Science and Its Relationship to Climate Change:

On the 40th Anniversary of the first World Climate Change Conference (Geneva 1979), a statement was published in the Journal of Bioscience, signed by 11,000 scientists advocating a curb on population growth, a halt to forest destruction, a change of attitudes to meat production, and a reduction in reliance on fossil fuels: all with the intention of combating the climate emergency.

By 2016 studies indicated that 90-100% of scientists believed that climate change was real, and if climate deniers wanted confirmation of their beliefs it would be best to consult amongst the doubting 10% and avoid those better informed where the census was up around 97%.

Those with a vested interest in climate change, and politicians wishing to maintain support amongst deniers have regularly consulted with those who have the least expertise in an effort to elicit doubt.

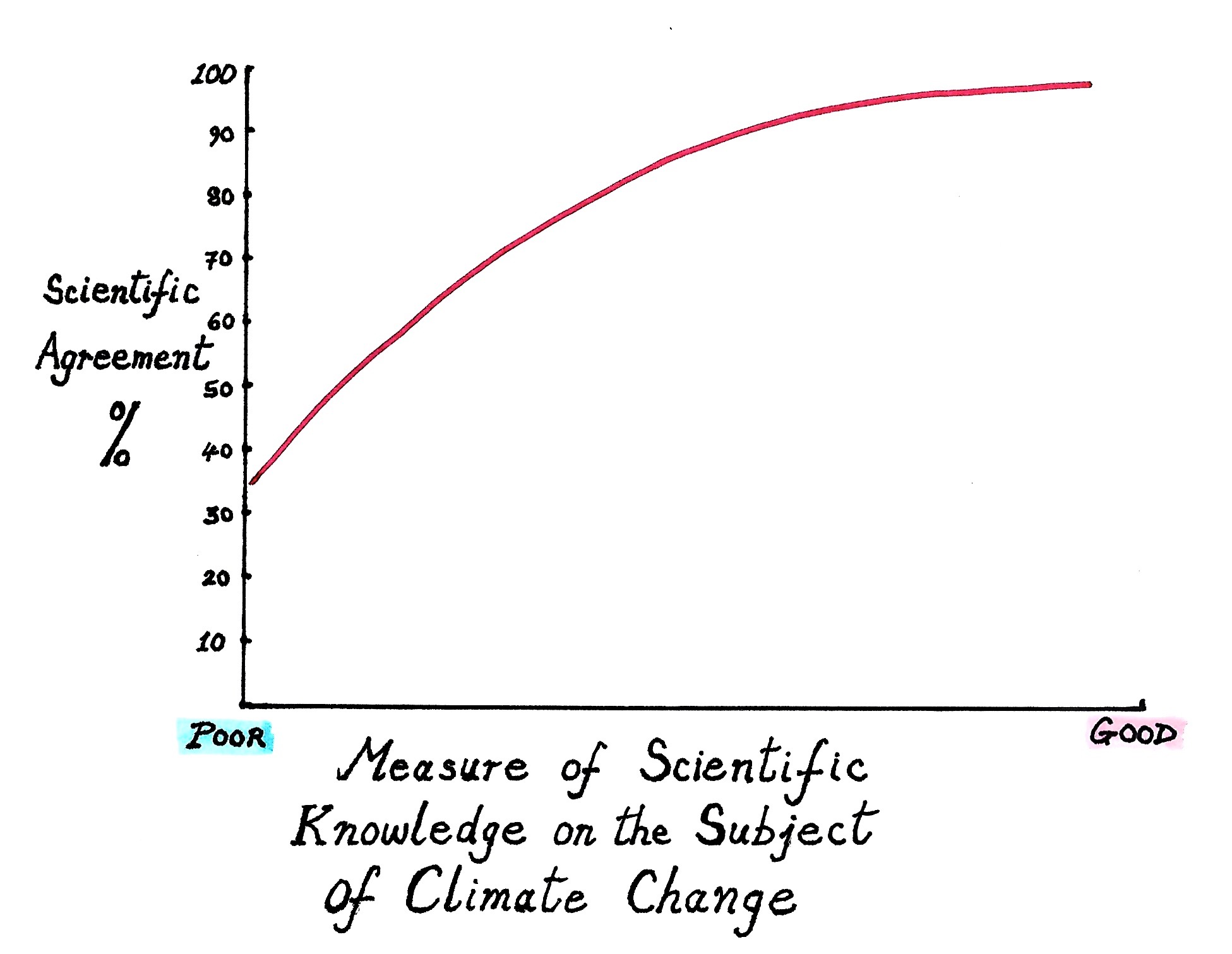

By 2016 various papers had been published on ‘Scientific Consensus’ in relation to ‘Knowledge’

and an interpretation of some of them is shown in the graph below. At a glance, the base line looks dodgy: running from POOR to GOOD isn’t a precise way to measure anything, and must be considered unreliable.

