On 6th February 1982 I made my first trip to Haleakala – The Sacred House of the Sun – a dormant volcano on the beautiful island of Maui.

This might sound like a grand adventure, but anybody can do it – all that is necessary is a reliable vehicle and a head for heights, because the journey from sea level to ‘almost’ the top, can be achieved by road within a couple of hours; this may well be the fastest land ascent to 10,000 feet anywhere in the world. Only two things will catch a traveller out, the first is the sudden ear popping change in altitude, and the second – what they will find when they get there.

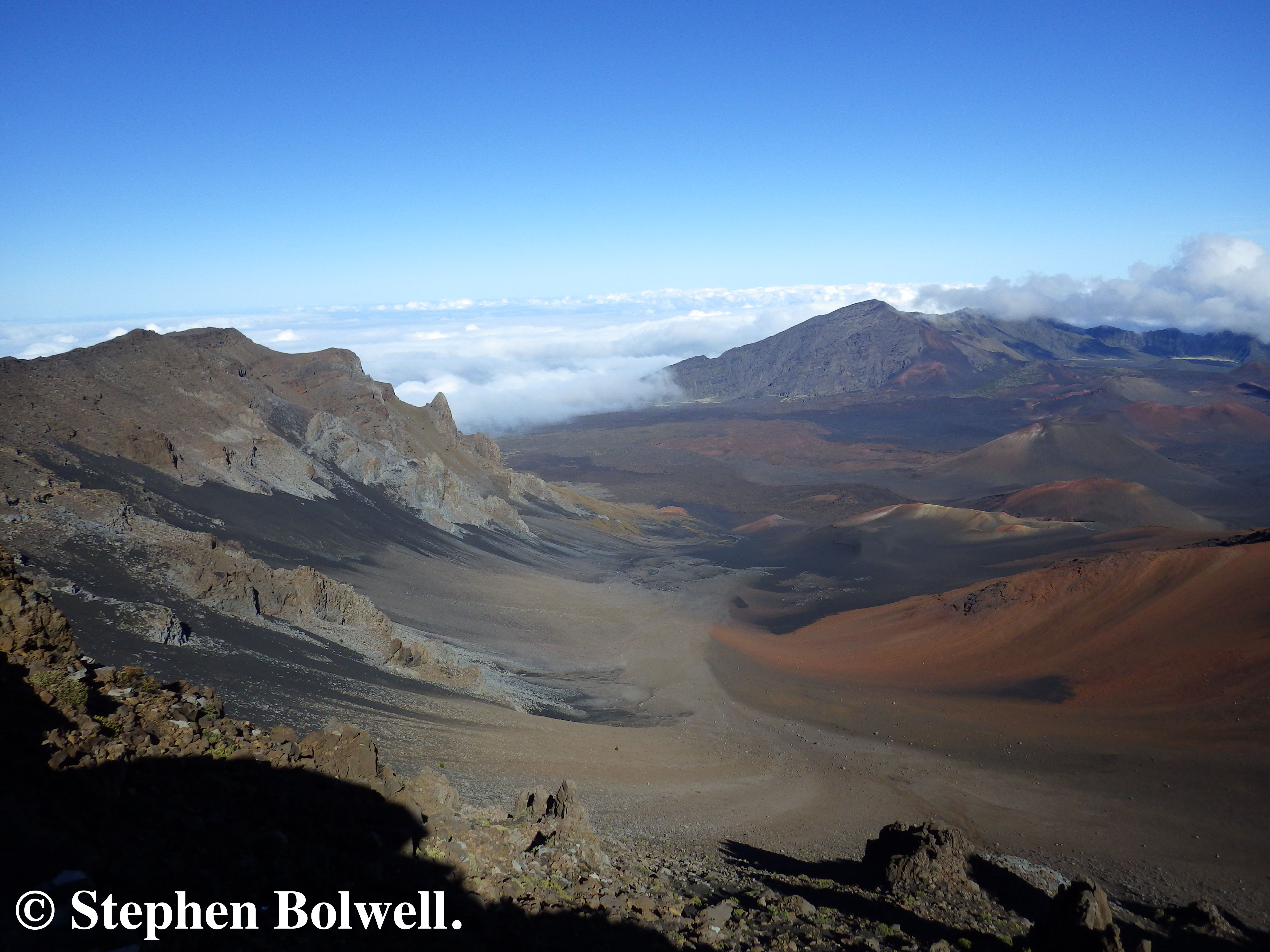

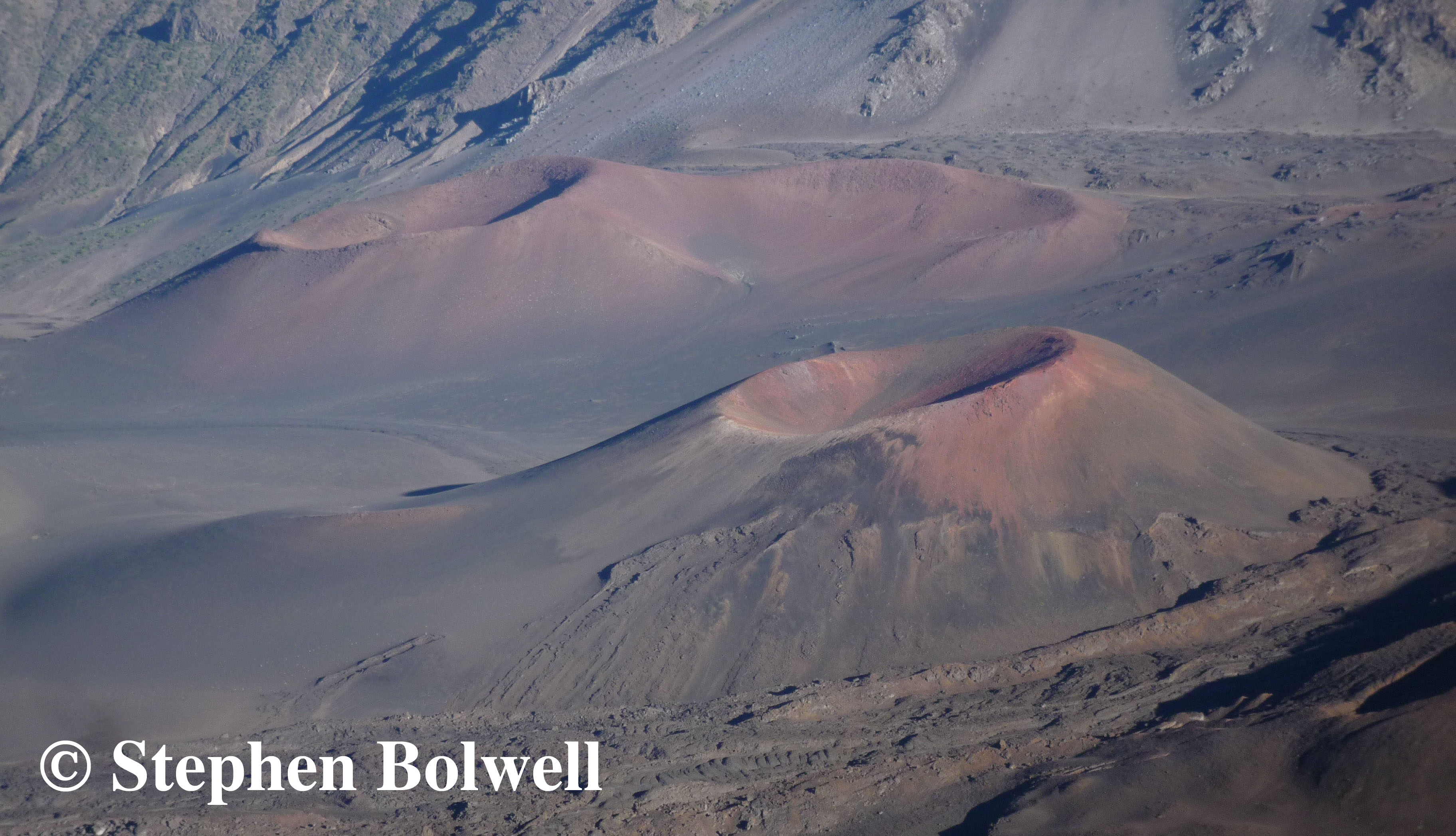

Once up on the lip of the crater, it is difficult to believe that you are still on a tropical island, because the landscape rapidly changes to something quite other worldly. Back in the reality of this planet Haleakala has seen perhaps ten eruptions over the last one thousand years, most recently in the late 1700s and it will certainly go off again at some time in the not too distant future.

