Is the Coronavirus emergency a dry run for how climate change will be dealt with in the not too distant future? If that is the case there is cause for concern.

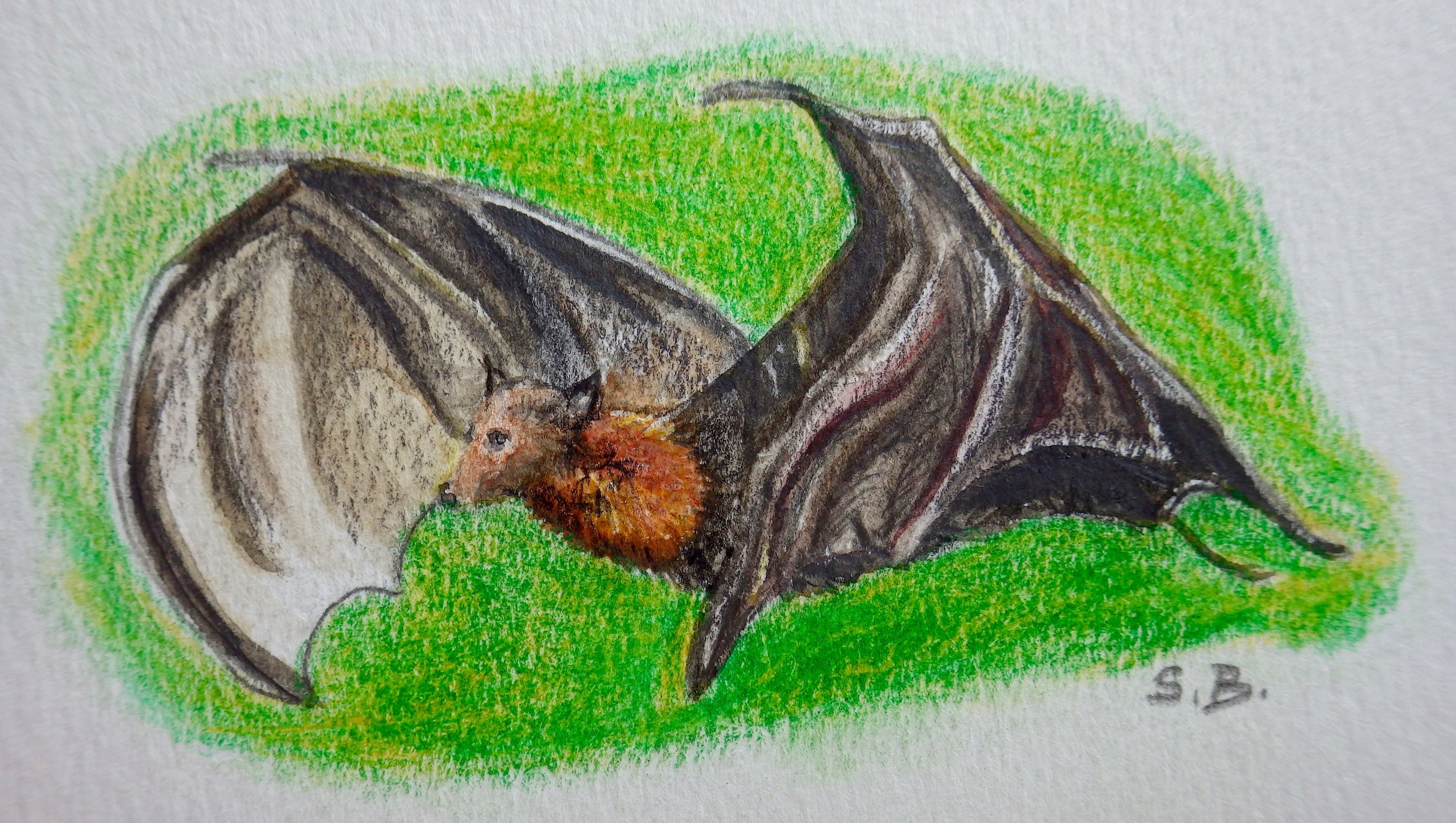

On December 31st 2019 China reported several cases of an unusual from of pneumonia in Wuhan, a port city in Hubei province. Some of those infected worked in a local fish market, which was quickly shut down. The virus responsible was a member of the coronavirus family, a new variation on a very basic plan: imperceptible to the naked eye, this tiny organism crossed over from a wild creature to a human being – it wasn’t the first time this has happened and it won’t be the last. The original host is still in question, but thought to have been a bat, although the virus may have passed through an intermediary, perhaps a pangolin, which is odd because pangolins are a critically endangered species.

The Chinese have an insatiable desire for pangolin scales, with the creature’s meat a delicacy. Years ago a Chinese friend joked that if it moved, the Chinese will eat it, which sounded racist even back in 1985, but I couldn’t help myself and said, ‘Just like the French.” We both laughed, but not as loudly as the Belgian standing next to us. We were beneath the shade of a big old tree in Central Africa, with there was nobody around to get offended on somebody else’s behalf. I was trying to buy the python my Chinese friend was fattening up in a sack under his house – he said it would make good soup, but I’m fond of snakes and was doing my best to keep the creature alive. The reptile had grown large and my friend had decided to present it to me just before I flew out on a light aircraft – with a pilot who was extremely concerned, but he needn’t have worried, the reptile escaped without my help. Had I taken the creature on board I might have claimed this the inspiration for ‘Snakes on a Plane’, but there was no chance of that now we’d escaped a potential disaster… It was quite the reverse from how things are today with the recently emerged coronavirus getting on a planes and proving itself infinitely more deadly than any reptile, travelling as it would in the respiratory systems of passengers, almost unnoticed – apart from a few raised temperatures and irritating coughs. This enterprising virus would get to almost any location that a human might decide to travel, and do so very quickly. Persistent and infectious this mutant coronavirus would make any snake related disaster imaginable seem like a minor inconvenience.