Nevertheless, the top end of the graph is supported by other research projects that indicate a high degree of consensus amongst the most knowledgeable – nothing seems wrong here; but at the bottom end where scientific knowledge is poor, precision of measurement becomes more difficult because it all depends on how knowledge is being measured and who is being asked.

With this in mind the graph could start almost anywhere, but despite this there is clear evidence that the closer scientists work to climate change, the more likely they are to agree that it is happening: something in the science must be influencing their conclusions, whilst the less well informed demonstrate a greater bias, or they just don’t know enough to draw reliable conclusions. The abstract Consensus on Consensus. 2016. John Cook et al. looks at the relationship more closely.

We can’t be expected to follow every line of scientific of research, but are always better informed by science than matters of opinion. For those who choose not to accept the scientific consensus it is a matter of cherry picking the evidence to support personal beliefs; visiting the internet is a good way to do this, because what we see there will be ruled by digital algorithms that use our previous search histories to select what we see next.

If we want to confirm our beliefs in really stupid things, the World Wide Web maximizes our chances of doing so; it can even put us in contact with like minded people… Despite this, the internet is not the enemy of rational thinking, but an unfortunate quirk of the way the system operates causes it to search for information in a way that scientists don’t, which reinforces bias. Science works hard to avoid such a thing; prioritising facts over opinions it accumulates knowledge and opens up possibilities. The internet can be equally informative, but used uncritically it quickly reinforces our preconceptions, narrows our thinking and sometimes leads us away from the truth – not that a mistaken or surrealist thought is always a bad thing, it’s just isn’t the best way to deal with global warming – we need to keep it real.

If we want to confirm our beliefs in really stupid things, the World Wide Web maximizes our chances of doing so; it can even put us in contact with like minded people… Despite this, the internet is not the enemy of rational thinking, but an unfortunate quirk of the way the system operates causes it to search for information in a way that scientists don’t, which reinforces bias. Science works hard to avoid such a thing; prioritising facts over opinions it accumulates knowledge and opens up possibilities. The internet can be equally informative, but used uncritically it quickly reinforces our preconceptions, narrows our thinking and sometimes leads us away from the truth – not that a mistaken or surrealist thought is always a bad thing, it’s just isn’t the best way to deal with global warming – we need to keep it real.

If we fail to confirm our beliefs amongst the scientific community, and can’t find what we need on the internet (which seems unlikely), there are any number of fake scientists and conspiracy theorists who can supply us with alternative views on evidence based information; but those who want to stay closer to the truth, it is best to consult studies that are recognised by others accredited in the field. Over the last four years the percentage of scientists who believe that anthropogenic climate change is happening, has been rising and is now at around 99%.

Quite possibly, we are living through one of the most challenging centuries humanity will face – twenty years in, the likelihood that 11,000 scientists are wrong about the climate emergency is unlikely.

What we know:

- Carbon release into the atmosphere is increasing and human activity is the cause. Agriculture, forestry and industry are factors and the burning of fossil fuels is especially consequential and causing the Planet to warm.

2. The process is being monitored by scientists, and efforts are being made to convince politicians to act responsibly, limiting Carbon release to moderate the warming effect.

3. This must happen soon, because there are potential turning points beyond which it will be impossible to recover.

4. What needs to be done is clearly understood, but progress in combating climate change has been slow and there is cause for concern.

5. Some of us seem complacently smug about making small personal changes without fully appreciating the magnitude of the situation – small changes in lifestyle will not be enough.

If governments are to combat climate change, they must take action soon:

many world leaders and their governments have so far avoided coming into line with the Paris Climate Change Agreement – the first worldwide legally binding accord on climate; adopted at ‘The Paris Climate Conference’ (COP21) in December 2015 it set a framework to reduce Carbon emissions by limiting global temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with a target increase of not more than 1.5°C by the end of the Century.

The most recent Conference of Parties (COP25) recently took place in Madrid, and there was a pervasive sense of frustration amongst delegates because many governments fell short of prescribed temperature rise targets, and in some cases delayed meeting them altogether.

Unfortunately, there has been a mismatch between what scientists know and how politicians behave in light of the facts. Climate scientists tend to be pessimistic about the current trend in rising global temperatures whilst politicians are more optimistic – in part because, when they take time to consult scientific research (which is by no means a given), they reach conclusions in a way that scientists don’t, cherrypicking the evidence that best suits their policies. The reality is, their goals are very different.

A Cross Section of Scientists and Politicians Stand Together.

