I’d like to think that the most democratic countries have been the best at controlling COVID-19, but this would not be true, although there is no doubt that China did a great job at under reporting the severity of its outbreak, claiming that any suggestion that this was a problem originating out of China as racist. There was little about the way China reported on its outbreak that would help other countries to prepare.

I’d like to think that the most democratic countries have been the best at controlling COVID-19, but this would not be true, although there is no doubt that China did a great job at under reporting the severity of its outbreak, claiming that any suggestion that this was a problem originating out of China as racist. There was little about the way China reported on its outbreak that would help other countries to prepare.

In the U.K. by 8th April over 60,000 had tested positive for COVID-19, with more than 7,000 deaths as a result of the virus. At the peak of the problem the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson was taken into intensive care, and the good news is that he is showing signs of improvement. It is a little over a couple of months since the first confirmed case in Britain and today alone there have been 938 hospital deaths with 5,492 new cases announced; although there is a claim that infection numbers have increased because more people are now being tested… and a fair response to that would be: testing? Not before time.

This is a very different world from the one where we were wishing our friends a happy 2020 back in January. For many of us, staying at home has so far been voluntary, but last weekend it was sunny and springlike in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere and against official advice quite a numbers of people were out and about with a minority of Brits refusing to conform to anything that felt like an intrusion of personal freedoms. They knew that if they went out for a wander, nobody was going to shoot them – which is a pity: and I’ll leave that sentence as it is… ambiguous. Unfortunately, some things don’t change – there will always be people who don’t have the discipline to act appropriately, and potentially set back the slowing of COVID-19 infections.

This is a very different world from the one where we were wishing our friends a happy 2020 back in January. For many of us, staying at home has so far been voluntary, but last weekend it was sunny and springlike in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere and against official advice quite a numbers of people were out and about with a minority of Brits refusing to conform to anything that felt like an intrusion of personal freedoms. They knew that if they went out for a wander, nobody was going to shoot them – which is a pity: and I’ll leave that sentence as it is… ambiguous. Unfortunately, some things don’t change – there will always be people who don’t have the discipline to act appropriately, and potentially set back the slowing of COVID-19 infections.

France, has a similar problem: on the 7th of April the lockdown became more severe – the first case in France occurred a little over 10 weeks ago, but by the 7th April the death toll had passed 10,000. That was the figure for Italy almost a week ago and there are claims that the French figures have been distorted, with numbers far higher than official figures. France is now one of the hardest hit European countries. Spain’s death toll has passed 14,000, although both Italy and Spain appear to be at the point where infections are beginning to slow.

But how did South Korea, one of the earliest countries to be hit by the virus, manage the disease so much better than many of the Europe countries, limiting the disease so far, to less than 10,500 infections and 200 deaths. This might well have been aided by experiencing an outbreak of the MERS virus in 2018, but more likely it is down to the way things are organised in South Korea. The country has a very good healthcare infrastructure which isa plus; and there is a centralised control of decision making and that has been key to getting things done. The country tracked infected citizens in an authorised manner by monitoring locations for cell phones and credit cards. We are told in the west that such a thing would be impossible, unless of course somebody is trying to sell us something, but when done for public health reasons it is an infringement of personal liberties.

But how did South Korea, one of the earliest countries to be hit by the virus, manage the disease so much better than many of the Europe countries, limiting the disease so far, to less than 10,500 infections and 200 deaths. This might well have been aided by experiencing an outbreak of the MERS virus in 2018, but more likely it is down to the way things are organised in South Korea. The country has a very good healthcare infrastructure which isa plus; and there is a centralised control of decision making and that has been key to getting things done. The country tracked infected citizens in an authorised manner by monitoring locations for cell phones and credit cards. We are told in the west that such a thing would be impossible, unless of course somebody is trying to sell us something, but when done for public health reasons it is an infringement of personal liberties.

