The other day my son said I was passionate about things; which seemed odd, because I don’t remember being passionate about very much. “With regards to what?” I asked. “Stuff”, he responded waving his hand in the general direction of a bookcase, politely avoiding the word obsessive. Clearly I have a fondness for books…. and quite a lot else.

I find the design of paper cups quite interesting… My daughter, realising I like the kind of things that most people don’t want, also had something to say about the subject, in particular the amount of space that stuff takes up. Her main point was, ‘Young people, don’t hang onto very much these days because they have nowhere to put it’. Buying or renting a property is so expensive, that if you didn’t purchase a home sometime in the distant past, you’re now probably living in what in my youth was a cupboard; I have some sympathy with this, having lived as a student in London in various interesting cupboards. Today, more people than ever live a ‘limited space lifestyle’ and reduce their possessions accordingly — the bare minimum is a mobile phone and a charger — everything imaginable living in the former; with the convenience of discovery entirely dependent on the latter.

If our attitudes towards ‘space’ in relation to the natural world had progressed as quickly as technology, we’d all be living in a very different world. The doubling time for human population is presently around 50 years, and it has become fashionable to kick back at any suggestion that this might be a problem. Perhaps it is possible to get everybody in the World into just one major city, but that’s a bit like saying you can pack a great many sardines into a tin; it’s a mathematical consideration relating to volume, and not a measure of viable lifestyles. Without doubt, humans require enormous resources, especially in the developed world. In a very short time we have taken over vast swathes of natural space, creating problems for species that cannot, and never will, be able to adapt to such rapid environmental changes.

A recent report on wildlife populations worldwide, indicates that there has been an average decline of 69% since 1970; during that time the U.K. is thought to have lost 50% of its biodiversity, which is startling to me, because I remember being told as a teenager in the 1960s of similar concerns over the losses that had occurred since the 1930s.

At the time of writing, a new 5 part David Attenborough series ‘Wild Isles’ featuring wildlife in Britain is about to air on BBC television. An episode 6 exists dealing with the stark loses of wildlife in the U.K. and the causes, but this programme will not be broadcast as part of the series for fear of a right-wing backlash, and available only on iPlayer. One poll in 2006 voted David Attenborough ‘The most trusted celebrity in Britain’, and in any event it is unlikely that Sir David would say anything that wasn’t backed by reliable science. So if the D.A. is expected to back off in favour of alternative truths, what chance is there for the rest of us?

We have an ever increasing need for space which puts us into competition with other species; and our aggressive encroachment on natural spaces is disturbing. You can fill your head with passions for esoteric things and there’s no problem: perhaps, forced to read Shakespeare or Dickens at school, you’re no longer sure whether you love or hate just one, or both of them. Fortunately, liking or disliking in your head has nothing to do with the amount of ‘real stuff’ you think you need and the ‘real space’ you need to put it.

