the branch of a tree growing up between two large rocks. Hugh suggested that I should walk up into the kopje where my presence might cause the bird to take off and improve his shot. As we weren’t regularly disturbing animals this didn’t seem unreasonable, but I needed to go deep into the rocky outcrop before I could get anywhere near the bird. All was going well until I came around a corner, and directly in my path was a male lion -and I had interrupted his lunch. That he already had food seemed the only positive thing about my situation, because I hadn’t thought to bring a plate to the party. On my arrival his head jerked suddenly up and there was no doubt that we were both surprised to see one another: his eyes widened and his eyebrows shot up. It is certainly anthropomorphic to say, but his gaze seemed quizzical, and I was hoping that he wasn’t weighing me up as a potential meal. For sometime we just looked at one another and I was careful not to break eye contact. I at least hadn’t startled him enough to make him come towards me, and I slowly began to move backwards taking care not to fall over as I felt about with each footstep. As soon as I was around a corner and out of sight, I turned and started to run as best I could in the rock strewn kopje until finally emerging onto the savannah. Hugh was standing about 20 metres from the base of the rocks. ‘Did you get your shot’, I asked, ‘Yes thanks’, he said, looking absent-mindedly through his viewfinder at something else. ‘Why were you running?’, he asked, ‘Because there’s a lion in the kopje’, I replied. There wasn’t much else to be said as he was clearly concentrating on scanning across the rocks with a long lens. Not long after Barry arrived with the Land Rover and we got in and drove around to the other side to see if there was anything else to film and when we were about halfway around, there on the rocks was the lion – he had moved now to a more exposed position. ‘F— Me! There’s a lion in the kopje’. said Hugh. ‘I already told you that’ I replied. ‘I thought you were joking’ he responded, ‘you weren’t running fast enough’.

As things stand today the lion population on the Serengeti totals around 3,000 individuals, and combined with Ngorongoro holds the largest population of lions to be found anywhere in Africa.

In most places lion populations are seriously in decline, but on the Serengeti numbers are holding, despite many external pressures. National Geographic reported that there were 100,000 lions living in Africa during the 1960s, but only 32,000 were to be found at the end of 2012, the most likely reason for this loss was people pressure.

I won’t pretend that our involvement with a couple of natural history films back in 1979 was in any way consequential in conserving the Serengeti but it may have increased awareness, and certainly the experience provided me with a personal perspective on what was then a near pristine environment.

Every 30 years or so, we worry a little more about the changes each generation exerts on nature; with our observations usually recording a steady deterioration of ecosystems and the reduction of species within them. Worldwide this deterioration is rapidly accelerating, but once in a while somewhere special like the Serengeti holds out; nevertheless, there can be no certainties about the future and it is difficult to remain optimistic when the general trend continues to run so strongly against the natural world.

The films we were making: ‘Tree of Thorns’ and ‘Kopje: A Rock for All Seasons’ both written and narrated by Barry Paine. First transmissions on BBC 2 during 1980.