Obviously, the South Korean approach would not work everywhere, and in the long term the disease will re-emerge because so few people have so far been infected – you can’t have it all ways; but if anything is to be learnt from this method, it is that a TEST, TRACE and QUARANTINE policy really does work, although many other countries have failed to do this effectively. The best part of the story is that when things started to go badly wrong, South Korea put scientists in charge, and once clear on what needed to be done they acted swiftly, without any kick back from members of the public advocating all the various alternatives to science based decision making. Alternatives to common sense might be absorbed under normal circumstance, but when thousands of people’s lives depend upon governments making reliable decisions on a daily basis, there’s no time for nonsense; and any fool that refuses to make minor short term lifestyle changes to allow others to stay alive, demonstrates about as much discriminatory ability as the virus that the authorities are trying to contain.

Obviously, the South Korean approach would not work everywhere, and in the long term the disease will re-emerge because so few people have so far been infected – you can’t have it all ways; but if anything is to be learnt from this method, it is that a TEST, TRACE and QUARANTINE policy really does work, although many other countries have failed to do this effectively. The best part of the story is that when things started to go badly wrong, South Korea put scientists in charge, and once clear on what needed to be done they acted swiftly, without any kick back from members of the public advocating all the various alternatives to science based decision making. Alternatives to common sense might be absorbed under normal circumstance, but when thousands of people’s lives depend upon governments making reliable decisions on a daily basis, there’s no time for nonsense; and any fool that refuses to make minor short term lifestyle changes to allow others to stay alive, demonstrates about as much discriminatory ability as the virus that the authorities are trying to contain.

In many places in the world, you might think that things can’t get worse, but not if you live in the U.S.A.. It is difficult to find a better example of what dithering can achieve when dealing with a rapidly spreading viral infection; a problem largely ignored during the early stages of the outbreak. In the U.S. there are necessary checks and balances to ensure democracy, but when decisions have to be made at both Federal and State level, results often lack a co-ordinated approach, and during a rapidly moving emergency as is the case with COVID-19, things don’t always go smoothly. Lacking almost any form of control, the virus sensed its freedom and quickly took off. It didn’t have a green card, but moving so fast, easily avoided apprehension. The virus just wasn’t tested and in consequence the U.S. is on the same trajectory for the infection as Italy was a few weeks ago, and will certainly pass it, which to say the least is unfortunate.

The U.S. has experienced a broad range of criticism over its dealings with the pandemic. Florida disease expert Dr. Dena Grayson made the point that the first case of Covid-19 in South Korea occurred on exactly the same day as the first case in the U.S. Jan 20th 2020. While South Korea had its first tests for the disease approved in a week, the U.S. spent most of February wasting time. Countries that have got onto testing early and in high numbers, have been winning the battle because they have a handle on what they are dealing with: knowing who is infected, the rate of infection, and where it is occurring allows the disease to be targeted. Acting without testing is like stumbling around in the dark; worse than that, it is like stumbling around in the dark in the Dark Ages… Getting testing up and running in the U.S. has been slow, and contributed to the spread and general lack of control of the virus in many parts of the country. But more recently President Trump started talking less about the economy and getting people back to work, and more about dealing with the virus, when previously he had down played the problems – hopefully this won’t have come too late to make a difference.

The U.S. has experienced a broad range of criticism over its dealings with the pandemic. Florida disease expert Dr. Dena Grayson made the point that the first case of Covid-19 in South Korea occurred on exactly the same day as the first case in the U.S. Jan 20th 2020. While South Korea had its first tests for the disease approved in a week, the U.S. spent most of February wasting time. Countries that have got onto testing early and in high numbers, have been winning the battle because they have a handle on what they are dealing with: knowing who is infected, the rate of infection, and where it is occurring allows the disease to be targeted. Acting without testing is like stumbling around in the dark; worse than that, it is like stumbling around in the dark in the Dark Ages… Getting testing up and running in the U.S. has been slow, and contributed to the spread and general lack of control of the virus in many parts of the country. But more recently President Trump started talking less about the economy and getting people back to work, and more about dealing with the virus, when previously he had down played the problems – hopefully this won’t have come too late to make a difference.

