Each year I return to Southern England from British Columbia to visit my father, and during late March and early April catch up on what an English spring has to offer. This year was a bit different though, I arrived a little later than usual to attend my step-mother’s funeral and take time with my father after the sad event.

My father lives to the west of Southampton Water close to the New Forest; and having spent a lot of time filming and taking photographs in the area, I can seldom resist the opportunity to visit places familiar to me from childhood.

My wife’s mother lives to the east on Portsmouth Harbour and travelling back and forth between my father’s home and hers provided a good opportunity to witness this years unusual spring as a great many wild flowers were showing much earlier than expected.

On the 6th of April we drove from Fareham out through the Meon Valley and despite the dullness of the day the views were spectacular with hedgerows full of flowering Blackthorn Prunus spinosa, producing one of the most impressive Hampshire Blackthorn seasons I have ever witnessed.

I often see complicated descriptions on how to differentiate Blackthorn from Hawthorne Crataegus monogyna, by comparing flowers, but the two are easily identifiable once you are aware that Hawthorne comes into flower much later in the spring than does Blackthorn, and usually after the blackthorn flowers are over. The leaves of Blackthorn always appear after the flower have opened and appear ovate. Hawthorne leaves always show before their flowers and have characteristically indented margins (see picture), and so there is really no need to complicate the issue by making comparisons between flowers. Hawthorne is the only British plant to be named after a month; and the name of May tree is an indication as to when it was once most commonly seen in flower.

Blackthorn and Hawthorne are frequently used for hedge laying and we were able to see a good example at Manor Farm close by the River Hamble, this before too many leaves had emerged to hide the detail. A properly laid hedge such as this will provide a structure that is impossible for stock animals to push through.

A few days later I was back on the New Forest and quite disappointed by the amount of litter that had been scattered close by road sides, presumably thrown from passing cars. It is as if the British have no conception of how beautiful their countryside is and one of the reasons I was happy to leave the U.K. I became genuinely disturbed by the British attitude towards littering… People seem happy to live with it and I have no idea why.

There are of course a great many well intentioned individuals trying to clear up the rubbish, but as quickly as they pick the stuff up, others are chucking it down. I am pleased to say that on my most recent visit I noticed an improvement from last year, but there was still no shortage of trash along verges, particularly at cattle grids where vehicles inevitably slow, providing a better opportunity to hurl litter out without fear of it blowing back in.

N.b Rubbish is not of course entirely a U.K. problem. I note that Canadians produce more of it per head than almost any other country, but they dump far less of it along roadsides than do the British. Canada it seems has accidentally sent quite a lot of its waste off to the Philippines, which, at the time of writing, has been piling up in boats along the docks of Manila. According to the country’s president it is no longer welcome, and might soon be returned to where it came from.

More generally The New Forest appears little changed from the way it was when I was here last spring, its natural environments remain in decline, which is almost entirely due to overgrazing: I know I have written about this before and was hoping for an improvement, but on visiting a favourite area in the Beaulieu Marchwood area I discovered that nothing much had changed. If I was cynical I might think that somebody in authority was getting paid to claim overgrazing is not really a problem when so clearly it is; but of course I wouldn’t say that because such a thing would be unthinkable. What must be happening is that somebody with a greater understanding of New Forest management than I, is attempting something imperceptibly clever that I’ve failed to recognise. Whatever I might feel about the situation, there are many who don’t recognise the problem, in particular some of the commoners who receive subsidies to graze their stock on the Forest in what in recent years has become alarmingly high numbers.

I noticed along my favourite little slow flowing stream that common frogs had spawned. I saw three clumps where it usually shows up early in the year. I first started noticing frog spawn here in the early 1970s, but I didn’t see any sign that toads had spawned which I would have expected, and there were no grass snakes or adders in the area, although both were once common here. The only other wild animal I noticed was a male brimstone butterfly, Gonepteryx rhamni in flight, clearly on its way to somewhere far more interesting.