This extraordinary environment can be interpreted in two ways – either through mythology, or by engaging science.

To the local Hawaiian people this is a sacred place created by Pele, the goddess of volcanoes who was followed here by her vengeful sister Namaka – a sea goddess. The less spiritual amongst us might question what business a sea goddess has roaming around at the top of a volcano, a place totally out of keeping with her natural habitat. If trouble was likely… which of course it was, then I’d have put my money on Pele – but never bet on what the gods will do, because they move in strange ways beyond the understanding of mere mortals. The outcome was a running battle across the crater floor with Pele finally torn apart by her sibling on the far side to the north east.

The story ends disappointingly for supporters of the volcano goddess, whilst a scientific explanation runs an equally dramatic course now hidden in the depths of time.

Haleakala, like so many places in Hawaii, is unique. Looking across the plug of the crater you might think that you are on another planet rather than standing near the top of the largest dormant volcano on Earth. The crater is 3,000 feet deep, two and a half miles wide, 7 miles long and takes in an area totalling about 19 square miles. Just like the other volcanos in the Hawaiian chain, this one started on the Ocean floor and over the last two million years has risen to around 10,000 feet and perhaps a little higher when erosion is taken into consideration.

Mark Twain described the views from up here as sublime.

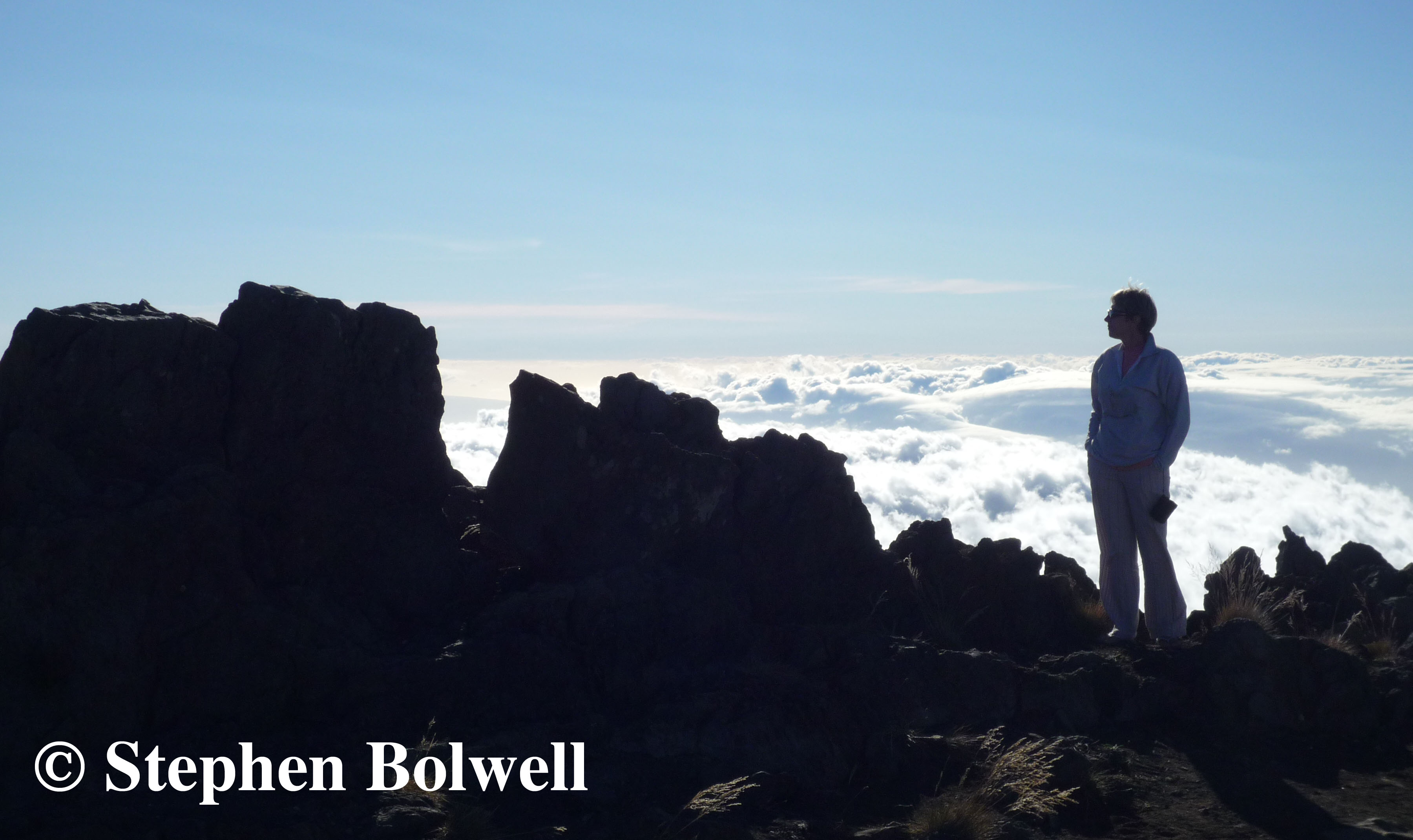

Once above the clouds looking out across the crater floor, it is easy to understand how the mystical legends of Haleakala developed and not at all difficult to accept that a new wave of believers also consider this place intensely spiritual. This is great news because places with spiritual significance are more likely to get protection than those without it. It seems odd that in these more enlightened times conservation can be influenced by faith based belief systems rather than relying entirely upon the facts – but we shouldn’t knock it when worthwhile environments are getting conserved. Mystery excites our imagination, it is how our brains are wired – we are all suckers for a good story with a beginning, a middle and an end. Science on the other hand has the disadvantage of being open ended.

So there was all this interesting stuff to consider on my first day up on the volcano and what was I thinking… that this is Hawaii and I haven’t got a sweater – I’d totally ignored what 10,000 feet above sea level can do to air temperature. I had come to film for the B.B.C. and my producer Roger Jones had made no mention of needing one, probably because he wasn’t my mother and considered that somebody doing my job should at least have a brain… but mine wasn’t working that day; as we climbed I began to see ice and snow by the side of the road and slowly it dawned on me that when I got out of the vehicle I was going to be very cold.

Once you start to climb more steeply, the ascent is rapid; at some point your ears pop, the sky goes grey for a while as you go through the clouds, and on a good day, on the other side it will be sunny with sharp light and deep contrast in the shadows. Up here the air is clean and at night there is no supplementary lighting – perfect conditions for an observatory and it is therefore no surprise to find one.