Certainly things are fairly dire with 10,000 deaths by 6th April. On 8th April 8th the daily figure for deaths in New York state alone hit 799, with almost 2,000 Americans across the country dying on a single day… The same day President Trump swung back to his old approach as he made further comments about opening up the country for business, His advisers said that it was far too soon to loosen up restrictions, and are waiting to see what the President will say next; and it probably isn’t unfair to say that his message on the COVID-19 crisis has become increasingly erratic.

The U.K. like many other places around the world has gone for the personal distancing and isolation for those who are vulnerable or display symptoms, but early on, there was a more relaxed approach. The suggestion was that if enough people were to become infected, ‘herd immunity’ would slow the rate of infection and with less people available to infect, and the infection would drop away; but it soon became clear that with more people getting ill, the health service was likely to become overwhelmed. Britain already had the example if Italy, which was well ahead of other European contries with its stage of infection; and at home intensive care really did mean intensive and often prolonged care, which would become unsustainable as the number of cases increased. It was apparent that some countries had too few respirators and difficult decisions were being made on who lived, and who died. This didn’t go unnoticed by British politicians and there was a sudden change of policy. Maybe there really was an awareness that once an infection rate starts to climb the steep end of an exponential growth curve, ‘things fall apart’ but the decision making might have been more complicated than that, although if they just followed the science it probably didn’t need to be.

The U.K. like many other places around the world has gone for the personal distancing and isolation for those who are vulnerable or display symptoms, but early on, there was a more relaxed approach. The suggestion was that if enough people were to become infected, ‘herd immunity’ would slow the rate of infection and with less people available to infect, and the infection would drop away; but it soon became clear that with more people getting ill, the health service was likely to become overwhelmed. Britain already had the example if Italy, which was well ahead of other European contries with its stage of infection; and at home intensive care really did mean intensive and often prolonged care, which would become unsustainable as the number of cases increased. It was apparent that some countries had too few respirators and difficult decisions were being made on who lived, and who died. This didn’t go unnoticed by British politicians and there was a sudden change of policy. Maybe there really was an awareness that once an infection rate starts to climb the steep end of an exponential growth curve, ‘things fall apart’ but the decision making might have been more complicated than that, although if they just followed the science it probably didn’t need to be.

The virus was a little slower getting to some parts of the world; and this was the case for Nigeria, where preparations were being made long before it arrived; especially in Lagos, which has around 20 million inhabitants, and is the most populated city in Africa.

The virus was a little slower getting to some parts of the world; and this was the case for Nigeria, where preparations were being made long before it arrived; especially in Lagos, which has around 20 million inhabitants, and is the most populated city in Africa.

In the capital city, one in three households live in poverty which makes dealing with any contagious disease difficult. This is true for any country that has large numbers of people living in close proximity to one another with poor sanitation, problems with clean water, and otherwise difficult conditions. In such places COVID-19 could prove devastating as local infrastructures prove inadequate when dealing with such a virulent disease. There is also a high probability that such locations could become reservoirs for COVID-19, with outbreaks continuing for years into the future.

We learn from every viral infection that has gone before. In 2009, a new flu virus emerged and was given the name (H1N1)pdm09, it would became a pandemic. This flu variation showed up in a form quite different from the H1N1 virus that had been circulating previously, but despite the differences older people appeared to have some immunity to it, perhaps because of previous exposure to the H1N1 virus earlier in their lives, and the disease would primarily infect younger people who had not had the same exposure to the H1N1 virus. Retrospectively, we can see trends with most viral diseases, but when a new one crops up, or returns in a slightly different form, it can be difficult to predict outcomes. One of the options is to closely watch a disease in its early stages, and extrapolate the numbers that the course of infection throws up and act accordingly.

Flattening the Curve.