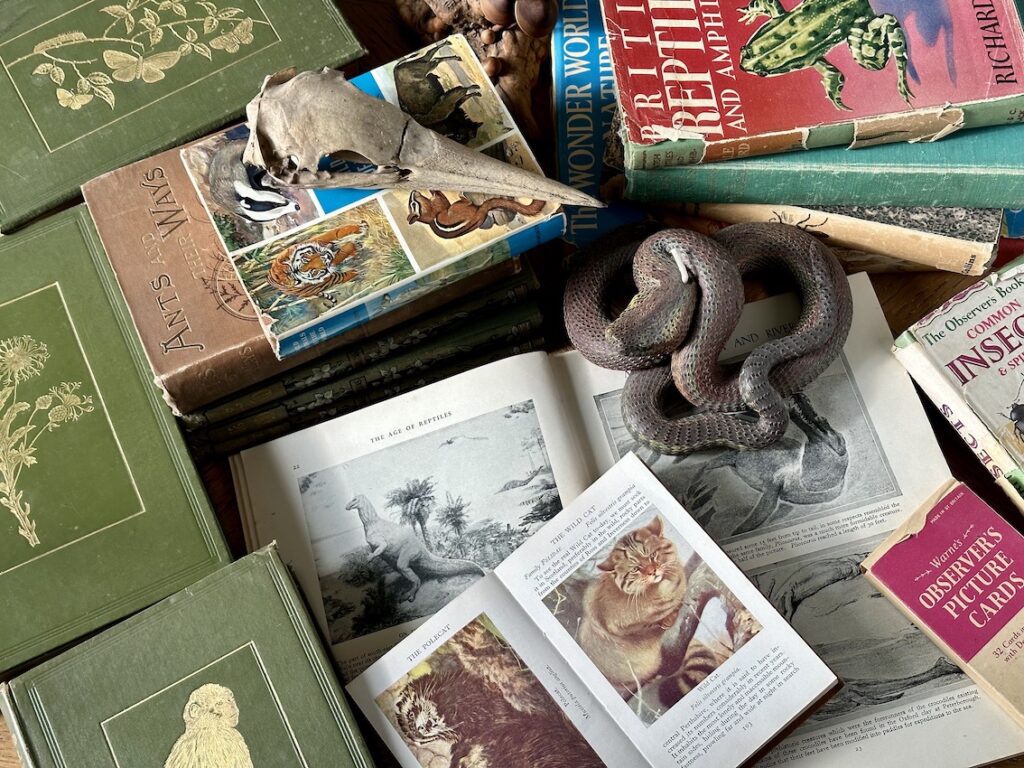

Thinking back to childhood, I’m wondering how much space my ‘interests’ took up. I had my own bedroom, but my ‘stuff’ ran to little more than a synthetic Davy Crockett hat, a pile of comic book Classics Illustrated, and a disproportionate number of natural history books. In retrospect, all of my ‘stuff’ was an escape to worlds I couldn’t experience first hand, although why my priorities eventually moved almost exclusively to natural history I don’t know; but back then my space requirements were minimal. It wasn’t long before I started bringing a few small creatures into my room, although none were of the kind that other children kept. I remember the pleasure of rearing caterpillars and tadpoles — the extreme changes these creatures underwent was a revelation.

Ants would absorb my attention for hours on end. I watched them complete extraordinary tasks as if they were a single organism; it didn’t seem odd that I was the only person I knew keeping ants in a family home. My preference was for creatures with uncomplicated brains, because if I watched them for long enough, I could predict what they might do next. There were molluscs, crustaceans, insects and spiders; along with reptiles and amphibians; and when I was a little older, several creatures that might even kill you. My poor mother — she was very understanding.

When I was small, conservation was in the air. During the 1950s there was an increasing understanding that if things didn’t change, some plants and animals were going to disappear altogether; and behavioural observations along with breeding programmes were about to make the headlines.

In the 1950s Sir Peter Scott had taken endangered Hawaiian geese, bred them in captivity, and returned the offspring to natural habitats in Hawaii.

In 1959 Gerald Durrell opened Jersey Zoo, which later became the headquarters of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Durrell had dedicated himself to saving endangered species and was quick to recognise that public interest was drawn to animals with appeal. Amphibians and reptiles did not feature prominently, but that didn’t stop him initiating breeding programmes for many less charismatic species.

In the 1960s — Przewalski’s horse, extinct in the wild, was captive bred and returned to the Mongolian Steppe; and in the 1970s the Arabian oryx, extinct in its original habitats, was similarly captive bred and successfully reintroduced to a number of desert locations in the 1980s. All of this, was encouraging, and I wanted to get involved — perhaps I could work locally on a much smaller scale.

My ambition then was the breeding of endangered species, although I had no inclination to become a zoo keeper. My pie in the sky dream was to return rare animals to habitats where they had previously existed but were no longer present; but even a child could see the obvious problem with such good intentions: the decline in animal numbers is broadly linked to habitat loss, and once you’d bred your chosen species, where do you release the offspring? The reality of this situation wasn’t peculiar to me, increasingly it was becoming a global issue that many conservationists were forced to consider.

I had started breeding British amphibians and reptiles when I was quite young, initially smooth newts and common lizards, both were common locally. My parents were very understanding, allowing me to build a reptile enclosure in the garden; and then another, and once my cold blooded guests had been provided with appropriate habitat and food, they started reproducing without any help from me. After two or three years, second generation individuals were mature enough to have their own offspring which I released into the local area. This, I felt was an achievement — if nothing else it was a useful learning experience, but as a conservation exercise it was altogether pointless. Clearly, it would be more useful to breed the rarer natives; at the time there were no legal restrictions to doing so and I decided to put all my efforts into increasing the numbers of my favourite, the endangered sand lizard (Lacerta agilis). To do this today, would require appropriate permissions and links to existing conservation projects, if indeed you were allowed to do it at all, but when I was young such concerns were almost non-existent. Indeed, showing an interest in such ‘lowly’ creatures was considered extremely odd.