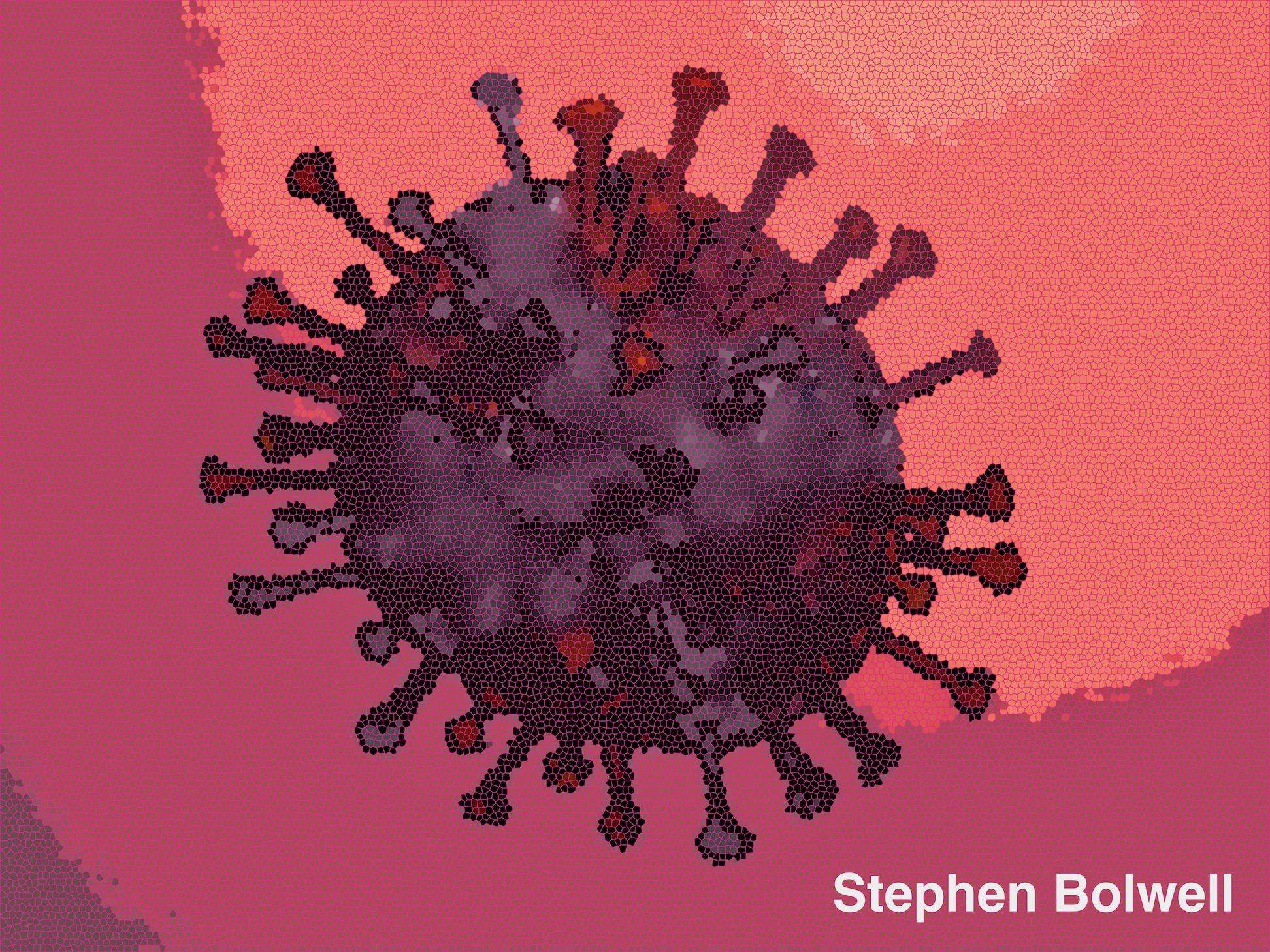

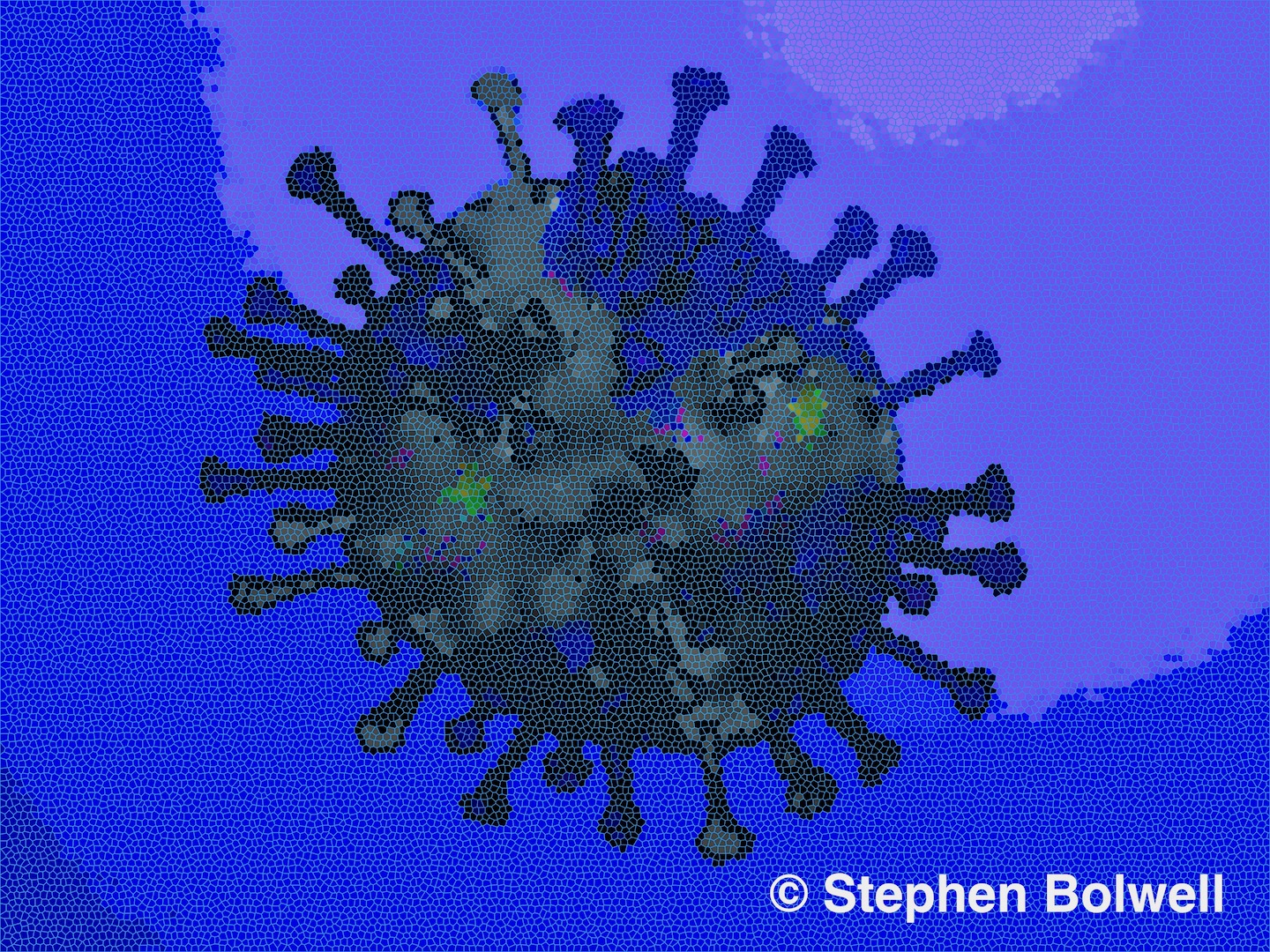

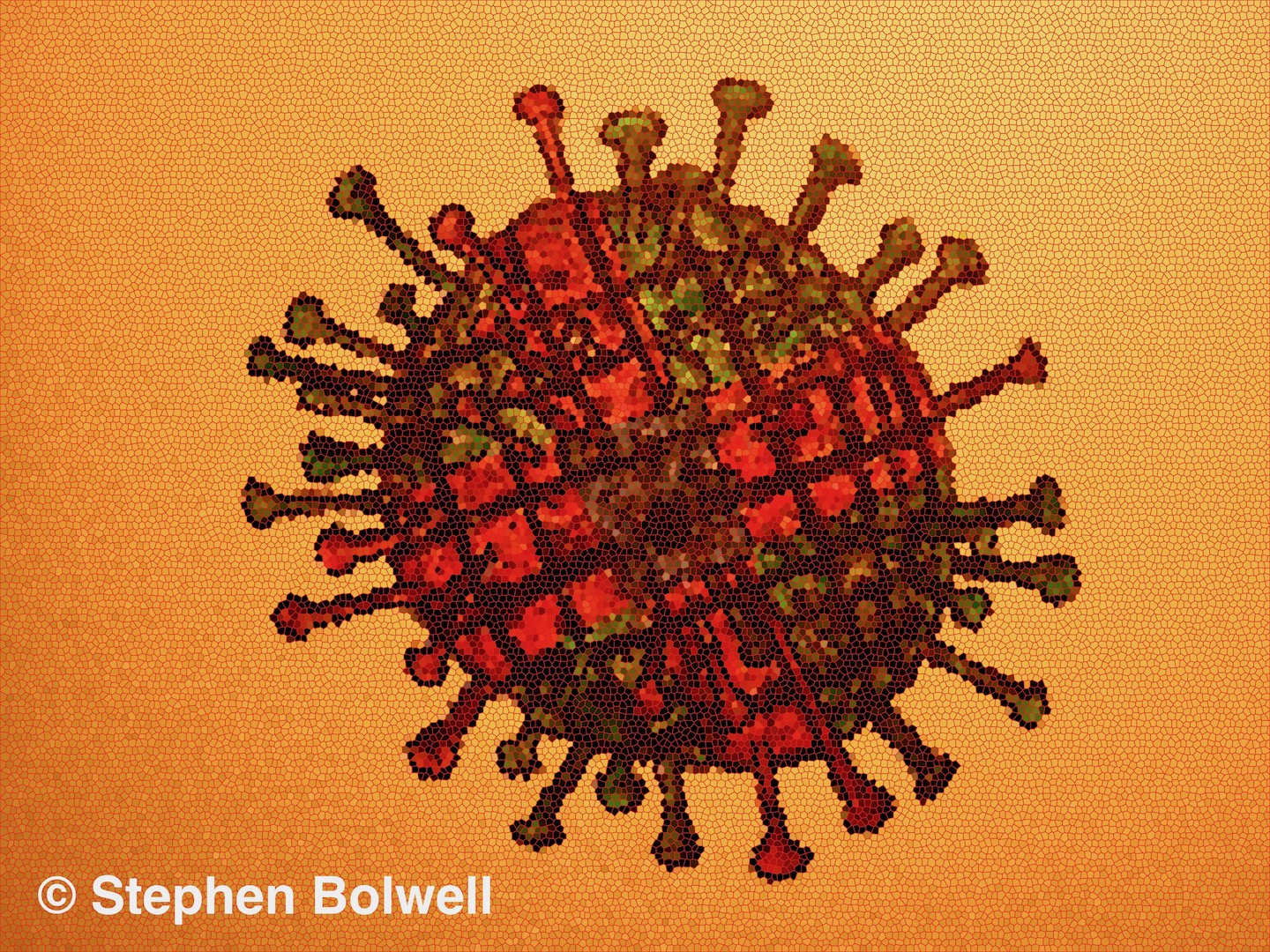

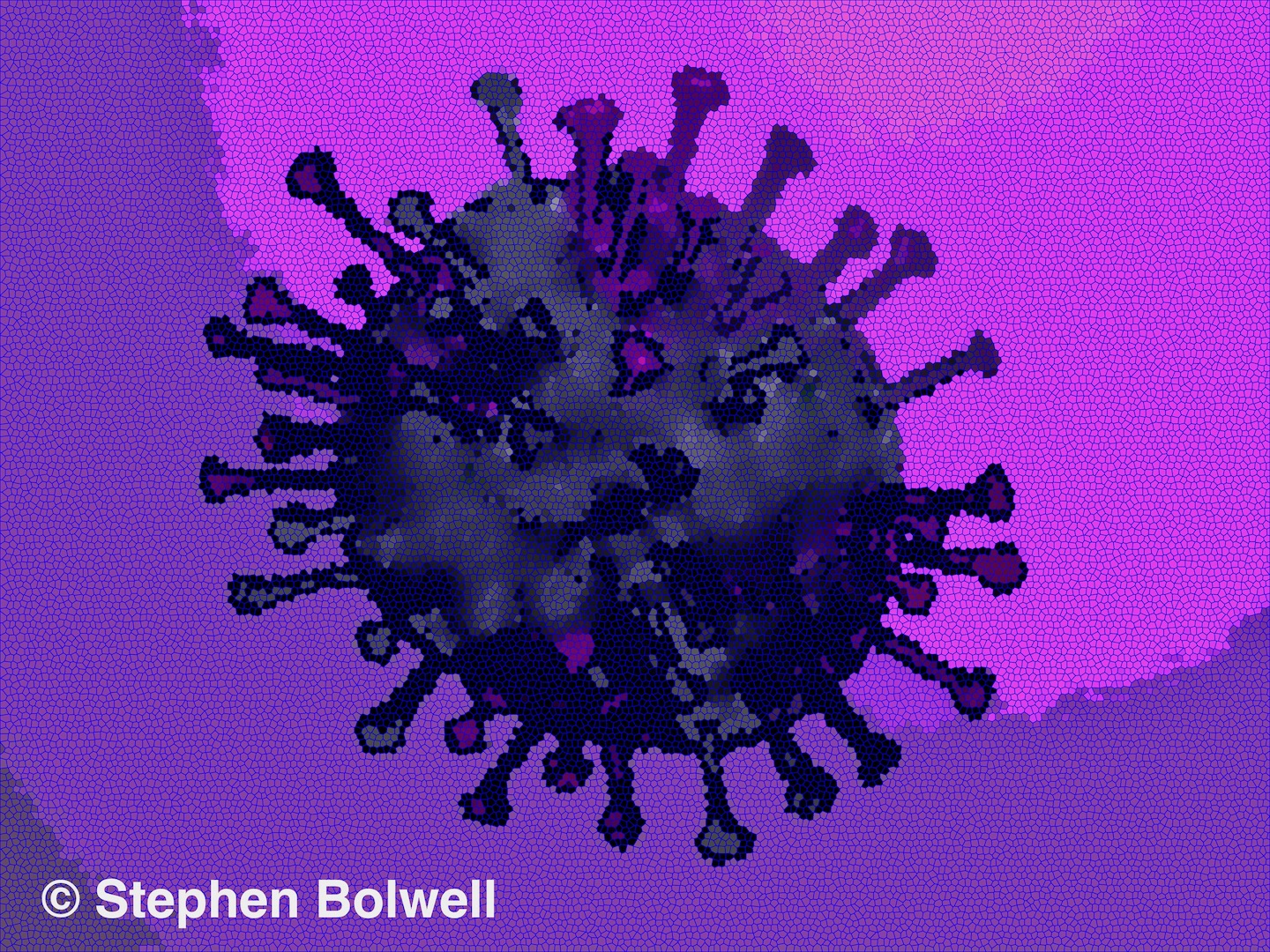

The new infection would soon to be taken seriously enough to be given its own name, COVID-19, officially known as ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2‘, or SARS-CoV-2 because it is related to the first SARS virus – an outbreak of which occurred in 2003. Initial reports suggested that it had ori ginated from a cobra, but snakes are not closely related to our species making them an unlikely source for a human variant; far more likely that it came from a mammal.

ginated from a cobra, but snakes are not closely related to our species making them an unlikely source for a human variant; far more likely that it came from a mammal.

In late February 2020 a research group demonstrated that a coronavirus found in frozen cell samples taken from illegally trafficked pangolins in China shared between 85.5% to 92.4% D.N.A. with