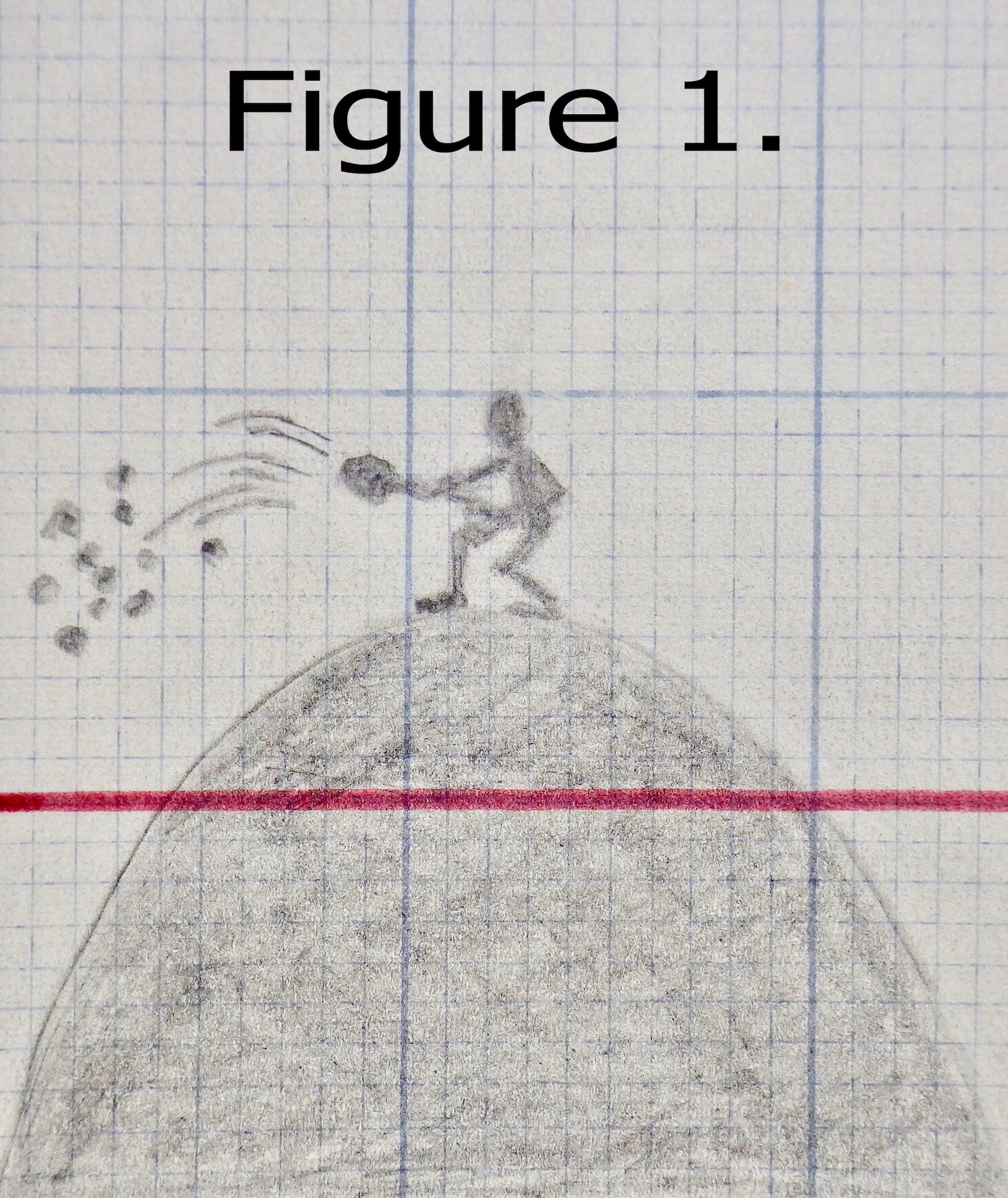

With infections of COVID-19 doubling every three days both in the U.K. and elsewhere it became clear that if the virus was allowed to run its course without resistance it would overwhelm health services and make dealing with the virus impossible. The solution was to flatten the curve. i.e. to spread the number of infections over a longer period of time to avoid losing control. The policy required people to wash their hands, keep a distance from one other, and for the most vulnerable and the infected to self-isolate for several weeks, thus starving off opportunities for the infection to reach a new hosts. In Figure 1 an individual works away to flatten the curve. Above the red line, high numbers of infections will overwhelm the health service in a short period of time and put hard pressed health workers at greater risk of infection.