A broader stream once well protected from visiting stock by dense undergrowth is now a barren wasteland. I mentioned in a previous article watching a manic male adder moving rapidly through a scrubby bush here, stopping only briefly to take a look into a dartford warblers nest, but there is no chance of seeing anything like that now.

A broader stream once well protected from visiting stock by dense undergrowth is now a barren wasteland. I mentioned in a previous article watching a manic male adder moving rapidly through a scrubby bush here, stopping only briefly to take a look into a dartford warblers nest, but there is no chance of seeing anything like that now.

There was no sign of any ground nesting birds on the open heath… which is now almost completely lawn; and nearby oaks have been felled close by the stream. I have always understood the need for heathland management, but prefer it when habitats are as diverse as possible. I really don’t see any environmental improvements in a place I know quite well, but with only around 50 years making observations of this unique habitat I should perhaps ask myself – what do I know?

My father and mother-in-law have a combined age of about 190 but despite this they have interests that usually get me out and about. My father likes to lunch in old pubs and my mother-in-law particularly enjoys being driven through the English countryside. We combine the two and I stop to take pictures whenever I see something interesting, although I restrict my activities to just a short distance from the car.

This spring, I’ve eaten in a lot of old timber framed buildings, seen a lot of dogs lying on flagstone floors; and I’ve travelled through large tracts of Hampshire countryside witnessing a wide variety of wild-flowers – many in churchyards. I have very little interest in Gods of any kind, but find myself comfortable in places such as these: it is as if time has stood still for a very long time and you can glimpse the past, even if my view is an over simplified romantic version of the truth as moats of dust float in the coloured light of stained glass windows, and old churchyards tumble with a deluge of beautiful flowers.

It is inevitable that my father and I will visit St Nicholas Church at Brockenhurst, because. I spent the best part of a year making a B.B.C. natural history film there – and the other thing – my mother is buried in the graveyard.

This yard is particularly spectacular because an effort has been made to leave cutting the grass until the spring flowers are over. I was not surprised to see celandine, wood anemone and primroses at this time of year, but was too late for most of the daffodils, which was no great loss as I have a preference truly wild flowers.

Certainly things have not changed a great deal since I filmed here through 1983; back then the real guarantee that natural history would come first and the yard remain un-mowed until the spring flowers were over was the presence of Peter Reeves who was then looking after the yard. Peter was a knowledgable naturalist and sympathetic to all the wildlife that lived here.

This greater understanding of managing natural areas has been taken up by many churchyards with the tidy brigade held at bay until the bluebells have gone over; this more sympathetic environmental approach during spring is steadily catching on and preserving the beauty of a great many wildflower habitats including roadside verges.

This greater understanding of managing natural areas has been taken up by many churchyards with the tidy brigade held at bay until the bluebells have gone over; this more sympathetic environmental approach during spring is steadily catching on and preserving the beauty of a great many wildflower habitats including roadside verges.

I can’t feature every churchyard I visited, and so I’ve gone for a trio of Hampshire ‘All Saint’s’.

According to a lady putting flowers on a grave in the churchyard ‘All Saints’ has just two people in the congregation for a Sunday service: a reminder that low attendance is now a common problem for many country churches around Britain. If I lived close to a very old church that was as beautiful as this one, maybe even I’d attend if I thought it would help keep the place open. So many old churches are now being sold off to become domestic dwellings and in future we might not be able to visit them so freely. This will be a great loss.

We go in search for history in books and on the internet but so much is still contained in beautiful old buildings like ‘All Saints’. Inside the church the incumbents are listed from 1262 to the present day.