the coronavirus that was infecting humans. Another research project came up with a slightly tighter match at around 90%; and yet another study discovered a coronavirus in a bat that shared 96% of its DNA with the human COVID-19 form; but despite a basic awareness of the numerous animal species that carry closely related coronaviruses, nobody knows the precise route the variant took to enter a human host.

When a coronavirus crossed over to become Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS CoV) in 2002-2003, it produced a severe form of pneumonia which probably originated from a live animal market in Guangdong – the bat population from which the syndrome was thought to originate was however only about 1 kilometre from the nearest village and the virus also remains viable for a time in bat droppings and with transmission to other mammals the route it took to enter a human host is still open to question. Nevertheless it rapidly became a problem because humans do not have any developed resistance to new infections that arise from mutated forms that suddenly adopt us as a host.

The SARS virus was found to be present in Rhinolophus bats, the Asian palm civet and a variety of other small mammals – and because of its association with the virus the civet was soon to become persecuted. But wild animals carrying viruses that might cross over to us are not really to blame, especially when they are captured and brought into primitive markets where basic standards of hygiene are a low priority. Here a variety of creatures are brought together in high numbers in cages stacked one upon another bringing together animals, both wild and domestic, that would not usually meet, making it a high probability that COVID-19 originated under these circumstances. China hopes that other nations will not play the blame game, but if novel viral infections are proven to originate from such animal markets and these continue to operate, attitudes to how global trade and travel is conducted must significantly change.