With infections of COVID-19 doubling every three days both in the U.K. and elsewhere it became clear that if the virus was allowed to run its course without resistance it would overwhelm health services and make dealing with the virus impossible. The solution was to flatten the curve. i.e. to spread the number of infections over a longer period of time to avoid losing control. The policy required people to wash their hands, keep a distance from one other, and for the most vulnerable and the infected to self-isolate for several weeks, thus starving off opportunities for the infection to reach a new hosts. In Figure 1 an individual works away to flatten the curve. Above the red line, high numbers of infections will overwhelm the health service in a short period of time and put hard pressed health workers at greater risk of infection.

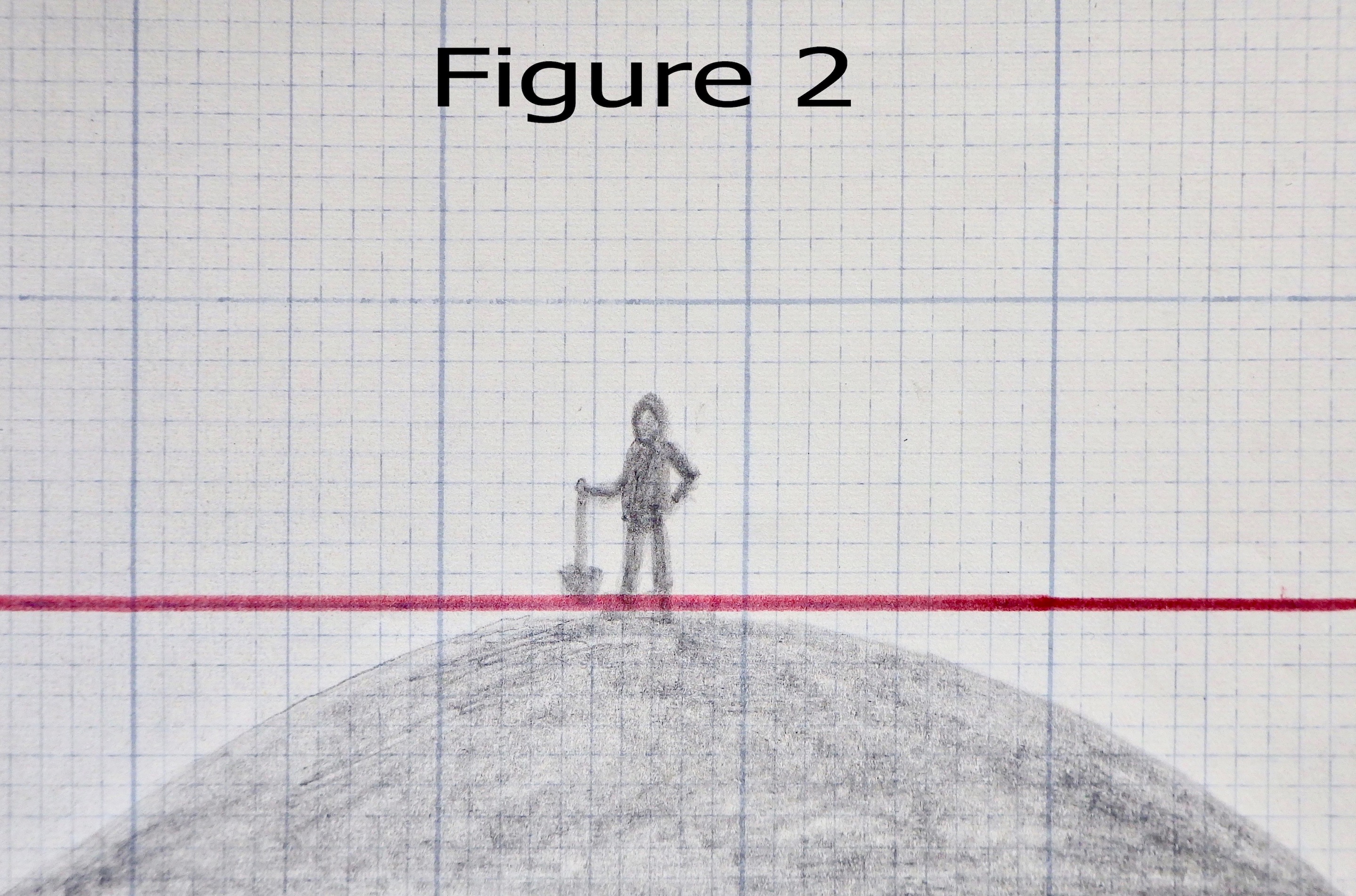

If the number of infections can be spread, keeping the curve below the red line as in Figure 2, the load will be reduced and make dealing with the disease more manageable.

If the number of infections can be spread, keeping the curve below the red line as in Figure 2, the load will be reduced and make dealing with the disease more manageable.

On 20/3/20 bars and restaurants were closed in Britain encouraging people to keep their distance from one another – stay at home was the message. But around the world not everybody was listening to government advice. On the other side of the world large numbers of people were out and about in close proximity, enjoying themselves on Bondi beach. Perhaps embarrassed by the publicity, the New South Wales authoritie -, within a few hours of the story emerging – closed beach access. Then came the news that the day after tighter restrictions in the U.K., people had responded by going out in Bank Holiday numbers to beaches all around Britain, with Brighton, Bridlington and Skegness especially busy. People were also travelling from heavily populated areas to remote locations such as the Highlands of Scotland in an attempt to escape the virus, potentially bringing the disease with them. Initially the message wasn’t getting