The climate is beginning to change

and there is little it seems that we as individuals can do about it, the problem requires a worldwide and concerted effort to halt the transformations that are now occurring. In this part of the world without so many frosty mornings in early spring wild flowers have been coming into flower much earlier than they once did. Some animal species such as amphibians have behavioural queues for activities such as spawning that are often set by day length rather than temperature – this is the reason some amphibian species may be seen gathering beneath ice in preparation for spawning even when it is still very cold. The opening of spring flowers on the other hand is in part controlled by temperature and in northern temperate regions spring flowers have been opening earlier year by year in line with the warmer conditions. During my April stay in southern England, wood anemone, celandines and wood violet were doing nicely and by the third week of the month bluebells were in flower with their arching racemes beginning to stand upright.

The problem with this eventuality is that nectar food sources concentrated as they are now, earlier in the spring, may mean less availability for insects later in the season with some pollinating insects experiencing a restricted choice: many insects are programmed to visit flowers at a certain time and pollinators might find their usual food source either past its best or no longer available. There will of course be a degree of adaptation to changing circumstances but this more condensed flowering period is a novelty that is increasingly becoming the norm.

My mother-in-law during our drives through the Meon Valley and along the Hamble River was delighted to see so many early flowers, but she won’t have to rely on flowering plants for her lunch through May when the many we are presently seeing have gone over.

On one of our days out we were driving out of Fareham, this a place where my father had spent most of his childhood , and it wasn’t long before we were passing a cemetery and my father said, “The last time I was here was in the 1930s at a relatives funeral”. I at once pulled the car over. “Do you remember where the burial was?” I asked. “I think so”. he replied. and so I drove back and we started our search, but it was fruitless; if there had been a gravestone to commemorate the event, it had long since gone.

Wickham was coincidentally also our next destination, but a much better end point than the Wickham Road Cemetary’s version of a next and more final destination. We were soon travelling to a far more agreeable place – the tea rooms in the Hampshire village of Wickham which was not so very far away, and who cares that we’d only recently managed to get through a pub lunch; certainly not my father who has never been known to refuse anything that looks like a bun or an ice cream. A jam and cream filled scone would not to sit long on any plate within an easy reaching distance.

When our children were small my wife and I spent endless afternoons in search of a perfect cream tea, travelling through Hampshire, Dorset and the Isle of Wight… So, we’d been here before as a family. Our most favoured tearooms usually involved a garden where we would mostly be at war with local wasps, but on this cool spring day we preferred to eat indoors, although inside or out, a cream tea in Wickham has so far never been a disappointment to me.

The second ‘All Saints’.

Once fuelled up we continued to drive on through the local area. Our final final destination would be East Meon where I have in the past also worked on film projects at All Saint’s Church.

I’ve photographed sheep grazing in this yard on various occasions – by selective grazing they maintain the churchyards meadowland habitat. I have also filmed jackdaws nesting in one of the tower’s upper round windows where walking out along a beam was scary enough, but when that beam turned out to be an unattached plank which began to swing down as I moved along it, I suddenly became a cartoon character scrambling back from whence I’ had come to avoid a potentially more permanent stay down in the yard.

My stay in England then was for me a pleasant trade off. Most days I’d visit a churchyard and most days eat with my father in a local pub

Completing the ‘All Saints Trio:

For a while I’d be thinking about Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s grave at All Saints, Minstead, which is yet another beautiful old New Forest church and as it is not very far from my father’s home we decided to make an early evening visit and then go on to the pub.

Sir Arthur’s body was originally buried in the garden of his nearby family home – it is claimed upright, in line with his rather unusual beliefs. He was a spiritualist and when his old home was sold in 1955 his body was re-interred at ‘All Saints’ Minstead: this was not entirely a popular decisions as his beliefs were even more unusual than the Christian ones in death he appeared to be involuntarily joining. His body was sited far enough away from the church so as not to offend Christian sensibility; but we can’t be sure what Sir Arthur thought about the move; as far as we know he has not been in contact with the living to express his opinion. There is no doubt however that these beautiful surroundings are a fitting place for the man who created the world’s most famous fictional detective.