The SARS virus was found to be present in Rhinolophus bats, the Asian palm civet and a variety of other small mammals – and because of its association with the virus the civet was soon to become persecuted. But wild animals carrying viruses that might cross over to us are not really to blame, especially when they are captured and brought into primitive markets where basic standards of hygiene are a low priority. Here a variety of creatures are brought together in high numbers in cages stacked one upon another bringing together animals, both wild and domestic, that would not usually meet, making it a high probability that COVID-19 originated under these circumstances. China hopes that other nations will not play the blame game, but if novel viral infections are proven to originate from such animal markets and these continue to operate, attitudes to how global trade and travel is conducted must significantly change.

SARS is closely related to COVID-19, but it was contained and died out before a vaccine could be developed. Iin 2012 another Coronavirus showed up in humans – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) which once again was thought to be transmitted by bats. Scientists compared the virus surface spikes of MERS-CoV to a related bat coronavirus HKU4 which cannot mediate entry into a human, but only two mutations (on the MERS-CoV spike) were required to enable it to do so, thus enabling the virus to enter a human cell.

Why Bats?

The reason relates directly to the evolution of flight in the order of mammals (Chiroptera). A flying bat has a metabolic rate two and a half to three times the requirements of an active non-flying mammal of similar size. Essentially, flight should be detrimental to a bat’s health – the oxidative stress of a high metabolic rate inducing the release of free radicals which damage DNA. To overcome the toxicity, bats have evolved mechanisms to minimise the problem and also repair damaged DNA; in the process the gene variants involved provide protection by boosting the immune system, allowing bats to carry viruses without serious consequences, which makes them ideal hosts for coronaviruses to inhabit.

The reason relates directly to the evolution of flight in the order of mammals (Chiroptera). A flying bat has a metabolic rate two and a half to three times the requirements of an active non-flying mammal of similar size. Essentially, flight should be detrimental to a bat’s health – the oxidative stress of a high metabolic rate inducing the release of free radicals which damage DNA. To overcome the toxicity, bats have evolved mechanisms to minimise the problem and also repair damaged DNA; in the process the gene variants involved provide protection by boosting the immune system, allowing bats to carry viruses without serious consequences, which makes them ideal hosts for coronaviruses to inhabit.