through – clearly some people weren’t taking the crisis seriously and valuable days were lost while government went about trying to provide a clearer message on why in the short term a lifestyle change was necessary. By the beginning of April a sunny weekend became irresistible for some, and ‘the rules’ might need to be more rigorously enforced in future, especially at Easter, when the continued efforts of the majority could so easily be compromised.

Maybe there’s a simple way to explain why we all have to modify our behaviours to combat COVID-19, because when simple arithmetic begins to look like maths, nobody wants to know, although in the U.S. it’s math, which makes it even more singularly dull. So, consider a hypothetical viral disease similar to COVID-19: the number of people infected by the disease doubles every three and a half days and it is most infective during the first week after entering a new host, where it gets busy shedding rapidly to optimise the chances of entering other hosts. Under these circumstances a person infected by the disease will infect two other people over the course of a week, and those two people will each infect two others during the second week, and so on as the disease progresses.

For no better reason than vulnerable people in Britain have been advised to isolate themselves for three months, let’s run the course of the disease over the same period and assume a vulnerable person comes out of isolation on week 13. If I was superstitious I’d describe this as the unlucky week, especially if the vulnerable person was to meet up with a ‘couldn’t care less infected individual running in a direct line of transmission from the original source.

Here’s how it goes: Harry is a bit of a twit and doesn’t like following rules; against government advice he’ll take his chances of getting infected. Harry is out and about and he doesn’t care: on the beach one day, in the park another, and drinking with friends in social gatherings. He has the virus in his system but shows no symptoms – the surprise is he infects only two people during his first week of carrying the disease and that’s how things start.