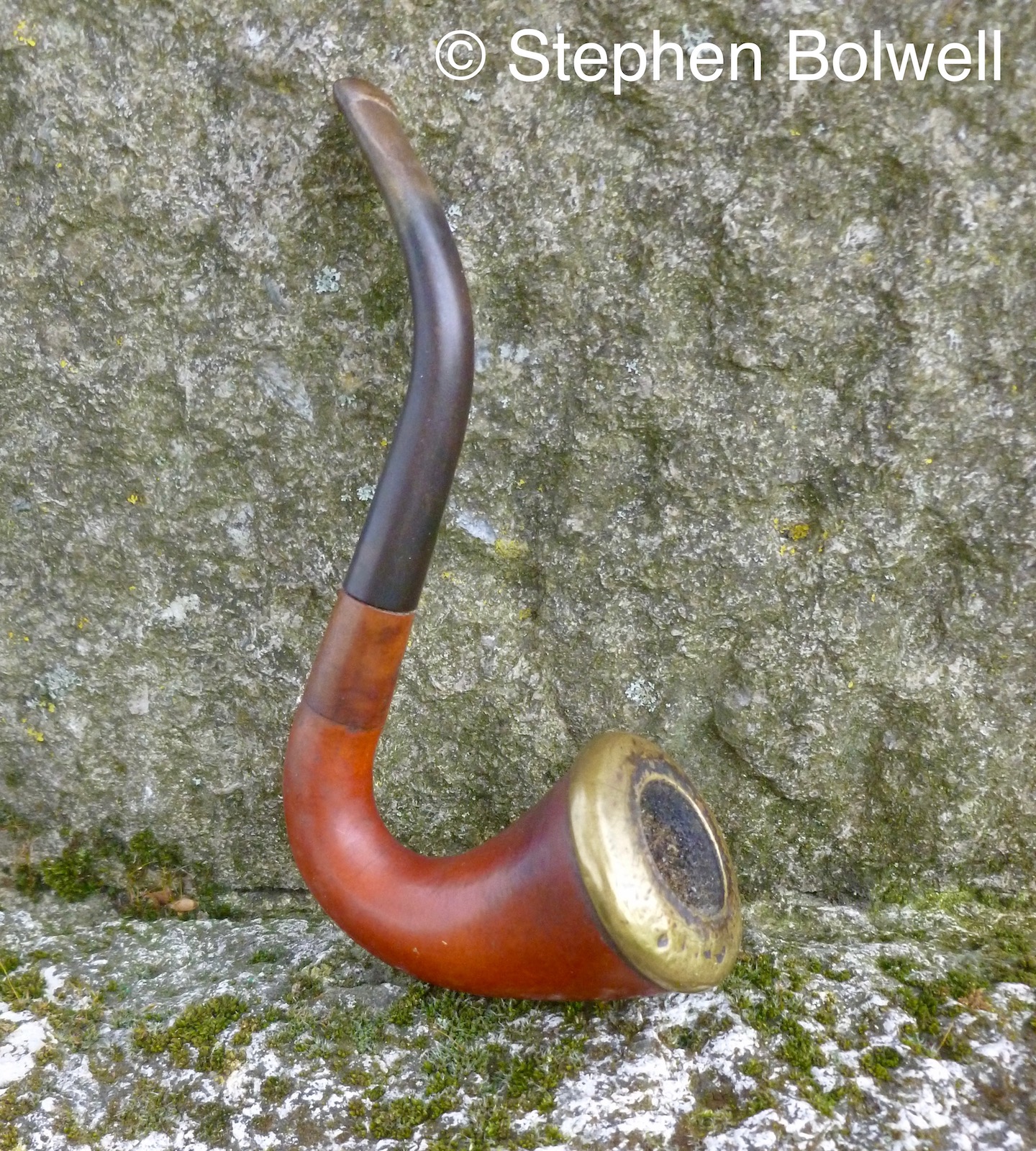

During my childhood it did not escape my notice that my father would occasionally smoke a Sherlock Holmes pipe; and far more recently I noticed that people were leaving pipes on Conan Doyle’s grave, which to my mind were the wrong sort of pipes; and so it was I went in search of my father’s, which I considered to be the most authentic – ‘the one true pipe’. After a bit of searching I found it in the top of my father’s wardrobe and brought it with us to be photographed at the grave, much to the amusement of my father; which was far and away the best reason for doing it, because keeping him cheerful was the priority.