So what’s the point of going up Haleakala for a wildlife film-maker.

There is presently no discernible life on Mars and this place certainly feels the way we might imagine another planet to be, but with the bonus of at least some oxygen to breathe. Look out across the crater and before you is a rolling bed of cinders for as far as the eye can see.

This place not only has one of the oddest landscapes in the world, it also has one of the oddest plants to be found in Hawaii. The silversword (Ahinaha) manages to survive, by living life in the slow lane and although it can’t move about like a triffid, it can grow to triffid like proportions – a fully grown plant with flowering raceme seems just too big to be living under such inhospitable conditions.

A silversword slowly increases in size growing upwards for well over twenty years and then having put all its energy into a lifetime of super slow development it goes out with with a bang, achieving one mighty glorious mass flowering – then it dies.

So, this is what I came to film all those years ago – one of the world’s rarest plants in flower, in one of the world’s most inhospitable places; and by the end of my first visit I was shivering so much I had to lock the camera off and run it without touching, so that my shot wouldn’t have the jitters. A wonderful opportunity, but all I could think about was getting down from the crater before I became the first person to die of hypothermia on a tropical island.

I’ve been back to the crater several times since, when thankfully it was warm and sunny and I didn’t need my ‘just in case’ sweater although I now never forget it. But here’s the bit that I like best – the one thing that no self respecting photographer will tell anybody… you can film or photograph silverswords from the car park; there aren’t huge numbers of plants, but plenty enough for pictures that will cover various stages of development, and if you can’t get it all done within 50 feet of the car, then you’re really not up to much. The most difficult part is getting low enough to avoid having bits of car or the road in shot … and missing out the tourists is tricky because well over a million visitors make their way up here every year.

I guess when you get to my age and people see you lying motionless on the floor waiting for the background to clear they think that maybe you’ve had a heart attack. The last time I was up Haleakala was a few months ago along with my wife and daughter; and a group of young men began talking about my situation. “Please let me help you up sir”. said one, “Even if you don’t want to be helped up…” Then another “I don’t know if you’re happy just lying there motionless, but please, let us help you up. We really must insist…” This was amusing, but they were far enough away for me to ignore them without seeming impolite – I affected my grumpy persona to avoid conversation and the wasting of time – you never know how long the light will hold. I’ve missed a good many shots with this insular approach… the light has gone, you get back to the parking area and don’t mind a chat. Somebody says, “Did you see that fabulous owl?” And you’re thinking, ‘Owl… what owl?’