Here’s how it goes: Harry is a bit of a twit and doesn’t like following rules; against government advice he’ll take his chances of getting infected. Harry is out and about and he doesn’t care: on the beach one day, in the park another, and drinking with friends in social gatherings. He has the virus in his system but shows no symptoms – the surprise is he infects only two people during his first week of carrying the disease and that’s how things start.

Over the course of twelve weeks Harry’s indifferent behaviour sets off a a progression of infections for which he is the only source; the infection of other individuals progresses week by week starting from the initial 2 infections in the first week, which creates 4 infections the second week, and so on. 4 becomes 8, 8 becomes 16 then 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, and by the unlucky 13th week, Harry has been responsible for 8,192 infections. Fortunately, the death rate is only at 1% of those infected – I have been generous because The World Heath Organisation gives a figure of 3.4% for COVID-19, but I’m thinking it might not be that high because there must be a lot of people infected who are not aware, due to a general lack of testing in so many places; and there must be a good numbers of people walking around who never get to a hospital. So, with the theoretical disease Harry has killed only 80 people and that’s well above what most serial killers will manage. Infact you’d probably have to go to war to kill that many people and get away with it. If it was as high as 3.4% Harry would be responsible for the deaths of 272 people

What if you were as irresponsible as Harry but you infected 3 people in a week rather than two, and things went on at that rate, tripling up rather than doubling up – a transmission rate that by some estimates would be low for Covid-19. The series would run: 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 288, 864, 2,592, 7776, 23,328, 69,984, 209,952 and if things went on another week, that would push the figure up to nearly half a million. With a death rate of 1% over just the 13 weeks there would be over 2000 people dead. What if 4 people were infected each week?… Perhaps it does make sense to avoid other people for a while…

What if you were as irresponsible as Harry but you infected 3 people in a week rather than two, and things went on at that rate, tripling up rather than doubling up – a transmission rate that by some estimates would be low for Covid-19. The series would run: 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 288, 864, 2,592, 7776, 23,328, 69,984, 209,952 and if things went on another week, that would push the figure up to nearly half a million. With a death rate of 1% over just the 13 weeks there would be over 2000 people dead. What if 4 people were infected each week?… Perhaps it does make sense to avoid other people for a while…

I will admit to a hole in this model. There will be people not going out in an effort to avoid Harry and other people like him, and so the more people who are behaving responsibly the less contacts Harry will make, but nevertheless amongst Harry’s friends, it isn’t too difficult to infect 2 people over the course of a week. Nevertheless, people distancing themselves from others will starve the disease and the number of people catching the virus will drop significantly. This is the reason models come in for so much criticism, they appear to be all over the place, with the predictive number of infections varying from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands, this not because the model is wrong, but because figures can change dramatically when small changes are made early in the progression of the disease. If we don’t get our behaviours right, the number of infections possible are sobering and demonstrates that simply doing the right thing can make a huge difference; and my figures might be regarded as low – to keep things simple I’ve only considered the number of new infections at the end of the 13 week period and not added in all the previous infections as the process moved along ( i.e. the overall total infection number). The same is also the case for the number of deaths.

I will admit to a hole in this model. There will be people not going out in an effort to avoid Harry and other people like him, and so the more people who are behaving responsibly the less contacts Harry will make, but nevertheless amongst Harry’s friends, it isn’t too difficult to infect 2 people over the course of a week. Nevertheless, people distancing themselves from others will starve the disease and the number of people catching the virus will drop significantly. This is the reason models come in for so much criticism, they appear to be all over the place, with the predictive number of infections varying from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands, this not because the model is wrong, but because figures can change dramatically when small changes are made early in the progression of the disease. If we don’t get our behaviours right, the number of infections possible are sobering and demonstrates that simply doing the right thing can make a huge difference; and my figures might be regarded as low – to keep things simple I’ve only considered the number of new infections at the end of the 13 week period and not added in all the previous infections as the process moved along ( i.e. the overall total infection number). The same is also the case for the number of deaths.