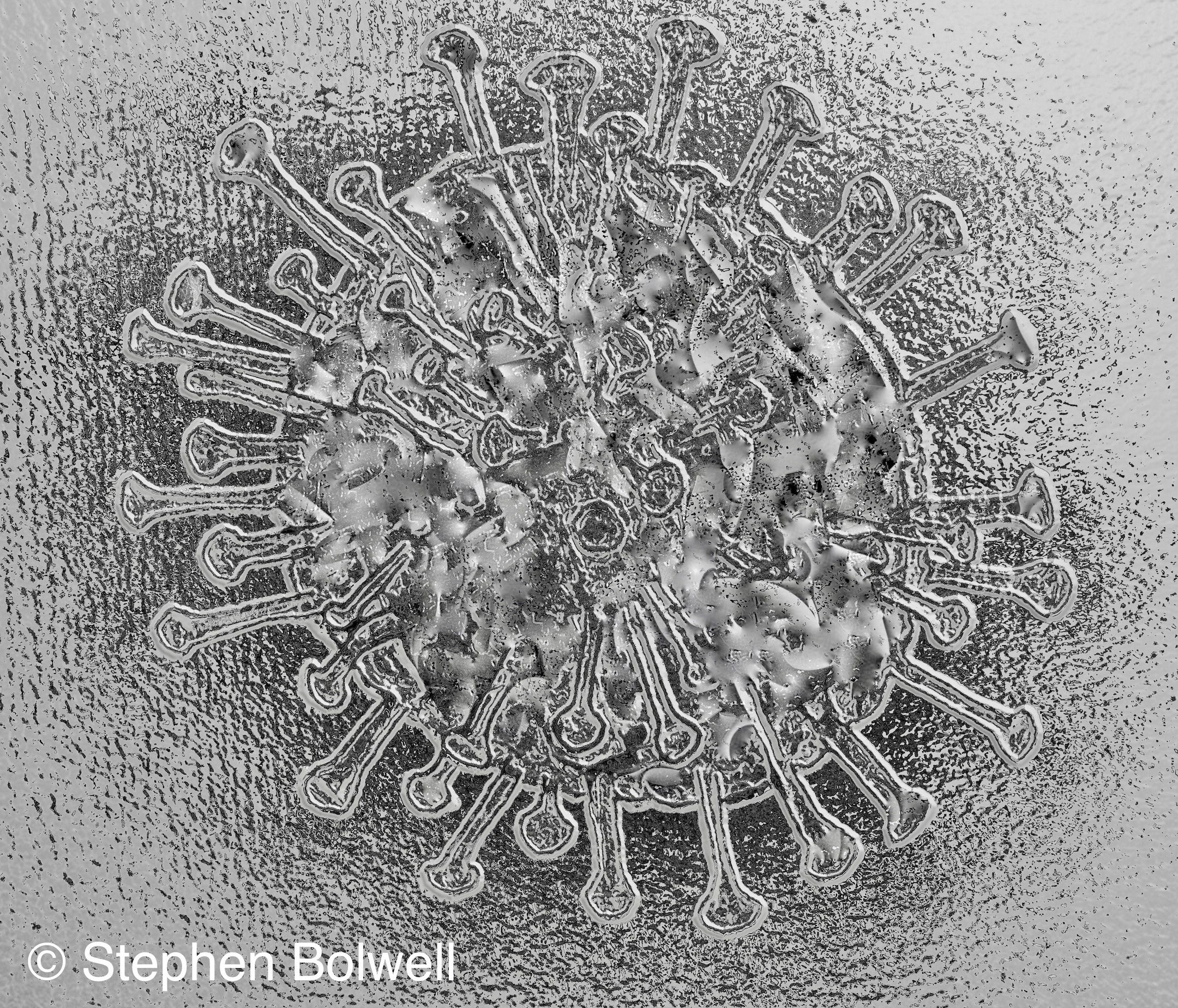

The next question is how does coronavirus get into a human in the first place – what is the physics and chemistry of the process: certainly the spiky surface of the organism is an important part of the story. The virus must firstly get into the respiratory tract of a human, once there it has to enter a cell and this is achieved when the oily layer coating a spike manages to combine with the membrane on a cells surface. If fusion occurs the virus may then enter the cell and mutations of the proteins contained on the spike’s surface are important factors in transmissibility – if everything falls into place the coronavirus will infect its new host.

Knowing this to be a basic mechanism of transmission, the advice we have been given to inhibit the infection now running through the human populations makes sense: washing our hands properly with soap and water along with the use of alcohol wipes and sprays helps reduce COVID-19’s progress by disrupting the oily protein layer on the spikes of the virus and greatly reduces the chances of the organism entering a human respiratory system cell, and in a best case scenario will dissolve the virus membrane rendering it inactive.

Finally, there is the question of how frequently mutations occur: coronavirus has a proof reading enzyme which stops too many mistakes from being made during reproduction, reducing the number of mutations of the relevant protein on the surface of the spike. Because mutations are less frequent it has been difficult for scientists to follow the course of the infection, because it is changes in the virus’s make up that provides markers to indicate where the infection has come from. Not being able to ascertain the route has to some degree hindered attempts to contain the infection; but there is also an up side – unlike flu this viruses does not change regularly which at least makes it predictable and important in the development of a treatment.

Covid-19 is thought to have started in a similar manner to SARS, but in this case originating in a wet market in Hubei province and once established in a human host the new viral disease would soon begin its rapid journey around the world. The first recorded case from China was on the 17th November 2019, and by the 11th March 2020, 122,000 cases had been recorded in 121 different countries. The clever thing about viral infections is that they don’t stay in one place for very long, and unless dealt with in the emergent stage, will sometimes become unstoppable.

Covid-19 is thought to have started in a similar manner to SARS, but in this case originating in a wet market in Hubei province and once established in a human host the new viral disease would soon begin its rapid journey around the world. The first recorded case from China was on the 17th November 2019, and by the 11th March 2020, 122,000 cases had been recorded in 121 different countries. The clever thing about viral infections is that they don’t stay in one place for very long, and unless dealt with in the emergent stage, will sometimes become unstoppable.

If when the disease emerged China had clamped down, the virus might have been contained, but the initial decisions were taken at a local level, and it wasn’t until decisions were made further up the chain of command that the disease was dealt with effectively. With a virus spreading exponentially a day missed can result in thousands of infections. Unfortunately, before the government clampdown in the region where the outbreak started, people were moving off to visit family and friends on their Chinese New Year holidays and initially there were no movement or quarantine restrictions – it was a bad start. For a month very little was done to curtail the disease, and by the time more stringent measures were in place, it was far too late, the disease had taken off and moving elsewhere – the problem no longer containable.

In fairness to China, after a poor start, the country has shown an unrelenting commitment to eradicate the virus, and with impressive results. Back in February it was a different story. On 12th. Hubei reported nearly 15,000 cases of infection, with 242 deaths in a single day – figures were being reassessed, officials were being sacked. On 13th there were 5,000 more cases and another 116 people had died. It was disturbing, and by 18th the total number of infections in Hubei totalled 61,682, with the death toll reaching 1,921.

In fairness to China, after a poor start, the country has shown an unrelenting commitment to eradicate the virus, and with impressive results. Back in February it was a different story. On 12th. Hubei reported nearly 15,000 cases of infection, with 242 deaths in a single day – figures were being reassessed, officials were being sacked. On 13th there were 5,000 more cases and another 116 people had died. It was disturbing, and by 18th the total number of infections in Hubei totalled 61,682, with the death toll reaching 1,921.

At this stage it was difficult to image that things were going to get better, but a month later on 18th March 2020 it was announce that homeland infections in China had been reduced to zero, which is astonishing given the virulence of COVID-19. If the official figures given for the outbreak were considered on the low side, then this only serves to make the present situation all the more impressive. With restrictions becoming less strict in Hubei, the world now waits to see if the virus will make a comeback, and if it does, how it will be dealt with.

As the cradle of the disease China presented an early example of how the disease might progress and South Korea which I mention later, wasn’t far behind and it was important for other countries to watch and learn from these early dealings with the disease.

For some inexplicable reason, many Europe countries and the United States dithered. China and South Korea were far away – maybe it wouldn’t be such a big problem. In the U.S. in particular it was business as usual no matter the warning signs, few preparations were made for what was about to happen and valuable time was wasted.

On 31st Jan 2020. two Chinese tourists tested positive for COVID-19 in Rome; a week later an Italian man returning from Wuhan in China was taken into hospital and became the third case in Italy. Then things took off. The Lombardy region was hit particularly hard and pretty soon growth in the disease would reach an exponential growth rate. Soon there were too many cases for hospitals to deal with; intensive care units were overwhelmed, and the only products being manufactured were coffins.

To list the figures for the next 19 days isn’t necessary. It is a distressing story, a novel disease would produce something more terrible than a work of fiction and by 19th March 2020 Italy surpassed China with 3,400 deaths from Covid-19, with 40,000 recorded cases, 5,322 of them on this one day. The outbreak in Italy put the frighteners on the rest of Europe, and pretty soon things began to look bad in France, German, Britain and especially in Spain.