The most enjoyable thing for me was the realisation that I have probably seen some of the flowering silverswords when they were just starting out in life and now I was coming back to see them at their end as they burst into flower.

The problem is, that at the time of my first visit I didn’t know that a record of the plants might be useful. Although it had occurred to me when I was younger, that many species were already in trouble, I hadn’t naturally thought ‘take a picture, save the Planet’, and so I didn’t go for a wider reference picture of the car park. This was an oversight as I later had no clear recollection of where plants were, their sizes, or how many. Back then the last thing on my mind was photographing the car park, and consequently I have no evidence to support my feeling that there are now fewer plants growing in this area than there once were.

However, there may be other reasons for thinking there are now fewer plants growing.

2014 was a great year for the silverswords, they managed a mass synchronous flowering. In other years when there were only a few plants in flower it was perhaps easier to notice the smaller individuals coming on, but when large and impressive plants are doing their thing they really grab your attention.

Whatever the case, the silversword is better off now than it has been for some time. Not so long ago goats grazed here, eating anything vegetative they could find including these wonderful plants, but now there is proper control, the silverswords are making a comeback.

Trails exist away from the parking lot where other silverswords may be seen. Beyond the range of the average tourist it is possible to walk and see plants in a more natural setting, although it is important to stay on the trail.

The spiritual nature of Haleakala might also account for the longterm survival of silverswords because until modern times. In the past few people would have come here to simply wander.

Many tribal societies display belief systems that appear to the modern world little more than superstition, but there is often more to appreciate than most of us realise. In the modern world we continually walk in places where perhaps we shouldn’t, destroying the essence of a place by directly damaging fragile ecosystems.

Scientific research is essential to any conservation agenda, but there is another side to the story. Our continual erosive presence in wild places has become a problem: we believe that we have the right to roam wherever we like, often in numbers, with a total disregard to the wishes of local people. But it may be that what most of us regarded as primitive cultures, have belief systems that are more in line with the needs of the environment than our own, especially when they advocate limited access to places that have spiritual significance.

As outsiders we should always tread with care, especially when local people do so for reasons they can’t explain beyond extraordinary tales of the imagination. This way of thinking certainly makes good ecological sense high up on HaleakaIa, as silverswords may be damaged or die if the volcanic cinders around their roots are trampled. In a broad sense the environment here doesn’t look delicate, but in the finer details it is.

Similar myths and legends apply to other beautiful locations around the world. Many of us will visit them to fulfil personal challenges or inner needs. Often we are just tourists looking for fun. For whatever reason, our assumed levels of sophistication have masked our ability to notice the problems we are causing.

One of the great heroes of Polynesian mythology is Maui – his exploits are optimistic and culturally significant on the Island that bares his name.

A story passed down through the generations tells of an evening when the sun set too quickly – this annoyed Maui because the day had passed before all of the chores could be done, and so he hatched a plan. Aided by his brothers Maui would catch the sun in a net when it came up in the morning and refuse to let it go until an agreement had been reached for the sun to move more slowly across the sky. To everybody’s surprise Maui succeeded in his ambitious plan.

And so on a clear day up at the top of Haleakala, it is possible if you stand in the right place, to watch the sun come up and go down without obstruction from foreground hills, mountains or volcanos and in consequence the day becomes longer. But there is more… up here you see a more distant horizon – the sun rises earlier in the east and sets later in the west. Effectively, the higher you go, the longer the day. Polynesian mythology is closely tied to the natural world and local people may have appreciated this, and it makes perfect sense when Polynesian legend claims this place as ‘The Sacred House of the Sun’.

Remember that if you take a picture that might one day help save the planet… tread carefully… even if you don’t know exactly why you should.

For further details of the Tarweed family see:http://waynesword.palomar.edu/ww0903b.htm

For park details on the silversword:

http://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/nature/silversword.htm

Also, ‘Silver Swords in Bloom’:

http://khon2.com/2014/07/30/rare-silverswords-in-bloom-on-haleakala/

With thanks to Dr. Roger Jones for introducing me to Haleakala.