Sand lizards require a very specific habitat and through the 1970s I regularly visited the lowland sandy heaths where they lived, and quite by accident found myself recording the rapid decline of a species. How sand lizards found their way to these specific habitats in Britain is a puzzle that interests very few people. Sparsely distributed in the U.K. sand lizards exist only in sandy areas where their buried eggs can successfully incubate.

In Europe sand lizards are less restricted in range where a general rise in temperatures during spring and summer allows for a more expansive distribution, especially to the south. One of the few benefits of climate change is that sand lizards in Britain should benefit from warmer summers, but an increase in temperature is a double edged sword, because dry sandy heathlands are destined to burn both deeply and extensively when summers are dry.

Heathlands exist because their nutrient poor soils are unsuitable for most agricultural purposes — why else would they still be there? Traditionally, they are managed by burning and clearance for the purpose of grazing livestock; but making a living from such environments is difficult, and those that have tried usually voice a low opinion of them; but as wildlife habitats sandy heathlands can be spectacular, with numerous species entirely dependent upon them.

In his novel ‘The Return of the Native’ Thomas Hardy, had almost nothing positive to say about Egdon Heath, the fictional ‘furzy briary wilderness’ where his novel was set. Back then, a ‘waste’ was the general term for open heath — although in Hardy’s case, this harsh environment was an allegory for the lives of the people living upon it. Or, it might be that as Hardy’s marriage began to fail, the more miserable his books became. Environments are often used to give novels a sense of mood and place, but the reality is often very different.

As a teenager I learnt about sand lizards by simply watching their behaviour; it was clear that breeding them in captivity would need a slightly different approach to common lizards, as the females of the latter give birth to live young (indicated by their name Lacerta vivipara), although each baby arrives enclosed in an egg sac, from which they quickly break free — I know, because this was the first animal birth I witnessed as a child. Sand lizard females require bare sandy areas to dig and lay eggs in, and there follows a summer of incubation before the offspring emerge.

When young lizards hatched I worked hard to feed them on natural prey gathered in a sweep net; and this continued through early autumn until the youngsters reached their first hibernation. When they emerged in the spring I continued feeding until their release in early summer. This extra work substantially increased the chances of survival to adulthood, although when large numbers of hatchlings emerged, I would release some in the late summer of the first year, because, as the saying doesn’t quite go, ‘you shouldn’t put all your hatchlings in one basket’.

Once back in the wild behaviours didn’t change. On sunny days the youngsters would follow their prey — usually small spiders and insects — up through deep heather, to bask and hunt at the surface, sometimes lying together in twos and threes to gather heat, right through into early autumn.

During the 1970s, the most troubling losses that sand lizards faced was habitat degradation and segmentation. A politician might claim that numerically, more habitats were available once developments had divided them; and this would be true; but any 5 year old considering the singular delight of a birthday cake, would not be fooled if a parent cut up the cake and allowed the adults to eat half of the pieces and then told the child that there were still more pieces of cake to eat than before the cutting began. Across lowland sandy heath a similar division has been going on, which is quite shameful; but unlike most five year olds with their cakes — when it comes to heathland, few adults feel cheated of their birthright.

Back then, segmentation of heathlands was a major environmental issue because unlike dartford warblers, sand lizards cannot fly in from somewhere else when the surrounding segments of heath are devastated by fire. Without links to adjoining habitat, reptiles, without the aid of a significant conservation effort, can be lost forever. The problem is an obvious one, but appreciation has been slow in coming; although efforts are now being made in S.E. Dorset to link important heathlands back up again. There are very few places where such damage can be reversed, and if done successfully, might prove one of the most consequential conservation efforts underway in Britain.

Unmanaged, heathlands quickly revert to scrubland and eventually they progress to forest; despite this, relatively large expanses of sandy heathland survived through until the 1970s, but then suddenly ear-marked for development, this mostly for housing, and especially noticeable on heathland to the west of the New Forest. Easily cleared and compacted, lowland sandy heaths were disappearing at an alarming rate and there was very little opposition — a situation I found depressing.

At the time, adult lizards used in breeding programmes were often rescued from such laces, and I helped The British Herpetological Society (BHS) catch lizards on sites before the developers moved in… and with the clock ticking, we became shockingly efficient at getting the job done.

I lost my first job in television because I refused to reveal sand lizard locations for filming. Over the years I’ve seen articles that provide map references to sites, that allow others to visit and photograph them and I think this unwise — if I along with two or three others could clear a site of adult sand lizards in an afternoon, then collectors working for the illegal pet trade would be able to do the same. Worldwide, many plant and animal species have suffered from the unwanted attentions of collectors, a problem that has plagued the natural world for hundreds of years, but the scale of trading targeted species has become so great, whole ecosystems are now at risk.