Science is a rigorous process with the fine details being continuously refined; it never stands still and those working in different disciplines may not have enough expertise to make value judgements outside of their field. So, what chance do the rest of us have? Well, not a lot, but if the science under consideration derives from a prestigious scientific journal such as ‘Science’ or ‘Nature’, we can be fairly confident of the veracity of the published work, everything will have been vigorously peer reviewed, and we should pay attention to the conclusions because science is not a matter of opinion to be countered by ‘alternative facts’. There is in any case usually no need to get sniffy about less prestigious publications, as most are peer reviewed journals and in consequence reliable, although it is wise to be discerning. ‘The Journal of Little Green Men’, probably doesn’t need to be on your reading list unless all your research is being done on social media.

The result of Britain’s December 2019 general election was interesting because Parties with strong environmental policies (such as the Green Party) did not make inroads into votes going to more traditional parties. This raises the question as to how the electorate can be persuaded to vote for politicians prioritizing environmental issues over other concerns, because If this can’t be done, the traditional parties will have to be pushed into do doing far more to combat climate change.

Motivating individuals to react proactively to the climate crisis has been difficult; a great many people will happily admit to the problem, but so far, few have been inclined to vote for change. Tell people that it is necessary to keep global temperature increase down to 1.5°C over a century and they show very little interest – probably because the information is presented with no sense of urgency and it doesn’t spur individuals on to demand action from their leaders. Recently, Brexit split Britain with clear opinions for and against and there was a clear understanding that this was an important issue; but compared to rapid species loss, declining natural environments and climate change, it might prove in the longterm to be far less consequential.

Britain has experienced some really warm summers during the last century. The summer of 1976 stands out in my mind in particular because I spent a good many days filming heathland and woodland fires. Going back through meteorological records there have been many hot summers, but nothing compares to the present. The last 9 years have, globally, been the hottest on record.

Ian Bateman of Exeter University has authored a new study published in Nature – Food, and spoken about the effect of the warming climate on agriculture in Britain. He says that a standard rise of 2°C of global temperature over an average lifetime might initially benefit agriculture, as past warmer years have usually benefited food production; but if conditions should become too dry, it would be necessary to pipe water to the eastern side of the country from the north and west – these regions of higher rainfall; the cost of doing this would most likely eliminate any profit from the increased production; and if temperatures kept rising the benefits would be short term.

The scenario could be even more worrying if global warming proved to be more extreme, say a 3°C rise in temperature resulting in a more rapid melting of the Arctic ice and Greenland ice sheets which might turn off the Gulf Stream bringing warm water up from the Caribbean to flow around Britain. The Gulf Stream presently provides a warmer temperate climate than Britain could reasonably expect from its northern geographical position. If the stream just flowed (as it might) from west to east across the Atlantic and never reached Britain the results would be catastrophic.

With the Gulf Stream off, Britain’s food production would be reduced by a third or worse. The Islands rely on food imports from other countries and if a reduction in food production is widespread, feeding Britain’s ever increasing population would in retrospect make Brexit seem trivial: unfortunately, it is sometimes difficult to visualise ahead of time which are ‘the most important’ of ‘the most important things’ to worry about.

There is however some good news: a change of emphasis has occurred in the way science and the media deal with environmental issues and climate change. In the past scientists never expected their many years of research to lead to the public interpreting the findings and acting appropriately, or expect politicians to act quickly on issues related by their work. The interpretation of science has always been the job of the media – with varying degrees of success – but with the present immediacy of environmental issues scientists have become more inclined to speak out, and the current mood of the media is to provide them a platform to do so.

Twenty years ago it was difficult to find scientists capable of engaging public interest; those that could, would often transition to the media where they were more likely to be listened to and the money was better; but things are changing – why would scientists allow their ideas to be re-jigged by media personalities if they are able to speak effectively for themselves?

Professor Andrew Shepherd from the University of Leeds recently spoke to great effect on the melting of Greenland’s ice sheets and potential changes in sea level; he explained the current scientific work concisely and without melodrama – in part because the current scientific work is so dramatically clear there is no need to overstate the case. The Planet has been heating for the last 30 or 40 years, and we have shown little concern for the consequences – and in the last ten years the Greenland ice sheets have begun to melt at a much faster rate than predicted.

I fly from Vancouver to London Heathrow in early spring to visit my father in Southern England. Airlines usually take the most direct route flying north east over the white wilderness of Canada; then over the Labrador Sea before reaching the extensive permafrost and ice sheets of Greenland – these northern landmasses keep you thinking the great white north will never end. But in the most literal sense, it seems they will, with things now changing more rapidly than expected.

I fly from Vancouver to London Heathrow in early spring to visit my father in Southern England. Airlines usually take the most direct route flying north east over the white wilderness of Canada; then over the Labrador Sea before reaching the extensive permafrost and ice sheets of Greenland – these northern landmasses keep you thinking the great white north will never end. But in the most literal sense, it seems they will, with things now changing more rapidly than expected.