Nothing is quite as it seems though: according to Conan Doyle, Holmes smoked several different types of pipe including a long stemmed cherrywood, a clay and a briar, but the ‘one true pipe’ as far as I was concerned was the curved one I’d seen in film versions of the Sherlock Holmes detective stories. With just a little research I soon discovered that a pipe with a curved stem makes it easier for an actor to speak with when held in the mouth – it is a question of balance – and it seems this form does not come directly from the original stories. It was suddenly clear that I had preconceived ideas concerning ‘the one true pipe’ and was wrong. There is a lesson here for us all. Nevertheless, I can’t stop thinking that ‘the one true pipe’ is the most photogenic of all the possibilities… surely that’s worth considering, at least as a reason for not being entirely wrong…

In the grand scheme of things I wasn’t that concerned about the fictional use of a pipe; my main reason for being in the churchyard was, as usual, dictated by an interest in natural history. I have always been fascinated by lichens growing on gravestones and those in ‘All Saints’ churchyard are quite spectacular.

Providing a tombstone is cut from soft limestone or sandstone rather than a hard polished granite, it will in Britain’s climate provide ideal conditions for lichen growth, but this can be a slow process. Lichens exist by mutualism, they are formed by a stable symbiotic relationship between algae and fungi which produces an organism that is very much different from its component parts.

Living immobile on a rock through the varied extremes of the seasons is a clever trick if you can pull it off; and I will admit that for many years I thought that the birds I saw landing on stones in churchyards were providing nutrients in their droppings that would aid growth, but as lichens do not have roots and rely almost entirely upon photosynthesis for their nutrition I should probably reconsider what I have supposed without the benefit of evidence: sometimes it’s hard to let go of preconceived ideas, whether they be a doctrinal belief, authenticating pipes in fiction, or how a lichen gains its nutrition. I know for a fact that in the last case, proof will come from careful observation and science will probably have all the answers; but it is the one subject out of all those mentioned that will interest most the least.

Our minds do not usually favour truths over a good story and so if I am going to feature lichens there is a better chance of interesting readers if I happen to mention Sherlock Holmes’ pipe.

With regard to lichens benefiting from the presence of bird droppings: I have just found a scientific paper that shows that bird droppings do increase the growth of some lichen species and slows the growth of others.

To be honest, I probably didn’t need to travel a quarter of the way around the world and stand in an English churchyard to discover that what I think I know, isn’t really what I know at all; and if this doesn’t quite work for me, maybe I could ditch science altogether and go with a more general approach by looking at the many alternative facts, that given half a chance, will suddenly pop into my mind.

Beautiful pictures and comments from the New Forest. I’ve been privileged to visit Brockenhurst in two intervals, traveling during my youth. Where can we find your film / video about the forest?

Thanks Bruce, I made quite a few N.F. films when working for the BBC. but during the 1990s made two which were sold on VHS, and the second one was also out on C.D.. I haven’t been selling them for so long I am not sure where you might find one, but there were a lot produced. The first was called ‘The New Forest – A History and Natural History’ narrated by Fred Dinenage. The second was a straight natural history film called, ‘An English Forest’. They haven’t dated too much as nature doesn’t change a lot – there is just less of it now. The original films were generated on 16mm film and might be transferred to H.D., but neither of these were presented in H.D., and if you do find them, don’t expect the picture quality you will see on your T.V. today. With all good wishes, S.B.