During the 1960s when people in Britain were informed that African elephants were under threat, they were greatly concerned, but endangered sand lizards disappearing just a few miles down the road, elicited little response. This seemed odd, comparatively speaking, sand lizard habitat was disappearing more rapidly than elephant habitat, but rational thinking wasn’t helpful. Most people find elephants more appealing than lizards — even the most colourful ones. Conservation organisations will utilse favoured animals to raise money for the broader protection of environments, and if red pandas lived on sandy heaths there would be an outcry every time a heathland was threatened.

When I began releasing young lizards onto viable heathlands, I thought genetically similar animals should be released as close to their site of origin as possible. Moving plants and animals from one place to another without good reason might be considered irresponsible meddling; we humans have done rather a lot of that, sometimes relocating species over great distances, even from one country to another. Much of this has proven undesirable, but when the alternative is a complete loss from a location; or even worse, extinction, arguments against doing so no longer hold.

Adult sand lizards can sometimes appear barrel chested lumberers and not the greatest of climbers, but are they are ‘intelligent’ lizards. When hand fed in captivity they will clamber over the feeder in search of food. I never developed the special relationships that some like to imagine they have with the natural world; I hoped to release all of my captives back onto heathland and needed them to remain ‘wild’. When I showed up at my reptilery, there was usually a lizard tilting its head and regarding me with an angry eye, as if my presence was a minor inconvenience. On occasions when individuals did need to be handled they would bite my finger aggressively and hang on… Sometimes I’d be waiting a couple of minutes for a bad tempered lizard to let me go, so I could return to my natural habitat in front of the television.

During the breeding season when establishing territories, the males would be equally aggressive with one another. Standing parallel to an adversary, each would raise and puff out their bodies to discourage a challenge; if this didn’t work, they would bite and skirmish until one of them gave in and ran away. Individuals that battled for dominance would developed a greater intensity of green colouration, which became much less intense once the mating season was over.

Through the 1970s a handful of people were breeding and releasing sand lizards back on to sites where they had once been, much of this was co-ordinated, but on a small scale. A few concerned people were reacting to a rapidly developing threat to a species on the brink.

Steadily things progressed: Martin Noble of The Forestry Commission became head keeper of ‘the New Forest’ in the mid-1980s and ran a very successful reintroduction programme; while members of the British Herpetological Society had been working efficiently on conservation projects for a very long time. Around 20 years after I started, Marwell Zoo began a large scale breed and release programme monitored by biologists from Southampton University, and running now for more than 30 years.

Sandy heaths do not fare well close to housing developments, they are delicate habitats prone to erosion, with domestic cats and death by fire clearing them of their diversity. In the mid 1970s I filmed a pair of dartford warblers building a nest on a heathland close to a recent housing development. Before the day was out a domestic cat showed up and persistently attempted to catch them. The nest was set low in gorse and the Dartfords had no alternative but to desert. Sand lizards do not have the flying option and are an easy target for cats. Sand lizards have been legally protected since the early 1980s… but in truth, they really haven’t.

If I had a passion when I was a teenager it was probably sand lizards, and without doubt, have found it disturbing to witness their decline. I’ve rescued them from building sites; bred and released them; even made their case on television. “What’s the use of them?” demanded one interviewer. “What’s the use of you?” I responded. Then a BBC producer asked to view sand lizard behaviour that I had filmed at a time when an interest in reptiles wasn’t remotely fashionable — fairly soon, I was filming wildlife sequences.

Passions can lead to many things, but in isolation they are never enough. We can work towards protecting our favourite plants and animals, but if their habitats continue to disappear from under them, we are simply denying the inevitable. My daughter’s observation that people are now being pushed to live in less space is a reality (and will continue as our numbers increase); unfortunately the same is also true for the natural world, and very few species can adapt to the sudden changes. Sand lizards have been pushed to live on small slices of what was once a fairly big cake, and outside of nature reserves, habit loss and trial by fire might well see them off. I haven’t lived in the U.K. for more than 20 years and my association with sand lizards has slipped into the past, but it is encouraging to know that there are others still working hard to conserve this beautiful creature; such efforts are impressive, especially when set against the fact that British wildlife has been in steady decline for a very long time… Sadly, very little is changing.

Dedicated to Keith Corbett who has made a major contribution to sand lizard conservation.