Almost a week before the COVID-19 was declared a ‘Global Heath Emergency’ a group of news correspondents in the U.K. complacently suggested that the situation was mostly under control, which begs the question: how much do these people really know, or more to the point – how much of what they think they know is wishful thinking? Wherever we are in the world we know these people – they are the same ones that told us Donald Trump was unelectable and Brexit would never happen. People who find it easy to run off at the mouth despite being incapable of critical analysis – they are prepared to offer their thoughts on just about anything without due consideration for their ignorance; in this case, an immunological problem about which they knew absolutely nothing.

Then there are the politicians who’s priorities it seems has been to keep world economies stable, making this a priority over the health of the people who elected them into office. Of course, it would be naive to suggest that economies are not enormously consequential to us all, but the truth about what we are all likely to experience should not be coming in a poor third to financial gain and political self interest. It is of course necessary to reduce the likelihood of panic, but underplaying the science, which so clearly indicates that COVID-19 will most likely become a pandemic requiring a rapid and appropriately reaction is unforgivable. (Obviously, things have moved along since I wrote this. So has there been an appropriate reaction. In many places around the World the answer has to be no).

Clearly the smooth running of our economies is important, but like wars, less important to most individuals than staying alive. If politicians can’t grasp the magnitude of the situation and the disease’s potential because they are incapable of understanding the science and the basic maths that goes along with it, they should listen more closely to what their scientific advisors tell them, even when this is based on models of likely outcomes, as data based decision making is much better than simply guessing, or those other favourites – ‘being hopeful’ and ‘maybe we’ll get lucky’.

There was a point in the disease when many believed that this was just another bout of the flu, so why bother with it? – nature was just clearing out her old sock drawer, but thinking that way was a mistake. The disease is more infectious than flu, moving faster and increasing exponentially over a very short period of time – in some cases doubling every three days – and without a vaccine it could, if unchecked, create total chaos as health services become overwhelmed with patients they will not be able to treat, and with large numbers dying unnecessarily. In many countries there has been inadequate testing for the virus, in consequence knowing exactly how many people are carrying the disease is impossible to estimate because some people show no symptoms. We will of course be aware of the number of people infected in hospitals and the numbers dying because such things are hard to miss; but increasingly it isn’t just the old and vulnerable who are in danger, as younger people are now dying from the infection; and who can say for certain that the virus won’t suddenly mutate and start taking out healthy young economists, the same way it is taking out health workers.

The situation in the USA was sketchy from very early on. On February 26th President Trump was at first dismissive – ‘there were a low number of cases, the people who were ill were getting better and in a couple of days the numbers would be down to zero’. Then on the 28th he said – about those working on the virus – that ‘they’d done an incredible job, and like a miracle it would disappear’. On March 6th he clarified that, ‘anybody who needed a test would get a test and the tests were beautiful’… and they may well have been, but they certainly weren’t available to everybody who needed one.

Rather oddly, on the 20th February when things started to look problematic the President put Vice-President Mike Pence in charge – an individual who thinks Darwin was wrong – a clear indication that this is a man not well versed in science. The President could have appointed an expert medical advisor such as Dr Anthony Fauci The director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; a man already on the task force, but he had spoken out on the lack of preparedness of the administration to deal with the outbreak. A comment made when President Trump closed US airports indicated that the president ‘had shut the chicken coop door after the horse had bolted’ – an interesting mixed metaphor, implying that the President had missed his opportunity to react appropriately. Soon after the President gave himself a perfect 10 out of 10 for his dealings with the coronavirus emergency. A U.S. medical expert quickly responded that 10 out of 100 was nearer the mark.

Rather oddly, on the 20th February when things started to look problematic the President put Vice-President Mike Pence in charge – an individual who thinks Darwin was wrong – a clear indication that this is a man not well versed in science. The President could have appointed an expert medical advisor such as Dr Anthony Fauci The director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; a man already on the task force, but he had spoken out on the lack of preparedness of the administration to deal with the outbreak. A comment made when President Trump closed US airports indicated that the president ‘had shut the chicken coop door after the horse had bolted’ – an interesting mixed metaphor, implying that the President had missed his opportunity to react appropriately. Soon after the President gave himself a perfect 10 out of 10 for his dealings with the coronavirus emergency. A U.S. medical expert quickly responded that 10 out of 100 was nearer the mark.

On a more personal note the air travel announcement came a couple of hours after I’d seen my wife off from Vancouver airport to attend her mother’s funeral in the U.K. she had booked to travel via the USA before the virus went global, and her return flight was cancelled; she then had trouble booking a flight back to Canada. Everything was suddenly moving too quickly for most of us to keep up with. U.S. airports had already been closed to travellers from Europe (understandably so because on that very same day Italy had 250 deaths in 24 hours). Now US air travel was being closed to Britain where the death rate still remained low, but nevertheless doubled on the 14th March. There were then 1,100 confirmed cases of infection in the U.K. but the real figure was estimated to be nearer 10 times that figure. Without testing the general population, it was impossible to say and by 26th March no testing outside of hospitals was still the official policy – probably because there simply aren’t enough kits to facilitate doing so.

South Korea is one of a few exceptions to the general trend, and were able to provide reliable figures fairly early on because they were testing thousands of people. By 11th March the USA had tested 11,000 people, while South Korea was testing 10,000 a day for free, with some reports suggesting this figure was nearer 20,000 a day. Five days later it was reported that South Korea had tested some 250,000 people while the USA had managed only 20,000 in total; which is ironic because on the same day The World Health Organisation (WHO) said, ‘You can’t fight a fire blindfolded. Test, test, test’. The clear implication, being that it is impossible to judge the scope of the problem until you know how many people are infected, and when you have done as many tests as possible, it makes sense to identify all contacts from two days prior to the infected persons first signs of illness and test those people as well. However, the increasing number of infections in many countries was by this time, likely to have passed the point where this could be done successfully; certainly this was the case for the U.S.A. because so few had been tested under a public health service that was poorly funded making the number of infected people difficult to ascertain.