The Arctic is melting faster than was the case 25 years ago when snowfall was countering ice sheet and glacier melts into the ocean. Since 1992 3.8 trillion tonnes of ice has disappeared from Greenland, with water flowing into the Ocean causing a rise in sea levels of 10.6 millimetres – this might not seem a lot, but for every centimetre rise, around 6 million people are put at risk and likely to experience at least one flooding event each year. Inevitably, without action, this can only get worse.

Greenland is losing ice 7 times faster than was the case in the 1990s and if the warming continues many millions of people will be exposed to coastal flooding by the end of the century. A current IPCC projection demonstrates that if the situation continues at the present rate the melt from Greenland could push sea levels to rise by 8 or 9 centimetres by the end of the century. If it were just 7 centimetres which is a conservative estimate, the results would still be devastating for coastal areas and low lying communities around the world.

The Annual Arctic Report Card 2019 shows the Arctic is melting at an alarming rate, and much faster than scientists had previously anticipated. Without immediate action melting permafrost could soon release 600 million tonnes of Carbon (C) and Methane (CH4) into the atmosphere.

None of this is speculation – monitoring ice sheets by comparing satellite images over time provides compelling evidence of the problem. Perhaps we should think about this in the same way we consider a close relative dying – there is never a convenient moment, but it has to be dealt with appropriately.

In the Antarctic scientists are now working on ‘The Doomsday Glacier’ which is falling into the sea at a rate of two miles a year. Thwaites Glacier sits on a vast basin of ice with a front that measures almost 100 miles across. At the point where the glacier approaches the sea the landmass forms a ridge that dips back under the base of the glacier and favours water flowing back landward; and this contact with water is hastening ice melt. It is startling to think that around 90% of the worlds fresh water is locked up in Antarctic ice with Thwaites Glacier presently containing half a meter of potential sea level rise. If the Western Arctic ice sheet should also melt which is possible, the loss will be equivalent to an astonishing 3 metres sea level rise .

If emissions of global warming gases were cut significantly the impact on reducing rising sea levels would be significant, but if temperatures continue to go up things will only get worse. There is still time to react, but as yet not enough is being done to hit global Carbon emission targets. In the end, the necessary changes might be driven by concerns over the dire economic consequences of doing nothing, rather than any loss of life or unfavourable changes to natural environments. As odd as it might seem it might be business interests that push politicians towards better outcomes.

We are now close to reaching critical turning points which would lead to irreversible changes to the way global systems operate. Scientist might disagree on exactly when these changes will occur, and some changes might not occur all at once, they could perhaps move by degrees; and if we adapt our behaviours to changing conditions we might stave off imminent disaster; but abrupt switching points beyond which there are no returns remain frightening possibilities.

There have already been climate changes directly related to human behaviour and such events can no longer be ignored. Making predictions about almost anything has a degree of variability, and not knowing exactly when irreversible changes will occur, plays into the hands of those wishing to demonstrate that climate change isn’t really happening. Ironically, there is nothing worse than reaching a turning point, only to discover that ‘you’re not quite there yet’, although anything that buys time for leaders to react proactively must be a good thing, but with climate change happening more quickly that anticipated, there isn’ the luxury of too much time.

There have already been climate changes directly related to human behaviour and such events can no longer be ignored. Making predictions about almost anything has a degree of variability, and not knowing exactly when irreversible changes will occur, plays into the hands of those wishing to demonstrate that climate change isn’t really happening. Ironically, there is nothing worse than reaching a turning point, only to discover that ‘you’re not quite there yet’, although anything that buys time for leaders to react proactively must be a good thing, but with climate change happening more quickly that anticipated, there isn’ the luxury of too much time.

It is difficult to convince people that things will go wrong before they happen, and often a disaster must occur to precipitate a reaction. On occasions, big companies behave cynical: recognising a potential problem that might prove hazardous, they plough on without making changes, in the hope that profitability will exceed future insurance claims. However, when it comes to the climate emergency, refusing to act proactively is not a realistic option: if there are turning points beyond which we can no longer achieve stability we must act quickly; many children seem aware of the urgency – politicians… not so much.

With such huge profits being made from fossil fuels it is easy to understand why producers are reticent to give them up.

There has always been an unwillingness to factor in the millions of years of chemical and physical reactions that go into forming high energy fossil fuels, and the problems associated with the release of huge amounts of stored natural energy in such a short space of time has been largely ignored.

It seems we are best at solving immediate short term problems – our brain’s evolutionary course has left it inadequately wired to deal with uncomfortable situations that unfold over longer periods, and it might be necessary to start compensating for our ‘fallibility of thinking’. However, now that climate change is unfolding so rapidly, we might begin to see things more clearly. Run away ice melts in polar regions are just one of many signs of serious change and reinforce the view that 11,000 scientists are unlikely to be wrong about climate change. We must accept the evidence and push our politicians to act appropriately… and most important of all, they must do it soon.