We could get bogged down with many other aspects of the disease, but for our purposes, all we essentially need to know is the rate of infection, which to some degree depends on how infective the virus is and how we might reduce its spread by our good behaviours. It would obviously be useful to know exactly who is infected and what percentage of the infected are dying, but beyond knowing how many people are behaving irresponsibly, most of the figures are out there, and it’s up to our governments to assess them and implement effective policies to reduce the number of infections and deaths as effectively as possible. We essentially are just the fuel in the equation – numbers on the graph – and need to stay off of the page if we possibly can.

Test, test, test has been the mantra of the World Heath Organisation, and some governments have been hopelessly ineffective at doing so (Ontario has the highest number of cases of COVID-19 and the lowest testing rates of all the Provinces in Canada…. Is that a coincidence?). In so many countries, as individuals, we need to stay out of circulation for a while – it’s the very least we can do for medical staff who’s lives we put at risk when failing to do so. Staying indoors for most of the day is inconvenient, but it’s better than being dead or causing the death of others.

Saving the Economy Versus Slowing the Disease – Let’s Look at It Another Way.

There’s a pilot with a dilemma. He has taken a small party of people to do business in a remote area of jungle and has to fly them home in a light aircraft. The plane takes off with everybody on board, but pretty soon the aircraft’s engine begins to misfire and the pilot wonders if he should perhaps land on one of the occasional small airstrips still available below and fix the engine; but he knows the businessmen need to get back, and so he flies on. Suddenly the engine begins to misfire very badly and the pilot reconsiders what he should do because the airfields are beginning to thin out now; but he thinks first and foremost of the businessmen knowing he must get them back to their busy lives of doing business and he flies on. But, he hasn’t flown much further when he begins to notice that there are now fewer airfields below just as the engine suddenly catches fire and begins to fail. By great good fortune the pilot sees one last airfield up ahead… he knows exactly what he must do…… he flies on.

For those entrusted with saving the economy it should be apparent that when dealing with an exponentially growing threat, the best policy is to fight that threat as early as possible, never underestimating the power that could be unleashed if you don’t, because when that happens, the price can be very high.

And maybe it’s worth remembering that money isn’t real, it’s value depends on whatever we convince ourselves it’s worth, whereas death isn’t negotiable. It might be that we have to adjust our economies to line up with the natural circumstances we are all living through, instead of allowing the majority to suffer when the loan sharks decide that it’s payback time. Once through the pandemic we might be forced to live in ways that are less damaging to the environment, even though history demonstrates that major disasters do not in the long term halt our Carbon emissions; and there is no guarantee that the future will demonstrate that we have learnt anything useful from the problems we are now facing.

And maybe it’s worth remembering that money isn’t real, it’s value depends on whatever we convince ourselves it’s worth, whereas death isn’t negotiable. It might be that we have to adjust our economies to line up with the natural circumstances we are all living through, instead of allowing the majority to suffer when the loan sharks decide that it’s payback time. Once through the pandemic we might be forced to live in ways that are less damaging to the environment, even though history demonstrates that major disasters do not in the long term halt our Carbon emissions; and there is no guarantee that the future will demonstrate that we have learnt anything useful from the problems we are now facing.

I appreciate the hardship caused to people who have been prohibited from working, but in part this situation is the fault of the many governments that have let things ride, hoping they could get away with it. They pushed their luck and they failed.

I appreciate the hardship caused to people who have been prohibited from working, but in part this situation is the fault of the many governments that have let things ride, hoping they could get away with it. They pushed their luck and they failed.

In fairness, COVID-19 is new to us and nobody can be absolutely sure at which point we might have done better as we were passed through it; but the figures should have provided at least an inkling, and at times it seems as if many minds have been busy elsewhere.

We haven’t been dealing with some abstract existentialist threat: just like the world’s airlines, this has been a grounded event – an exponentially growing disaster with nothing hidden from view. If only more politicians had recognised the danger signs earlier than they have, because many of the answers were sitting there quietly in the arithmetic – just waiting to be discovered.