The USA had opted to produce its own testing kits, but there simply weren’t enough of them, and many didn’t work very well. It was as if the U.S. wasn’t serious about dealing with the problem. President Trump seemed preoccupied with protecting the economy and appeared to be saying almost anything to divert attention from the problems that a potential pandemic might have on the money markets, and so the country didn’t react when it should have done. Stock exchange values began to tumble and realising the U.S. was not going to escape fiscal pain the President surprised everybody with a U-turn and on 13th March declared a national emergency.

In Britain as of 25th of March people were not being tested unless they were in hospital, and neither were the medical staff who were treating them (although by the 27th there were promises to do so, as health workers were quite reasonably, showing concern). But those who though they had the virus were still being told to go home and self isolate and were unable to get tested by a doctor. To say Britain has been ill prepared for this emergency is an understatement. On 26th March Mayor Giorgio Gori of Bergamo in the Lombardy region of Italy said that Britain had got it wrong – with infection rate two weeks behind Italy, it had been too slow to react which might cost many lives.

In the USA critics considered the administrations reaction to COVID-19 to be all over the place and the markets continued to be volatile. It was Jo Biden (the most likely candidate to stand against President Trump in the Presidential election of November 2020) who on 12th March steadied the ship, with a speech that probably should have been made by the president; and you have to wonder if the electorate will remember the disorganised nature of the current administration’s handling of this national emergency when it comes to November… if the election still happens. On 26th March President Trump was still hopeful of getting people back to work – a couple of days previously he had suggested that could be by Easter, but set against the news on 26th March, that the USA had 83,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, overtaking all other countries to become the epicentre of the pandemic, getting back to work seemed the least of its problems. By the 28th New York was pleading with the government to get started on making respirators as they needed them urgently. The president thought that such provisions were better coming from private industry, but N.Y. needed them urgently…and I wonder how many political turning points you can have as this will to come back to haunt the president if there are people dying through lack of respirators.

The country had plenty of time to consider the seriousness of the developing situation, but still appeared woefully ill prepared. Looking beyond COVID-19, we might ask whether many of our leaders will persist with exactly the same approach to global climate change, and continue with the usual resistance to scientific evidence, inhibiting our ability to react appropriately, and we find ourselves in yet another dire situation of a different making.

The only positive thing to come from the pandemic is a slowing of industrial productivity, leading to a rapid reduction in carbon and other emissions with the consequence that many of us are experiencing much cleaner air. Aerial views of major cities worldwide demonstrate that pollutants have largely disappeared from areas that a few months ago were experiencing serious air quality problems – with some of this the result of a recent reduction in air travel. However, the global pandemic is co-incidental to our climate problems, and probably isn’t the most appropriate way to reduce Carbon emissions.

COVID-19 has demonstrated clearly, that we might be incapable of reacting quickly any big problems that occur on a global scale; as by the time we do, they are out of our control. Just as with climate change, we are too often simply hoping for the best, while our leaders react too slowly to scientific evidence available, in deference to short term economic gain; and if that continues, such actions will not save our economies, but inevitably lead us to a far more precarious future.

I am aware the COVID-19 pandemic has caused suffering in a great many countries and I regret that I have not been able to follow all of them; certainly I should have given more attention to Spain where the virus has taken hold. As I finish writing on 27th March, although the infection rate in Spain has slowed, the number of deaths today totalled 769. Unfortunately the country did not lock down quickly enough and testing for the virus was not adequate.

Around the world the COVID-19 story is changing by the hour, with India now coming into the story: this country has the second highest population in the world – and with people living in close proximity to one another, self distancing is difficult to achieve. Dealing with the virus under such circumstances is a monumental task; nevertheless on 24th March Prime Minister Narendra Modi put the country on lockdown for 21 days in an effort to get to grips with the virus at a relatively early stage when infection rates might still be manageable. It remains to be seen whether India can succeed where other countries have failed. Whatever the case, the World must now act together in solidarity because for the first time in living memory, we are all in this together. On the evening of 28th March Prime Minister Boris Johnson who the previous evening had tested positive for the virus (as was the case for his Health Secretary and Chief Medical Officer), announced a lockdown in Britain; and critics of policies that had previously seemed too vague for many Britains to follow were saying, ‘better late than never’.

Stephen,

I hope you and your family are well. I also almost left for the UK to visit Dad but that will now have to wait.

Thank you very much for the very informative article about COVID -19.

It’s amazing how a minuscule virus has and will change the course of history. The next fight after climate change will be the issue of the trade in wild animals and plants. I see the Chinese and impoverished locals are logging the last of the rosewood stands in Mali and Senegal, all to make high-end furniture. Madness!

Thanks John. I was going to visit my father in the U.K., he is 97 and lives alone. However, Air Canada cancelled my flight and still have my money – their policy is no refund and I am sure a great many other people are now thinking they could have made better use of their money in the present situation. Not that many of us would consider flying now – I booked long before there was a COVID-19 problem.

The rosewood story is a frightening one – the BBC covered it very well. I try not to be too critical of any country, but the Chinese appear to come up again and again in a poor light in relation to environmental issues. Nevertheless, I haven’t taken sides when it cones to the pandemic story; if we look coldly at the present COVID-19 figures, it is clear there are serious questions to be asked about how our country of origin (the U. K.) has dealt with the virus, particularly in regard to testing – there can be no absolute measure of how many people are infected without it. Those countries testing as a priority have done much better than those that have not. The U.S. appears to be all over the place with policy and the result of this will be reflected in their COVID-19 infection and mortality figures. I have become interested in how much we can deduce for ourselves from figures that are publicly available and will soon be posting, ‘Covid-19. Simple Arithmetic and the Economy First Delusion’. The next question we should be asking is: when the crisis is over, will we be returning to the old ways, or has the World changed forever?